Flying Upside Down over Wonderland in a Cold-Air Balloon about to Burst: Welcome to Negative Interest in Bond Bubbleland

The US debt ceiling is likely about to be lifted. When it is, it will release a deluge of government debt issuance that has backed up for four months. That could cause a temporary spike in bond yields as so much debt rushes out to find buyers. That has sometimes happened at such junctures in the past, but not always.

Whether that shock risks breaking the bond bubble, or inflates it is complicated to figure out. So, I'm struggling with it.

On the one hand, with the Fed now promising to lower interest rates that are already low by historic standards, many are asking if the US will wind up taking interest below the zero bound as Europe has done and what that will mean. On the other hand, recent government auctions have already gone poorly, foreign financiers appear to be running away, and the government is going to double down on its debt issuance shortly in that environment right as the Fed starts lowering it's target short term rate, even as it continues rolling off government bonds, which should be pressuring government bond interest upward.

To get a picture of this strange environment, think of the bond bubble as a large balloon floating through the darkening sky. Since the value of existing bonds in bond funds inflates (prices people will pay for bonds rise) as interest on bonds (or yields) fall, think of that falling interest environment those bonds travel through as the atmosphere around balloon. As the atmosphere gets thinner (declining interest) the higher the ballon rises, the balloon also stretches and inflates (price value of bonds rises). If the atmosphere goes negative (the balloon moves into the vacuum of space), the bubble super-inflates.

The question, then, is does it burst, or can it hold together in a vacuum? Can the balloon (a huge bubble) just go on inflating for as many years as interest continues to move beyond the zero-atmosphere bound, and can interest ever return to earth from that upside-down unreality without killing the passenger who have ridden along it that gondola? Do you keep riding the gondola even as you are increasingly running out of air to breath or jump out and take your chances with falling back into richer atmosphere with real earth far below?

That's a strange odyssey far outside of my experience (and most people's in the US) that I'm going to explore a little in thought, even as I worry a bit about the temporary effect that lifting the lid on the government debt may have next week on government bond interest rates, given the critical juncture at which it will be happening.

Feel free to help me out in comments because I don't profess to be an expert guide in Wonderland.

Right now our balloon is up against the US debt ceiling

Congress established the debt ceiling in the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917. It was a restriction put in place when the US government authorized the treasury to issue long-term bonds to fund World War I. Rather than going to congress and the president for every issue, the treasure would be allowed to expand debt to a certain limit set by congress.

Prior to that, treasury debt had been shorter-term bills, or it took out specific loans, such as the Panama Canal loan. The intent was to cap how far the treasury could go with its long-term, wartime bond issuance without getting further congressional approval.

Short-term bills were not intended for long-term debt in the way they are currently endlessly rolled over and increased in number. They were a way for the government to get through immediate shortfalls until more tax revenue came in. Longer-term government bonds, when they were created in 1917 to fund the war effort were, however, intended to accumulate longterm debt during the war period (with the idea that they would be paid off after we made it through the war).

The debt ceiling is a limit that Congress imposes on how much debt the federal government can carry at any given time. When the ceiling is reached, the U.S. Treasury Department cannot issue any more Treasury bills, bonds, or notes. It can only pay bills as it receives tax revenues. If the revenue isn't enough, the Treasury Secretary must choose between paying federal employee salaries, Social Security benefits, or the interest on the national debt.

The nation's debt limit is similar to the limit your credit card company places on your spending. But there's one significant difference. Congress is in charge of both its spending and the debt limit. It already knows how much it will add to the debt when it approves each year's budget deficit. When it refuses to increase the debt limit, it's saying it wants to spend but not pay its bills. That's like your credit card company allowing you to spend above its limit and then refusing to pay the stores for your purchases.

Congress imposes the debt ceiling on the statutory debt limit. That's the outstanding debt in U.S. Treasury notes after adjustments.

The adjustments include old debt. The debt that is, thereby, capped is "public debt," which is the debt government owes to other parties outside the government. The capped debt does not include debt the government owes to itself, such as to the Social Security Trust Fund and Medicare.

The debt ceiling has devolved into being a last-resort way for the minority party to get the attention of the other in negotiating the total government budget. They can threaten to hold the US government hostage.

The debt ceiling was last suspended until March 1, 2019, when it went back into effect. Since then, the government has issued no new debt via treasury bills, notes or bonds. The only treasuries issued since March have been for the sake of rolling over existing debt.

