The Best Arguments Against "Persistent Inflation" Have it Wrong

This past week we saw the Fed make a significant change in its predictions about inflation, raising the rate it thinks we will have averaged at the end of a year by another one percent. That means, quite simply, the Fed was wrong about how high inflation would go up to the last meeting, and I am as certain it is still wrong as I was with its previous prediction. More importantly, the Fed shifted from being certain inflation was "transitory" to using a new word in its economic description, acknowledging inflation MAY be "persistent."

Given how completely certain the Fed sounded just a month ago about inflation being transitory and given how the Fed really cannot afford to lose face and risk losing trust, that was a big admission. Trust is all the Fed has to sell. It's proprietary product -- the US dollar -- is backed by nothing other than the public's trust that the Fed will manage the currency well.

The Fed is starting to see what I have been certain of for the past year -- persistent inflation. Even though it is still far short of seeing how high inflation will go, it moved its prediction for the rate and the timing of its first post-COVID interest hikes a lot in just one month's time. Imagine how much more they will move when inflation gets much hotter.

In my last reports, I promised to lay out my numerous reasons for believing inflation is going much higher than the Fed admits and particularly why I see it as being persistent for certain, not just maybe. I'm going to do that in two articles. In this first one, I will counter the arguments that are being made against inflation being persistent.

This time is different

Let me start by working from an article I recently read that does a good job of laying out the reasons the author believes inflation will be "transitory." I want to address why "this time is different" than what the author (and all of us) has seen in the past with inflation.

First I'll let the author set the table for us:

Inflation was considered dead and buried in the US for decades, and many have been wondering what it would take to resuscitate the beast. Well it should come as no surprise that after the largest fiscal spending program in the history of the US, combined with extraordinarily easy monetary policy programs, investors would eventually become concerned about inflation again.

As a staring point, we can all probably agree on that much. Those are the only two inflationary causes most people have seen in years. All of my patrons will know, however, that the key factor is missing here, which is exactly what makes this time entirely different -- shortages.

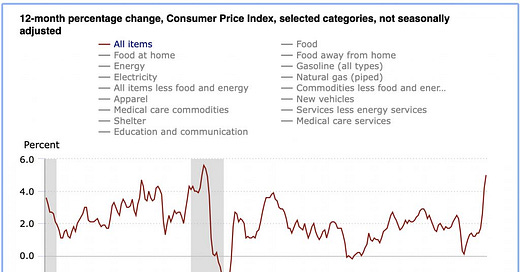

Anxieties have been gradually building since the stimulus programs were first approved a year ago, but there was not yet a lot of evidence of significant inflation. The most recent report on inflation in April, however, showed a 4.2% year-over-year increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the highest rate in over a decade.

Actually, a parade of evidence has been passing in front of us for many months, which I've been laying out here. The author of this piece was looking in the wrong place for initial evidence. Consumer price inflation typically begins with producer price inflation. It starts in production and then works its way up the food chain as producers finally have to pass on higher costs. I have laid out a great deal of evidence on the producer side for coming inflation.

Inflation can, of course, start at the consumer end. A sudden shortage of goods can result in immediately higher prices of those goods, especially as commodities speculators jump in. We see that supply cause in groceries from time to time when meat prices rise because we hear that corn crops are failing, so speculators push up the price of meat before the number of slaughtered cows even falls. What we have now, however, is vastly larger than a single crop failure. The COVIDcrisis and Trump Trade Wars raised the cost for producing inventory for a few years. Because it involves many factors and affects months of inventory build, it won't go away so easily. That inventory has to sell at higher prices to recover those costs, even after the producers' costs stop rising.

The real question investors should be asking themselves is whether the US economy has entered an entirely new regime, one with structurally higher long-term inflation ahead.

