COVID Brings New Hope to First-Time Home Buyers

When dinosaurs went extinct, mammals gained opportunity to flourish. Crises for some bring opportunity for others who can adapt to benefit from new environments. I try to enable my readers to position themselves to be the ones who will come out better at the end of this crisis.

Future calamity has already been set in place by our response to the coronavirus; so you cannot stop the crisis from hurting humanity, but you can still try to position yourself to be one of the new mammals.

(For this analysis, we don't need to debate whether the economic response to COVID-19 was too severe or not strict for long enough. It already happened. The damage is real, and the damage is deep, whether necessary or not. So, this article is about dealing with the new economic environment we have already forced upon ourselves by our response, whether rightly or wrongly.)

For first-time home-buyers or those who were planning to move in a year or two, selling now and holding out for the end of the decline could yield rewards. I am not certain of a price decline, but I think it is more likely than not, and this article is about how to position yourself for that as well as about the caveats that may keep that from happening.

If you are happy to remain right where you are, you should stay with the home you love; but if you're looking at downsizing for retirement in another year of two, you may want to consider selling now and renting for a time. Likewise, if you're someone who has been priced out of the market, hope may be on the horizon. No assurances, but here are many factors you should consider about the market's present rise and what is likely to come months from now.

The Housing Market Meltup

The first thing to bear in mind right now is that the housing market, like the stock market, is rising in the calm space between two storms. Reopening released a flood of pent-up demand and a bunch of sellers hoping to catch that demand during the normally hot-selling months for real estate. Interest rates have never been lower. The unemployed are almost all being carried along by the government, as are their mortgages or rent payments by government-mandated forbearance. So, the ability to buys is still strong. It's a sweet spot that won't stay sweet long.

As I laid out in a recent article, this surreal summer is seeing an unseasonable chill start to set in on its economic statistics already. (See "Drumbeats of the Epocalypse: The Economic Death March Has Come to Town!") August promises much worse as a month of rainless summer heat storms (economically speaking), leading into a highly tumultuous fall election season.

So, now may be a time to sell and hold, rather than buy and hold; but there are important caveats to watch out for.

Privately-owned housing starts in June were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1,186,000. This is 17.3 percent (±11.0 percent) above the revised May estimate of 1,011,000, but is 4.0 percent (±9.1 percent)* below the June 2019 rate of 1,235,000.

It's normal for June to rise above May for home construction. And, after a cooling-off period due to the shutdown, one would expect a burst of pent-up activity upon legal reopening of the economy. To be down 4%, year on year, during the month of reopening, however, indicates the housing market has sustained some damage. (And notice the high unreliability of the numbers in the present unusual environment, evidenced by how much they may be off plus-or-minus.)

In most of the country, the already tight inventory of houses for sale dropped considerably during the shutdown. It would appear that some owners didn't want people who might have COVID parading through their homes and coughing on everything. Others didn't want to sell into a market nearly devoid of buyers who also didn't want to parade through homes of people who might have COVID.