Plotting course as we fly into space and through a wormhole or through a rabbit hole into Wonderland

When I make my predictions, which have so far been pretty accurate, I rely completely on fundamentals and not so much current market fundamentals (such as earnings) but major economic fundamentals and the Fed's actions because you don't want to bet against the people who have unlimited money-creation ability and who are the ones who have been filling all balloons now flying with hot air that, in recent times, they have been allowing to cool.

That is why, in 2018, when the Fed was destroying money and raising rates (sucking air out of the balloon and cooling the air that was left), I bet on the stock market facing serious difficulties in its flight dynamics. My predictions for when things would happen was based on the Fed's published schedule for diminishing money supply to a market that had risen to astronomical height purely on the Fed's hot air that had been floating stock and bond balloons ever more aloft for a decade. Since the Fed scheduled a lot of its tightening months in advance, it was easy to know when the ride would get bumpy and lose altitude.

Lots of free money or lots of taking away free money does move markets quickly in either direction, though many believed the fantasy that what goes up never has to come down. While the Feds actions effect markets quickly, they effect the economy very slowly, so my prediction this year of economic recession are based on the lag time for the Fed's tightening and the fact that tightening (deflation of balloon-sized bubbles) has continued in the form of the Fed taking down its balance sheet, even as it kept interest rates steady. Markets can respond in immediate anticipation before the Fed's inflationary money is even created based purely on the Fed's promised moves.

The economy, on the other hand, responds as the money slowly gets loaned out and spent through and respent (velocity of money) and as money from gains in the markets sometimes seeps out into the economy (not much seepage trickling down, though) or even as losses erode spending. Not many of the inflationary effects on the general economy happened because most of the money has been respent within stock and bond markets. So, all the inflation has happened in those assets and in housing prices were low interest rates were intended to stimulate purchases back to their pre-crash levels. (Foolishly because those levels already proved unsustainable without endless low interest and loose credit to support those prices.) That means, I figured, those assets would get hit the worst during the Fed's deflationary period of tightening.

However, it all eventually impacts the economy.

But lets come back to bonds.

That said, sucking money out of the bond market as the Fed has been doing should make a big difference in the bond market. (Since a lot of that money crosses over to stocks, it makes a big difference there, too.) Most of the money the Fed was sucking out of the system was from government bonds. That forces the government to issue more bonds on the open market in order to refinance the debt the Fed stops backstopping with its own indirect purchases.

However, for the past few months we have not been seeing that difference in the bond market because the government right now has been on a debt hiatus, unable to issue any new debt but just rolling old debt over because of the politically frozen debt ceiling. So, bond yields have remained low, rather than rising as they were when the Fed started tightening (and as they theoretically should). Since March, the government has been doing the now-common pay-our-bills-by-borrowing-from-Social-Security-and-other-funds nonsense that congress prefers.

What will happen soon (likely next week since the house has already approved it and gone home so it has now moved to the senate) is that the purely political cap on the debt ceiling will get lifted, and the government will suddenly be able to repay all those IOUs to other funds by issuing new debt, inflating our bond balloon once again. Then we'll see the government debt soar once again. That, however, should send interest on bonds back up, increasing the yield pressure around our balloon, because itincreases supply on the market at a time when we demand for recent government bond issues is already falling.

(Sidenote: If bond yields go up, that will also tend to suck money out of the stock market by making the yields on bonds look more attractive, and the stock market has already stalled out at its own ceiling, which it has pressed ever-so-slightly higher every half year or so for the last year and a half. So, stocks may be no safer place than bonds at the time when bond yields go up ... if they do.)

EVENTUALLY, all of that will play through the economy because so much interest is also influenced by government bonds. So, rising bond yields will also tend to tighten the economy a little more when it is already showing signs of stress from overtightening and trade tensions.

One thing I couldn't factor in to my prediction of a summer recession, which was based on the lag time for all of the Fed tightening that happened in 2018, was any knowledge of when our mercurial congress would lift the debt ceiling. Keeping the lid clamped down because of party politics could delay the recession because it is artificially stalls these anticipated moves in bond interest and in all the interest rates built off of government bond interest.

On the other hand, that means the bond market may swing very quickly upward in yield (down in price/value) when the lid is lifted and the government suddenly plays catch-up. We saw that happen during the Obama administration when Republicans, who had been keeping the lid clamped down on the treasury for four months since December of 2012, raised the debt ceiling in May of 2013. Suddenly government debt issuance skyrocketed and so, coincidentally, did bond yields. Over the course of about two months yields on the 10yr treasury shot up one full percentage point and continued to rise more slowly for the remainder of the year. (The government, of course, does not try to recover all ground lost in its bank account instantly, or it would pay even higher interest.)