Indeed, so in both of my articles I'll focus on that question, which the author says is most important in figuring out if this inflation will prove to be sticky and outlive the Fed's welcome (for right now, the Fed has been welcoming inflation -- saying it wants higher inflation to balance the long period of low inflation we came out of, though it already says inflation is going higher than it intended or expected. (I have never fully bought into the Fed's argument, though, that it wants higher inflation for awhile. I think it knows its continued easing is inevitably going to create some, so it has been laying the groundwork to keep people from getting too concerned about it when they see it happening. Only problem is that it is coming in much hotter than the Fed expected. The didn't expect it rise so easily because the Fed has not been able to get inflation up to 2%, but now it has the help of shortages, which are going to be part of the economy's "new regime" for longer than the Fed can convince people inflation is not a problem.

In the months ahead, we expect nearly every inflation indicator to report higher prices than consumers and business owners are accustomed to.

On that much we fully agree, but consider how even this person who is arguing inflation is going to be "transitory" does not sound like it's going to pass this summer. The Fed, as I noted in may last article, thinks we'll close the year with an average for the year that is less than what inflation has been running the last two months. If this author is right about several more months at even higher prices, the Fed's projection of 3% annual inflation will be impossible. If we see rising inflation for several months, as this author argues, that will clearly put the year well above the Fed's new 3% prediction!

Yet, we also expect these above-trend price increases to be relatively short-lived, reflecting a variety of factors, including: easy year-over-year comparisons, which are based off an extreme time period a year ago that will eventually fade....

This is the Fed's fantasy narrative that says a good part of the rise in prices is due to a "base effect." Nearly all economists readily joined the Fed in claiming the latest high inflation rate was due to the "base effect." The base effect was a mere three-month dip that became part of the basis for saying the inflation will be transitory. There was, however, no month of negative YoY CPI rates back in 2020, other than in a few individual products, but no drop in the overall CPI average. While the CPI index rate (which measures the difference from one year to the next), as shown on the graph below, did not go up much from April through June last year, it didn't go negative either:

You can see the last time prices went down enough to leave us crawling out of an actual hole was ever so minimally back in 2015, and no one back then was saying the next year's inflation was not as high the government's numbers claimed because 2015 had touched below zero. The only place you can see prices were crawling up out of pit was after the Great Recession. The present argument is nonsense because the dip was nothing but a reduction in the rate of rise.

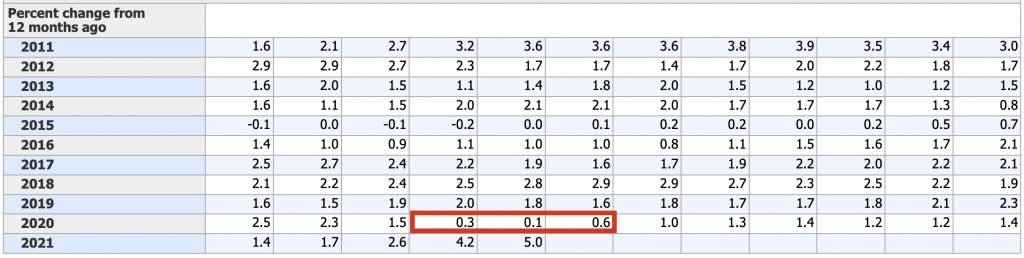

Here are the historic inflation rates from the BLS charts quoted for CPI with the "dip" months in 2020 circled:

That's not a dip. It just isn't much of a lift.