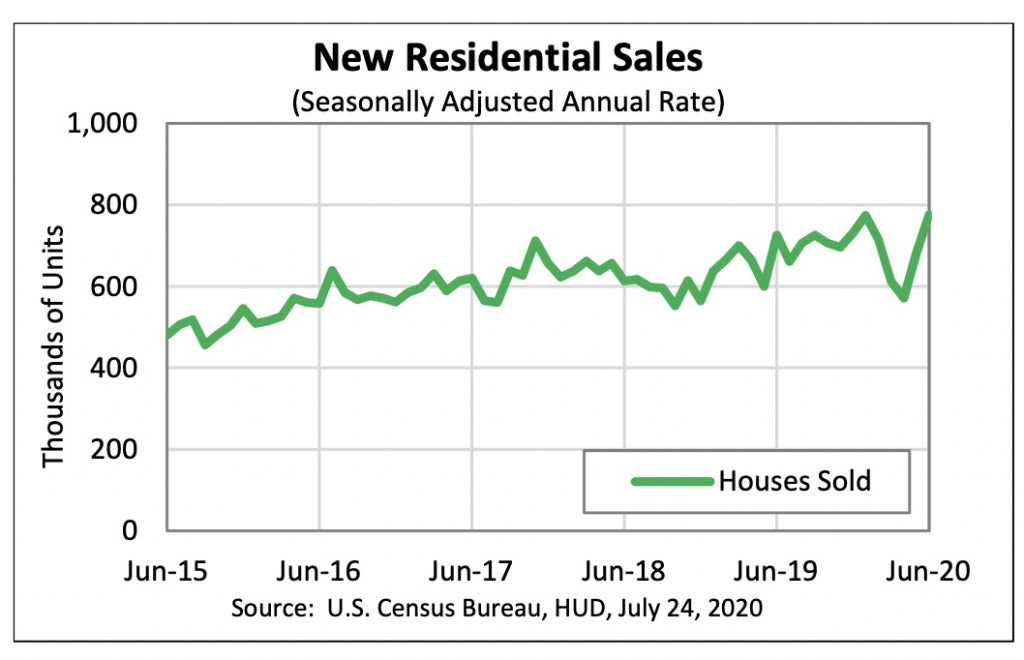

Reopening loosened that back up, and builders apparently feel enticed to build and people enticed to hire them. Some statistics are even better. New housing sales have shot right back up to their last high of recent years:

Sales of new single-family houses in June 2020 were ... 13.8 percent (±17.8 percent) above the revised May rate [which] is 6.9 percent (±13.7 percent) ... above the June 2019 estimate.

Reopening seems to have loosened up buyers more than sellers. In some places, like San Francisco, inventory shot through the roof, but buyers present a more reluctant picture.

San Francisco is now flooded with homes for sale. "Active listings" surged to 1,344 homes in the week ended July 5, up 65% from the same week last year, and the highest number since the housing bust amid a 145% year-over-year surge in "new listings...." This is "pent-up supply" coming on the market at the wrong time of the year when supply normally declines (chart via Redfin):

What that article is saying is that supply usually floods the market, as do buyers in June, then both take a lull during July, and then rise again in late August/September as people seek to close deals before school begins. SF's supply in June shot up considerably beyond the normal rise for June.

What that looks like to me, more than recovery of pent up supply, is like people are heading out town! They are listing their homes in droves in order to get away from the big city. Many real-estate analysts agree, and this time I'm content to go with the reasoning of the majority because it makes a lot of common sense and fits what I hear on the street as well.

The effects of the economic shutdown were severe:

Pending sales had collapsed 77% by early April compared to the same time last year, but then started digging out of that trough. In early July, pending sales were still down 8% from last year and now are following the seasonal downtrend and appear to be back on track, just slightly lower.

In other words, sales did not fully recover. Even with the surge, sales are still down YoY in SF by 8%, even as supply has skyrocketed. The seasonal downtrend referenced is that tendency for real-estate sales to cool off briefly in July, only to rise again in late August.

Since the rise in SF sales is significantly less than data graphed above for listings, that is bound to put downward pressure on prices for those seeking to make their exodus from the big city.

A lot of new inventory flooding the SF market is likely to hurt SF prices when people want to get out of Dodge because they don't like their COVID survival odds. People want greener pastures -- literally -- not densely populated urban environments where they can't do anything anyway. So, demand is not going to match up to inventory.