Likewise, rates climbed for almost a year after the debt ceiling was raised in September of 2017. On the other hand, they fell long and hard when the debt ceiling was raised in 2011. So, there is no clear reading on the impact of lifting the debt ceiling on bond yields because so many other factors also affect what happens to bond interest, such as (as noted above) what the Fed is doing at the same time and what is happening with inflation.

The point is, all of this WILL play through and affect yields and everything else to some degree because the US federal debt will suddenly balloon as the government issues new debt in order to pay off the IOUs it has written to social security and other departments to keep paying its bills. This will create a surge in the supply of government bonds on the market. However, there is more than one force in play because the Fed is moving in the opposite direction in terms of effect by returning to a path of easing (if it does as it has essentially now promised it will do). The belief that more quantitative easing (Fed bond buying) is about to come may play more in the mind of bondsmen than the Fed's lowering of interest rates next week. Congress hopes to approve the raise of the debt ceiling that same week.

Another risk here is that the Fed has not been able to measure the full effects of the tightening it has already done over the last few months because of that lid on the government's side of the Fed's quantitative tightening scheme. It's rolled off debt at full speed, but the government hasn't refinanced that debt, though it soon will. That means the Fed may be later in putting some slack back into the system than it realizes because its sight glass was clouded by the government's stall. So, the Fed's minor loosening action this month may have little beneficial effect coming as it does against the government's major raising of the debt ceiling without any cap for two years ... if the senate approves that bill as it is thought the senate will do.

(Of course, the Fed's recovery, as I've noted for years, could never actually bear any real tightening anyway because it is all based on markets that the Fed has made dependent on its own largesse.)

A dangerously implosive situation may have built up because of how the debt-ceiling lid times out with the Fed trying to measure its effects of having switched from a monetary loosening regime to a tightening regime and now contemplating a move back to loosening. They are making their moves based on monitoring a politically clogged system. The results could catch a lot of people by surprise (maybe not in a day or two but in fairly short time) as market corrections that have that shock capacity many have been talking about could finally start to move again.

Be ready for a jolt

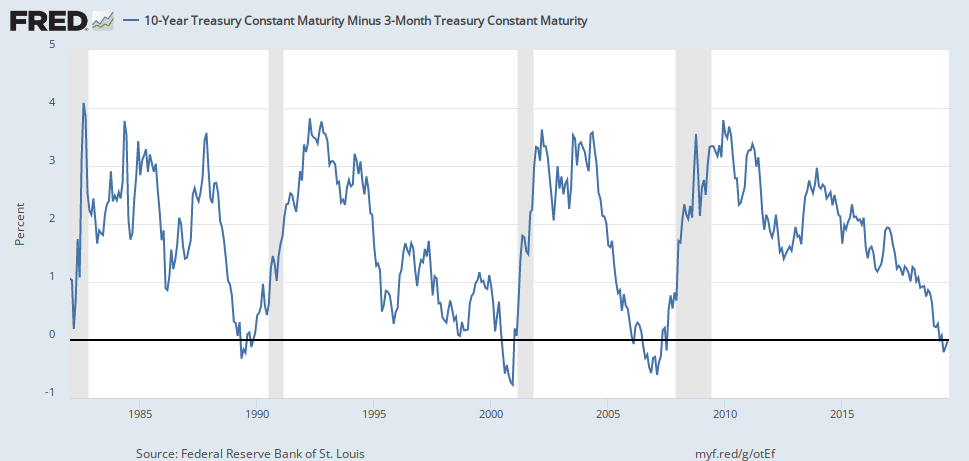

When the artifice of a government cap is removed from government debt issuance, the yield curve may likely steepen (depending on whether the government chooses to issue most of its new debt as long-term bonds or short-term notes and bills); but that steepening will hurtle us into recession (or deeper in if we are already in) by suddenly raising interest rates at those bond maturity dates where the government chooses to issue bonds, even as the Fed moves back into lowering interest rates as the short end of the curve.

Don't think for a moment that the steepening of the yield curve after a few months of inversion is some kind of relief. It is the worst news. Recessions always begin shortly after the yield curve reverts to positive -- sometimes immediately after and, at most, nine months after. That reversion happened this month. With the Fed taking down short-term rates as the government likely sends up longterm rates, the yield curve could steepen sharply.