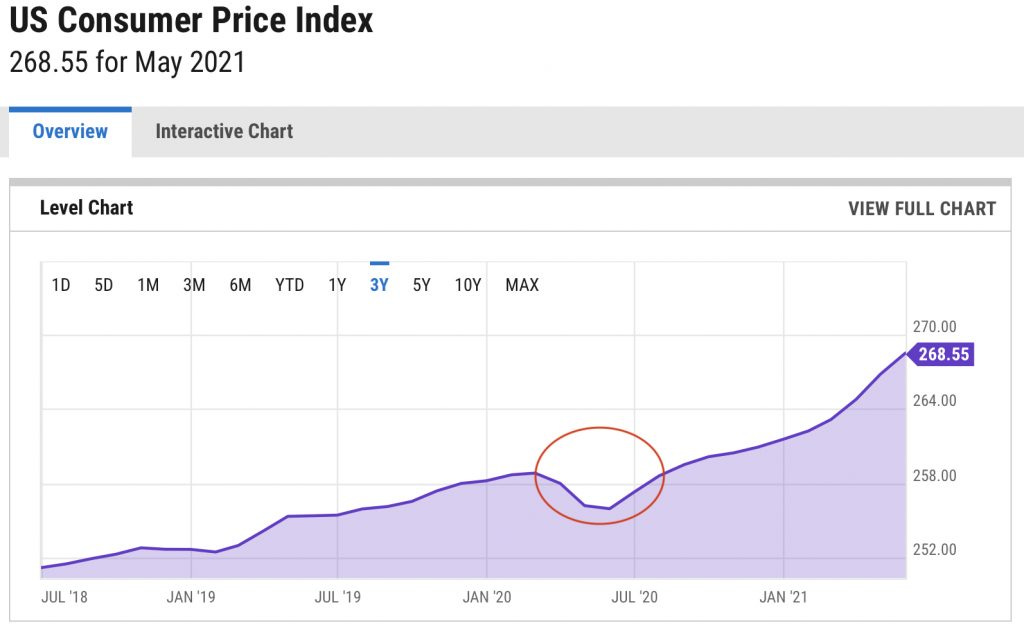

Let's look at inflation another way where you can see a dip of sorts:

When inflation is viewed in terms of the aggregate of prices monitored for the CPI, there was a dip. This number, however, is the average of prices measured against the average of for prices back in 1984 when CPI first began to be tracked. The true base year, 1984 (not 2020), is set at "100," so a measure of 268 is 168 points above the 100 base line, or a rise of 168% since 1984. So, in this graph you can see the dip talked about, but that is in aggregate prices as measured against 1984.

On the one hand, you might say "fair enough" to all those who claim the 4.9% increase over a year ago is off the bottom of that dip, not off where we were just before we fell into the dip. However, let's put that suddenly popular argument into perspective:

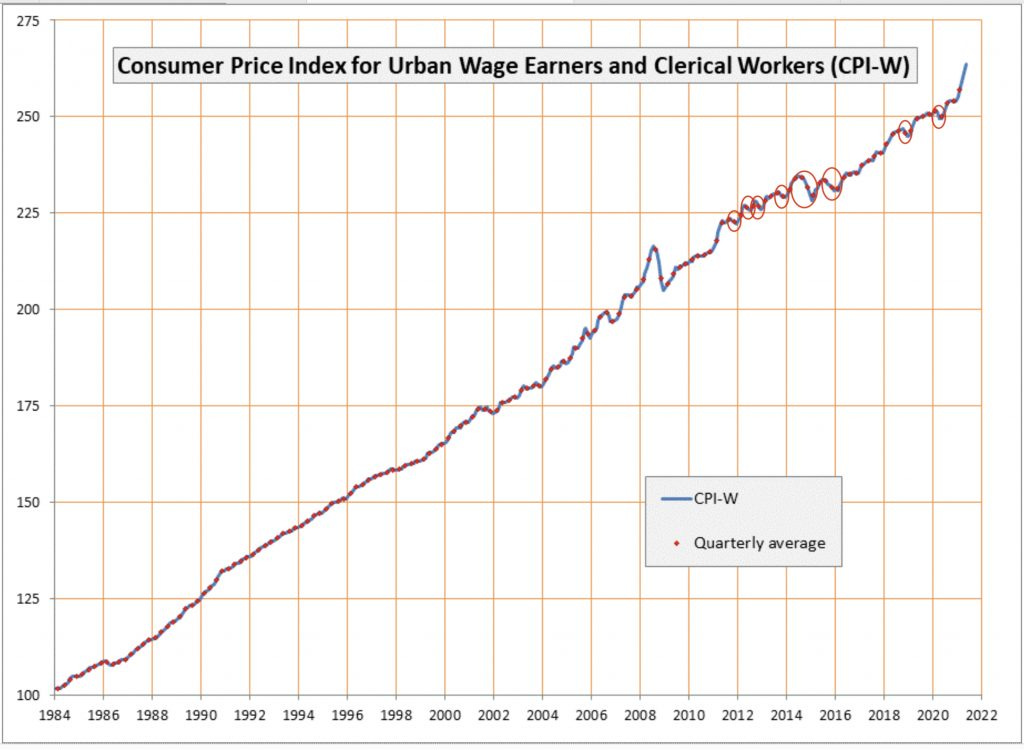

As you can see by the numerous circles I placed on the graph after the big crash of 2008-2009, there have been many dips in this aggregate price comparison to 1984 since the Great Recession, some of them two or three times as large as the one in 2020, and NO ONE claimed the next year's CPI percentage increase didn't fully count because there had been a dip the year before! This is the first time we are repeatedly hearing that rationale because 1) the Fed doesn't want us to worry that inflation is as bad as it is right now, so it's reaching for an argument it has never used; 2) the Fed did want us to believe it was coming close to its 2.0% increase each year in all previous years, which is why it never used this argument for all the dips along the way prior to now; and 3) no one else really wants to believe inflation is as bad as it is either. I call that "denial."

What I see as significant when I look at that graph above is not the almost invisible dip in early 2020, but the incredibly sharp rise ever since. Note that the only other time inflation rose as steeply as it has been rising in the past twelve months for as long as it has been rising during those COVID months was immediately before our global crash into the highly deflationary Great Recession. So, this kind of inflation may be "transitory" in the sense that it it will quickly transit us into a major deflationary crash, but that is precisely what I've been claiming -- not that inflation will keep rising like this for years to come, but that it will rise until it breaks us.

In all things economic, there is rarely a straight line to anything, especially over a number of years. All upward trends have their dips and all downward trends have their blips; and the 2020 dip looks insignificant compared to other blips along the trail that we never talked about at all. So, can we stop talking about the nonsensical baseline affect that we have never talked about before?

The author then lists other factors that will make today's inflation "transitory," meaning just an anomaly related to reopening, not a transition into another catastrophic, deflationary economic collapse like we saw in '08 and '09:

... a rise in commodity prices from artificial pandemic lows and their bullwhip effect on supply chains (e.g., lumber and semiconductors); and a surge in demand in select areas, including hotels, airlines, used cars, car rentals, etc., as the economy reopens.

O.K. But what basis is there for believing any of those inflationary factors are going away soon enough to help the Fed out of its trap? They may be surges, but "bullwhip effects on supply chains" can cause (and I'd argue are likely to cause) damage that is fairly challenging to fix. I argue that supply chains have been whip-sawed for several years now due to trade wars and then COVID factory shutdowns and COVID border shutdowns. As a result, they are riddled with years of damage that won't correct in a few months.

Supply-chain problems are not, in other words, just in "transition" (transitory effect) through a brief surge due to reopening. You know, "trouble keeping up." We have a lot of supply-chain linkage to repair. The economy in terms of its supply chains has entered an entirely new regime where businesses are trying to rebuild more robust supply chains than what we had (as in more diverse, so not as dependent on trade with just China). In many cases, that means building new factories or expanding existing ones. Those factories and their shipping infrastructure take 2-3 years to build.

The author argues against that as follows:

Businesses weighed the trade-off between cost efficiency and supply chain reliability, with the former mostly winning.... Companies shipped many of their most labor-intensive jobs offshore and adopted the practice of ‘just in time’ inventory management to further cut back on costs. These savings offered relief against pricing pressures for both businesses and consumers. The global nature of the pandemic, combined with the ongoing risks of intellectual property theft, shipping bottlenecks, and geopolitical tensions, have businesses reconsidering their decision. We haven’t seen much in the way of action at this point, so it remains to be seen whether a ‘reshoring’ of jobs and changes in supply chain or inventory management will actually occur. Moreover, continued advances in technology, particularly in the areas of robotics, automation, and artificial intelligence, should help alleviate any increased costs that might otherwise be incurred with this effort.

I agree that we don't know to what extent it will happen, but even the advances in technology will initially require increased costs before they bring labor savings down the road. It will take time to build the factories that build the labor-saving robots, and how about those chips??? Seems to me, robots need chips -- the very thing the supply chains seem to have left many manufacturers short on. So, while we don't know how far businesses will go with this, we do know their answer to the problem will take time and will raise costs during that time. Any savings is well down the road. Therefore, if by "transitory," we mean that inflation due to supply-chain changes will end in 3-5 years, that could be, but the Fed doesn't have 3-5 years to ignore inflation. For the next several years, this change is an additional expense and is considerable.

Additionally, recent headlines about labor shortages in the hospitality, leisure, and restaurant sectors, among others, are leading to higher starting wages and benefits.

Sure, but those increases in costs are the very ones that are certain to last far into the future. You don't easily strip wages or benefits back down once you've raised them. That's why companies much prefer "hiring bonuses" to wage or benefit increases. The fact that many are giving wage and benefit increases, says the hiring bonuses are not cutting it.

Even if labor rates stopped rising right now, the part of year-on-year inflation that is due to wages will keep running hot over all the months that are comparing back to months prior to the wage increases, keeping that measure of YoY change at a sustained higher level for a year, at least. And I am certain there are many months of additional wage increases to come.

Labor remains the predominant cost for most businesses.... The relatively higher percentage of unionized workers in the 1970s created a self-reinforcing cycle between contractual pay increases tied to cost of living increases. This flywheel effect doesn’t exist to nearly the same extent in today’s labor market.

At the same time, labor did not have the advantage of being on general strike around the globe back in the 70's for an entire year while government paid labor more than they had been making when they were working! Now the extra pay from that past year has been saved or invested, and labor can run off of it longer in holding out for higher wages even after government support ends ... IF it ends. We have seen government forbearance programs on rent and mortgages, which hugely aided labor, extended several times. So, we don't know for certain that all the unemployment augmentation will end in September, as scheduled either. That can has also been kicked down the road more than once, too.

Effectively, guaranteed basic income has boosted labor's strength during a global general strike more than any labor unions were ever able to do with their isolated strikes. That effect will build, at least, through September. That much is certain, and it may be extended longer. (I anticipate providing more perspective on the labor subject in my next article.)

We can’t discuss the inflationary period of the 1970s without acknowledging the price of oil as a major contributing factor. At the time, the US had recently become a net importer of oil as declining domestic output could no longer keep pace with increasing domestic demand.... While not quite fully self-reliant when it comes to crude oil, the US has since become a net exporter of energy, as recently as 2019, for the first time in nearly 70 years, while OPEC’s influence on global oil markets has steadily eroded.

The period of the 1970s could be described as a supply shock.

I think the 2020's may prove to be a period of even worse supply shock in oil than the 70's but for different reasons. So, I disagree with the author on this. Under the Biden administration, Big Oil does not have a favorable environment for exploration and development, and Big Oil's capital expenditures even during the Trump administration were way down. The same is true in Europe.

So, as demand rises again under re-opening, Big Oil's ability to fill the demand has decreased. Emphasis in the energy business is moving to technologies perceived as eco-friendly, and without a doubt those technologies are more expensive than oil because they require more development. You can count on the Biden administration to force the energy industry to become greener because that is what his constituents want.

From $35 per barrel to $130 per barrel—this is the range for oil prices in the next few years that we could see, according to a commodity trading group.... One thing that can hardly be disputed is that lower spending on exploration would inevitably lead to lower production. This is what we have seen: the pandemic forced virtually everyone in the oil industry to slash their spending plans. This is what normally happens during the trough phase of an industry cycle.

What doesn't normally happen in a usual cycle is long-term planning for smaller output. Yet this is the response of Big Oil to the push to go green. Most supermajors are planning changes that would effectively reduce their production of oil and gas. In Shell's ... case, it has been literally ordered by a Dutch court to shrink its production of oil and gas.