Moreover, now that the Fed has already rolled many of bonds off its balance sheet at the long end of the curve, it has already tightened that end of the curve. Only it doesn't know how much it has tightened that end (nor do we) because of the jam-up that has prevented the government from refinancing that debt at that end of the curve.

At the same time, the Fed's decrease in its short-term rates tends to increase inflation, and perceived increases in inflation also drive up the yields on longer-term bonds. If bond yields do jolt upward because of this combination of reasons, the bond market is particularly fragile and dangerous right now.

If the debt limit doesn't get raised before the senate goes into its August recess (not likely), it will not happen until September, leaving very little time between raising the limits and government default now that the government has done about as much internal borrowing as it can according to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, meaning the situation will be much more perilous if it doesn't happen now:

Estimates from the Treasury Department and the Congressional Budget Office have put the deadline for raising the debt limit, required for the U.S. to continue to be able to pay for all government services and benefits, sometime in the latter half of 2019, likely by early October ... after which there could be another partial government shutdown if lawmakers and the White House can’t agree on appropriations levels.

But the Bipartisan Policy Center, which tracks federal inflows and outlays carefully, said Monday the true “X date†could be moved up to early September given softer projections of corporate tax receipts. That was injecting a greater sense of urgency into the discussions....

“I would hope that we would never think about default. We have not defaulted on our debt, to my understanding, since 1812,†Senate Appropriations Chairman Richard C. Shelby, R-Ala., said Tuesday. “If we have the thought of default or going right up to the brink of default, it sends shock waves through the financial markets of the world. We, the Congress and the administration, owe the American people a lot better than that.â€

I don't think there is much risk of actual default, but it doesn't take default to throw yields into the stratosphere. Recall that the government's first credit downgrade came because a credit agency merely perceived the risk of default was growing. If senate Republicans do play brinksmanship games using the debt ceiling as their keep-away ball, this is a particularly critical time to be doing that. While it is not likely they will try that again, after what happened once already with the United States' credit rating, it is a potential risk factor that is large enough that could send yields up and crash the bond bubble. So, that risk is at play during the week ahead, too.

Here is where the treasury account balance is right now:

The treasury will want to get back up to that peak balance as soon as it can, given the huge deficits the government is now running. (Cash cushions don't last long in this environment.) As noted, recent auctions, limited as they have been, have already struggled to find buyers due to concern about the impending debt ceiling. So, the treasury is going to have to walk a careful line in how fast it gets its bank account at the Fed back up to snuff.

The treasury will have until after the next election to issue bonds without hitting the ceiling again if the bill that passed the house passes the senate. So, they will pace things out, as much as they can to avoid a funding crisis by hitting the market with a deluge of supply; but, still, they have a lot of ground to recover; they have IOUs to repay and employees to keep paid, even as the deficit seems to continue its rapid rate of expansion.

And here is what tends to happen to another kind of spread between government treasury bills that mature before the ceiling is raised and those that mature after it is raised during the countdown to the day when it is lifted (the critical days of the countdown -- as shown in the graph below -- that we'll be in this coming week):

The more the congressional decisions gets down to the wire as to when the money runs out (such as it did in 2013), the more some rates rise.

The weird and whacky world of balloons

Here is an example today of the delirious thinking that almost no one in the financial media questions. It typifies the kind of unclear thinking that is guiding our many big balloons in flight. My reason for writing this blog, as stated from day one, was that the financial media just parrots the nonsense that brokers, analysts and economists feed to them without questioning (much less trashing it as they should). Today, I felt lightheaded, myself, from the oxygen deprive atmosphere this analyst was breathing before writing:

“Earnings have been quite good. Its no surprise that they have beaten estimates, as they have for all but a handful of the 100 plus earnings season I’ve analyzed,†wrote Ed Keon, chief investment strategist at QMA, a quantitative equity arm of PGIM. “But the beats so far have been about 5%, and it looks like growth will be about 2%, much better than the losses forecast before the season started. It’s clearly been a tail wind for stock prices.â€

These people need to stop sucking in their own balloon helium if they are going to speak without sounding like Donald Duck. Earnings have barely been beating estimates, and estimates were already lowered into the basement and then jack-hammered through the basement floor! So, earnings are not good, much less "quite good;" they are merely better than the dismal recessionary levels that were promised, and they are not enough better to escape an earnings recession, as I've read other writers saying this week. As I noted in a post of my own this week, earnings that are actually in, when meshed with FactSet projection for the earnings that have not yet come in, still average more than 2% NEGATIVE. That IS an earnings recession since they were negative last quarter, too.