So, it's pretty clear that supply is tightening, and oil prices are reflecting this. In fact, supply has lately shrunk so much that even the International Energy Agency, which earlier this year called for a suspension of all new oil and gas exploration, is now calling for more supply....

According to Castleton's Reed, the recovery in oil prices was only to be expected. In that, he is the latest in the growing choir of voices predicting higher prices, even north of $100 per barrel, before too long.... It is a little harder to see oil falling to $35 a barrel unless a lot more supply is added. This would be a perfectly realistic scenario in any other cycle. Now, producers both in OPEC and outside it are wary of the energy transition and its expected effect on their business, and are not in a rush to boost production.

My statement for 2021 has been that numerous supply shocks (not just in oil) will create high inflation. This is as certain as the oil supply shock in the 70's. With domestic oil production also struggling against the Biden administration's greener goals, I would not count on low-priced oil.

In our view, the main risks to our inflation outlook sit squarely with the policymakers, both fiscal and monetary, with fiscal policy being the most impactful. As business activity and consumer spending returns to life, the concern is whether government leaders intend to keep their foot on the gas, pumping further stimulus into an already rapidly heating economy. Historically, this answer would be no, but new polling evidence suggests that recent spending proposals are quite popular, perhaps so much so that political leaders may feel supported or even encouraged to ramp government spending.

Absolutely. Not only are they popular and, therefore, hard to remove, but the new government is made up of many "progressives" who have been arguing for several years for modern-monetary theory to be implemented and for universal basic income. Now that the COVIDcrisis enabled them to achieve those goals almost effortlessly (as in without even any serious congressional or public debate), they will fight hard to avoid retreating now that they are in the ascendancy after years of feeling sidelined. The Great Economic Experiment has begun, and those who have risen to power have another year-and-a-half to further their goals. If they survive the next election, they have two more years, at least, after that. The Bernies, Warrens, AOCs, etc. aren't going away now that their positions are, as even this author admits, "popular." It will take high inflation to prove their ideas don't work and knock them down.

Putting bond baloney to bed

You have probably heard Chairman Powells' infamous quote when he was on the FOMC back in 2012, near the beginning of the end of economics as we once knew it:

Why stop [monetary expansion] at $4 trillion? The market in most cases will cheer us for doing more. It will never be enough for the market. Our models will always tell us that we are helping the economy, and I will probably always feel that those benefits are overestimated. And we will be able to tell ourselves that market function is not impaired and that inflation expectations are under control. What is to stop us?

One of the arguments some have thrown up against my inflation articles as they have appeared on other sights is that bond interest does not support my claim that inflation will rise much hotter. I'll counter that with the help of an article by Nicholas Colas of Datatrek, who questions the proverbial wisdom that says the long-term bond market is great at predicting where inflation is going and pricing interest accordingly. Colas asks, "What If Everyone Is Wrong About US Inflation's Impact On Interest Rates?"

While high inflation was not a widely shared concern among stock investors a little more than a year ago in April when I started writing in these Patron Posts that inflation was likely, at last, to come in hot and hard (see "MMT is Here! Start Stacking Money Like Firewood," Colas now writes, and many would, I think, agree,

I (Nick) have never seen a stronger consensus around a macroeconomic topic in my +30-year career in finance. Fed money printing plus fiscal stimulus/debt issuance plus economic reopening is supposed to equal high and likely lasting inflation.

Colas goes on to say, however, of people like me who think inflation will rip the market to shreds,

When the market doesn’t go in the direction you expect while all the headlines are in your favor (and, boy are they ever…), you have to stop and reassess your point of view. There is nothing wrong with being wrong. Continuing to stay wrong when the market says you’re wrong is, however, not a great idea.

My problem, however, is not that the stock and bond markets aren't going my way even though nearly everyone agrees inflation is here. The problem is that nearly everyone is trusting that the Fed knows what it is talking about when it says this rapid inflation that is filling the headlines will be merely temporary. That is inspite of the fact that the Fed just coughed up a hairball and admitted it may not have been right about that after all. The biggest problem, however, is one that Colas will demonstrate: Inflation at a consumer level has only just arrived, and longterm bond yields are actually more reflexive than accurately predictive. They respond to the inflation that was and that is. As to what lies ahead, bond investors are not omniscient.

Inflation has months to go in which to finish its work on both bonds and stocks, and there is much evidence in my opinion that it will. You cannot expect inflation to arrive and instantly kill market sentiment because, by definition, inflation does its corrosive work over time, and bond investors have no better crystal ball than stock investors. A look at the history of bonds and inflation will prove that point.

I said clear back in that April, 2020, post that inflation would take its time in building before it does any damage to markets:

If you've read here long, you know I have not been one to write arguments fearing hyperinflation ever on this blog. (And we have not had any in all that time, except in assets where I said we'd see inflation....) We're in a generally very disinflationary environment. So, that buys the Fed room for now and time for you to keep an eye on inflationary pressures.

Well, now you see those pressures in plain sight. Prior to now, I've been pointing out how they were building behind the scenes on the producer side. So, don't expect the market to crash in a day now that inflation has broken through the surface on the consumer side. This is going to be a battle between the bulls and the bears. What I've said is that inflation will win for the bears.

So, let's deal with the permabulls' main argument against any market consequences from inflation, which is that bonds are not showing much belief in inflation so far; so, there won't be much inflation.

Colas asks,

So, what is really going on with Treasuries? Our answer is that this is a much more of a “show me†market than many investors may realize. It takes its lead from long-run historical precedent, not present-day data. Consider this graph of 10-year Treasury yields (black solid line) and CPI headline inflation (red dotted line) from 1962 to the present:

This graph shows me quite plainly (beyond argument really) that bonds are not particularly forward looking! What I see is that inflation has sometimes peaked and bonds didn't respond much at all. (See the mid seventies). Then I see the ten-year rate has sometimes even peaked a year or two after inflation peaked. (See the early 1980s that everyone compares to the present.) Bond interest has sometimes been reluctant to follow inflation down, not really trusting how low inflation was going. (See the two decades in the middle of graph.) Then there are times when it did ever so slightly anticipation inflation and also fall a little before inflation. (See just before 2000.) Right now (at the end of the graph), we can see inflation, as measured by CPI has just begun to rise steeply, and bond yields have started to rise synchronously with it. There is nothing on the graph that would make me surprised that 10-year bond yields are not fully trusting and joining inflation's current moves.

So, I am not inclined to make as much about the predictive ability of the bond market using the ten-year for a gauge as many do. I'd say the belief that long-term bonds are predictive is a fable. Look back at 1970 when bonds and inflation peaked simultaneously, but the move up in bonds started after the move up in inflation.

In point of fact, the 10-year yield reveals itself historically to have had almost no predictive ability at all. It looks largely responsive and even a bit hesitant to track with inflation. There is, therefore, no sound basis for claiming now that, because long-term bond interest seems hesitant to rise, inflation won't be much of a problem. It's fabulous nonsense. Today may prove to be much like the mid-seventies where the rise in bond interest was slow and steady while inflation blasted off like a rocket, and where bond interest didn't peak until, at least, a year after inflation peaked.

This graph, in my opinion, puts that argument to bed for good. People are just believing what they've heard in their economics classes without thinking about it or checking the argument out against historic facts. They have the theories they've learned, and they are sticking to them in spite of no evidentiary support to the theory. Says Colas,

The lesson here, which seems to be playing out right now, is that 10-year Treasuries anchor their inflation expectations around long-run trends rather than any year or two of CPI reports.

I would argue even further: At best they match up to inflation, but often with a lag.

Powell on the howl

In critiquing the most cogent arguments against persistent inflation, I don't want to skip over Fed Chair Jerome Powell. So, let me parse his prepared comments about inflation for congress today:

Inflation has increased notably in recent months. This reflects, in part, the very low readings from early in the pandemic falling out of the calculation ...