As dense as these guys are, I don't know how they fly so high. Moreover, earnings are maintaining this "beat" over dismal expectations only due to stock buybacks, not due to an improving business cycle or increased revenue. Revenue has been largely down! Earnings are measured per share, and the number of shares is taken down by buybacks. Buybacks also create artificial demand that drives the price of shares up.

Airheads like this are not going to guide a market successfully through the downdrafts that are now forming around us. In assessing this helium-headed enthusiasm, bear in mind how everyone thought new market highs each of the previous three times the market got up into the present stratosphere were breakthroughs. Here we are again, and the market gurus are as oxygen deprived as ever. That is how bullheadedness works. It keeps believing it can charge forward and break through. "This time will be different." But why would it be when economically so much is worse (auto sales, manufacturing, housing sales, etc.), trade tariffs are assailing businesses, business revenues are declining, forward guidance is falling, and earnings are only floating at all due to buybacks and are, then, only better than much lowered expectations?

You have to ask, "What would change all of that?"

Is a trade deal going to be struck this summer? You can believe that if you want, but, again, everyone has been bullheadedly believing that misguidance for over a year now, and they haven't been right yet. I see no evidence that the sides are any closer to resolving their actual differences. I see only evidence that they are talking as a way to keep tariffs from going higher because even Trump doesn't really want higher tariffs now that he sees how they damage the US economy and his pet stock market.

I don't know about you, but I make my investment decisions based on evidence, not based on hopes. However, if you're a high flier, then I suppose you will make your risk decisions based on what you believe the rest of the market is hoping and is going to continue to hope because that is what determines where the market goes. Just remember, reality always prevails eventually; so you'd better have a parachute and be ready to jump quickly if that's the risk you choose to take because the balloon you are riding may deflate quickly.

Are corporate revenues going to go up? Based on what? Earnings could go up because earnings can be created artificially with buybacks from stockpiled cash from past revenues, but companies will be less inclined to borrow if the Fed's rate reduction is small or if it is ineffective in taking down long-term interest since it focuses exclusively on the very short-term side of the interest spectrum. (The Fed's bond buying was intended to drop longer-term rates, but that is still in reverse unless they stop their unwind ahead of schedule at this July meeting.)

Is business going to get better so long as the trade war is on? I don't know when that cash from repatriated past profits will run low, but I still think the support of buybacks will start to diminish the year. I don't like to invest my retirement funds based on best-case, priced-to-perfection scenarios; but everyone has their own risk comfort levels as well as their own timelines for recovery if their decision plays out poorly.

This whacky wonderworld of bubble-headed thinking gets even weirder, and herein lies my greatest concern about what is now happening because I suspect bubbles distort into peculiar shapes right before they implode or explode.

From a historical perspective, the bond market is currently acting a lot weirder than the stock market. The U.S. stock market looks like it often does at this point in the business cycle, which is not great for the probable range of forward S&P 500 (SPY) returns, but bonds are doing things they haven’t done ever before in history, which should give investors pause.

There is more than $13 trillion worth of negative-yielding bonds in the world now, including many long-duration bonds:

Rather than getting paid interest in exchange for owning a bond, these bondholders are paying for the privilege of lending money to their governments. More specifically, rather than actually paying a negative rate, they are paying money upfront in exchange for a promise of less money in the future, like buying a $100 bond for $101. The effective yield to maturity is negative.

Yet, Wonderbond World gets weirder still. Consider this recent article about Denmark where negative bond rates have gone the lowest for longest:

"Bankers Stunned as Negative Rates Sweep Across Danish Mortgages"

At the biggest mortgage bank in the world’s largest covered-bond market, a banker took a few steps away from his desk this week to make sure his eyes weren’t deceiving him. As mortgage-bond refinancing auctions came to a close in Denmark, it was clear that homeowners in the country were about to get negative interest rates on their loans for all maturities through to five years.... Denmark has had negative rates longer than any other country.... The ultra-low rate environment has dragged down the entire Danish yield curve, with households in the country paying as little as 1% to borrow for 30 years....

Yes, negative mortgages! And, in spite of this Alice-in-Wonderland world where people with adjustable-rate mortgages are now being paid by the banks for borrowing from them, inflation in Denmark has remained stuck around 1% for five years while real incomes have been rising! This is the kind of inside-out stuff that happens when you go through the rabbit hole below the zero bound and into the upside-down world of negative interest rates. And what's not too like? Danish homeowners are feeling rich right now! No wonder Denmark is rated as the country where people are the happiest in the world. They get paid to buy houses!