There is that base-line argument again. As pointed out above, the dip was much less significant than some other dips in the past decade; yet, the Fed never argued that inflation was actually lower than the headline CPI number back when the Fed couldn't get the headline number up to 2.0%. Why? That would mean the Fed was falling even further from reaching its 2% goal; but now it pulls that argument out routinely because its desperately trying to convince people this isn't all that bad.

... the pass-through of past increases in oil prices to consumer energy prices ...

As just noted above, OilPrice.com says oil COULD go as low as $30 a barrel, but they say a great deal more about how companies are structuring their plans for the future around green initiatives. So, $100+ oil is a more likely bet. When the Fed is basing its policies on blue-sky scenarios for Big Oil in a time where nations are pushing to go green, they show themselves, again, to be desperate for an argument. I think oil's price rise is far from "past."

... the rebound in spending as the economy continues to reopen ...

The Fed could be right about the demand side (spending) being a surge. If anything is likely to be transitory, it is the rebound in demand. Rapidly rising prices have one self-correcting mechanism. They squelch demand as people adopt more conservative buying habits. A new rise in COVID cases could also suppress demand, but that is less likely now that a good part of the population has been vaccinated (so long as the vaccines don't prove to have their own broad health risks).

Is the rebound in demand just a surge or something that will continue? I don't know. The Fed, however, should be betting it will continue. That was, after all, the plan. Still, it's not unreasonable for them to think there may be an extra-large surge of pent-up demand right now.

and the exacerbating factor of supply bottlenecks, which have limited how quickly production in some sectors can respond in the near term. As these transitory supply effects abate, inflation is expected to drop back toward our longer-run goal.

On that point, however, they are betting on a perfect dream when they are likely to get a perfect storm, but I'm going to give a more detailed look at the bottlenecks in my next Patron Post.

That's it. That's the Fed's best argument in a nutshell for inflation still being "transitory" where to my view, only one point in four holds water.

Commodity prices falling ... or not

Finally, another argument used by those who want to deny the inflation narrative, is that commodity prices are falling again, so inflation must be over. So, let's take a real look at that via the one commodity thought to be most prognostic. Copper, called "Dr. Copper" because its rise and fall in price is often considered diagnostic and predictive of the economy's rise and fall in health, started falling again lately. Those who want to believe inflation is only transitory, say, "See, copper has now put in a top."

That is far from an established fact. As with the aforementioned CPI dip that was of no significance when compared to other dips in the past decade, history will teach the lesson here, too. You can quickly snapshot the validity of the argument by looking at the graph below and noting that copper prices (bright aqua line) have put in the same "top" several times since the start of the COVIDcrisis in 2020, and each time, copper has climbed even higher right after ... well ... just a little bit longer than how long it has been falling recently: (The blue and green lines show key copper inventories, not prices.)

With almost precise regularity, copper has hit a plateau (sometimes just leveling off, sometimes peaking above the plateau then settling down to it) five times since it started rising. Each time it has subsequently climbed again the same amount it has climbed just before its latest plateau. It only becomes a top when copper finally stops taking the next stair-step up, and nothing in the current price action looks any different than the last plateau before it took another step up. So, there is no way to say this was the top step.

More importantly, copper in the last twelve months has gone up about 66% in cost. Even if it falls by half of that, it will still be up by 33% for the year, which is massive inflation. It can, in other words, fall a great deal from today's nosebleed heights and still end with annual inflation that is extreme, and then it can make another 33% rise all over again next year.

It's already been in a falling wedge pattern and broke out to new highs. There is no reason it cannot do it again. There is simply no basis for knowing based on price action whether copper is done rising or whether it will climb yet another step and end the year up 100%, which would in my way of thinking be hyperinflation.

Much the same can be said for lumber, which has lost about a third of what it gained. Both copper and lumber could stop halfway down from their outlandish rise, and still be additive to overall inflation for months to come because they'd still have much higher inflation values than most items that are being tracked, thereby continuing to pull the average inflation of all measured prices up to their higher center of gravity.

Now that I've countered the arguments that are being made against inflation being persistent, my next Patron Post will lay out arguments for why it will be persistent.