Also getting wildly whackier: even those European nations with higher debt-to-GDP ratios than they had a few years ago when their bond yields exploded into the stratosphere are now seeing their bond interest continue to drop (even lower than US bond interest)! That should be good news for US government bond yields that are still in Right-Side-Up World, right? If the rest of the world is dying to pay to give their governments money (I guess because they're so rich from their banks paying them interest to take out mortgages), that money should flee to the US where it could make real interest, allowing the US to also pay lower interest.

The other weird thing is ... that isn't happening! US government bond interest has pushed up incrementally in the past month because foreign investors would apparently rather pay their governments to take their money than loan it to the US for more money. Even though US 10-year yields are low by historical standards, they are the highest among G-7 nations right now, even though the US economy is marginally more sound.

Would you lock money away for a century in Austrian bonds at 1%? Or in 30-year Germany bonds at 0.3%? Or in Italy for 50 years at 2.8% when they had a sovereign debt crisis seven years ago at lower debt levels than they have today?

Some of this may be mandated by various government regulations, forcing money to stay in countries, requiring certain kinds of bonds as collateral for other activities, institutions being pressed to buy their own nation's bonds in order to support those nations, etc. So, I don't know if its a melt-up, but I do know it is an historic anomaly on an historically massive scale.

So, what do we do? Where do we go? Where ARE we going?

I haven't actually figured out yet how to make sense of all of this. I just wanted to make clear to my readers how much is up in the air this week and in the weeks ahead. Maybe we can make better sense of it together. Such, I suppose is the expected nature of crossing over into Wonderland.

That is why the writer quoted above says the bond market right now is getting spooky. Something weird is happening. Major forces are colliding in opposite directions. As we all know, the global bond bubble is the biggest baddest balloon of all bubbles, and when big, bad, balloonish bubbles start to show deformities on their surface, that might be the time to get concerned about being in that market and bail out before riding into the storm that is blowing those irregularities into the bubbles' sides.

Of course major shifts could mean major gains. In a way, the ripples on the surface appear positive. With rates about to move toward negative, money in bond funds that already hold higher-rate bonds should be secure; but the movements are odd, and we haven't seen a bond bubble of this massive national and global scale ever pop to know what that even looks like. Are we seeing the equivalent of a stock-market melt-up happening in Europoean bonds with all their crazy euphoria while US bond funds show some sign of blowing up the old fashioned-way by just just seeing bond prices deflate (which happens when yields rise) to where the funds will become illiquid as investors want to escape falling prices? Since low yields mean high prices, maybe people are running toward negative-yield European bonds because they mean extremely high bond prices, and investors are betting that is a never-ending world because banks are trapped within it -- a speculative market that will take those bond prices past the moon. (Classic melt-up scenario, only in bonds rather than stocks, which always ends catastrophically if you're in the last round of investors caught in that Ponzi updraft.)

Of course, if the US stock market crashes first, that will drive money into government bonds and will tend to bring bond yields down, so there is always that caveat in a situation that is building toward the Everything Crash. One has to try to guess which chunk of the macro picture is going to collapse first. Right now the bond bubble is looking bizarre, and the stock market very toppy and choppy for a year and a half.

I think I'm going to jump back out for the time being, until I see which way this thing turns and have a better sense of what is driving the extreme abnormalities.

We also have the Fed's bond roll-off coming to a halt in September, unless they decide to move that date closer in time, and that should ease the upward pressures on bond yields in September, but the government's ceiling cap is likely to be lifted right away. So, until the Fed stops tightening via its roll-off and returns to quantitative easing (as it is most likely to do whether it wants to or not), I'm thinking of jumping out of bond funds. I don't like massive bubbles with contorting surfaces. Just hope I'm picking the right time to jump.

(Everyone might benefit from everyone else's feedback at this possibly critical and complicated juncture, myself included.)

![Joe Ross from Lansing, Michigan [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons Joe Ross from Lansing, Michigan [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!v0OI!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb2f2ba87-08cb-4136-b711-25bbf41fb89a_885x950.jpeg)

![By Neuroxic (Own work) [CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons By Neuroxic (Own work) [CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!NiQx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F79fcc961-4f55-4c52-9266-a1602f64323c_300x286.jpeg)

![Édouard Riou [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Édouard Riou [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iXUk!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2f0ecb94-b2a4-43e4-8897-2a4ce66c861c_710x988.jpeg)