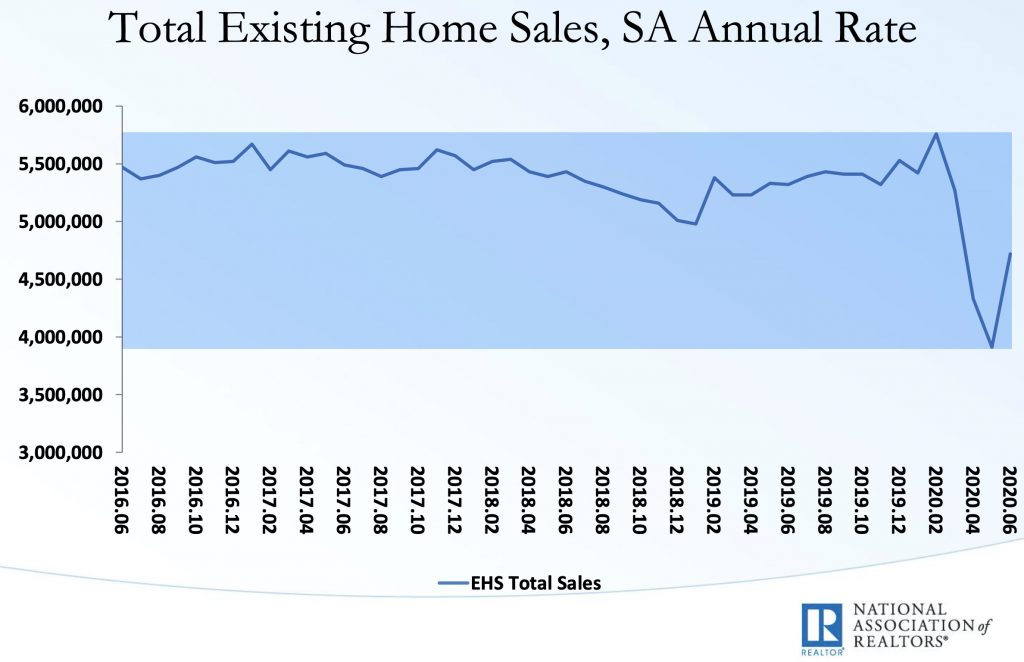

Nationwide the picture for sales looked like this by the end of the June reopening period:

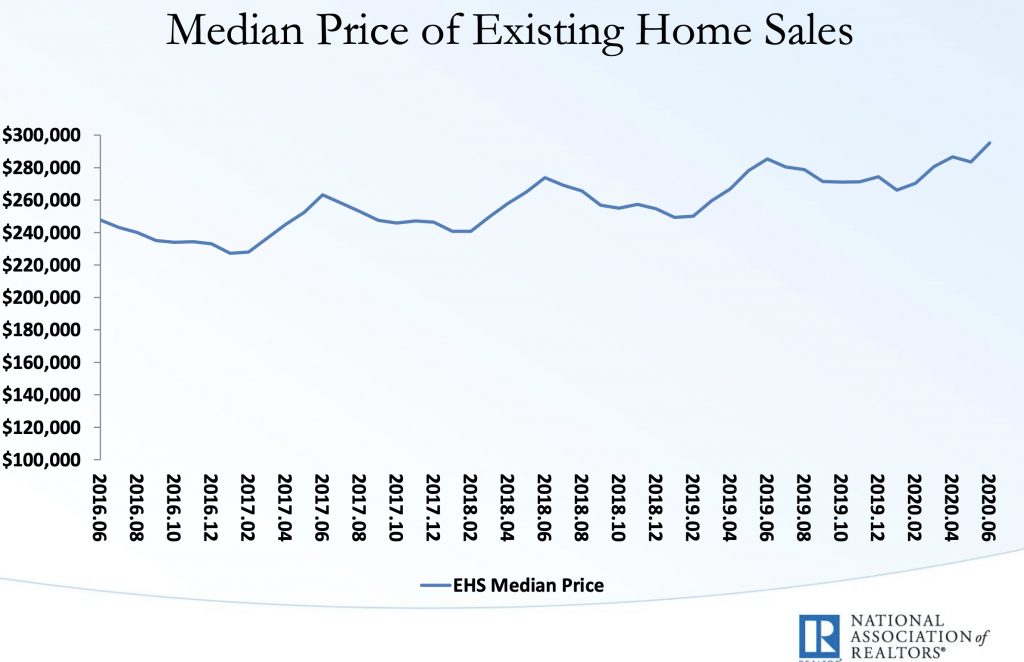

As you can see, the big bound upward in sales really recovered less than half of what was lost during the months of the economic shutdown. For now, however, prices nationally are still trending higher:

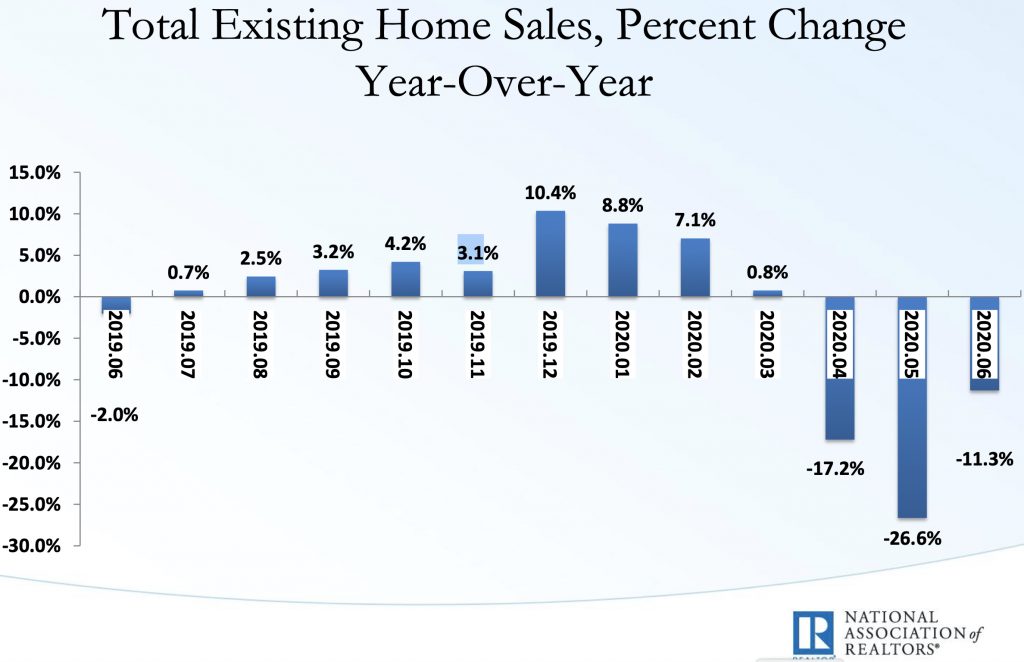

Housing prices fell fractionally in May and April (month on month, but remained up almost 5% year on year), then they rose in June. That is against home sales that look like this year-on year-for each month:

You can see that nationally sales of existing homes were down from the previous year during each of the last three months, though June was not as bad YoY as the months before. So, there has been some recovery, but we're still down more than 11% from the same time last year.

I think that might be as good as it gets, year on year. June and August are usually the seasonal highs, and June happened to time out with a big boost from reopening. August won't have that as we are slowly reclosing or tightening back up on social distancing requirements. (Seasonal changes are irrelevant when comparing year-on-year anyway because you will be comparing to the same kind of seasonal uptick during the previous August.)

There is a caveat, of course. If people move out of big cities, resulting in rising inventory and falling prices in the undesirable cities, sales and prices will rise in small towns and the desirable countryside. And the amount of actual movement, versus just rising inventory up for sale, could be somewhat curtailed over time by the inability of people in the city to get the prices they hoped for.

The major migration reversal

It is important to understand how much and how rapidly the Coronacrisis is reshaping the demographics of the housing market; but it will be another matter to discern whether this is a panic-based fad or an enduring trend.

With tens of millions of Americans out of work, people fleeing cities for rural communities, others working from home, online shopping flourishing, and the virus remerging in many states forcing governors to pause or reverse reopenings, consultancy firm KPMG International has some bad news for those betting the economy is going to "rocket ship" recovery as President Trump boasts about at press conferences and on Twitter. The consultancy firm warns "social-distancing measures" will "dramatically cut the amount of miles Americans travel by car" (fewer miles driven is terrible news for an economy driven by consumer spending).

"The effects of COVID-19 will be felt for years. The response to the virus has accelerated powerful behavioral changes that will continue to shape how Americans use automobiles. We believe the changes in commuting and e-commerce are here to stay and that the combined effect of reduced commuting and shopping journeys could be as much as 270 billion fewer vehicle miles traveled (VMT) each year in the US." -KPMG

If KPMG is right, the change in commuting is massive. When people have that much less commuting to do, they don't worry as much about the distance they have to commute. Some will work remotely almost all the time. Others will commute once or twice a week for meetings. That broadly opens the rural environment to new suburbanization.

While I personally feel intensified suburbanization of the countryside is horrible, that's neither here nor there. We often destroy the features of the areas we like by all moving there or traveling there, and it looks like we're about to do it again.

Because so much of American society is built around the automobile, the changes noted by KPMG are going to impact all kinds of things like parking lots, streets, available gasoline taxes and licensing taxes for maintaining streets that are larger than they now need to be.

(As a side note to the intent of this article, think of what this is going to do to the auto industry -- KPMG's main theme -- crashing the prices of both new and used cars as there is lower demand for the former and sudden high supply of the latter by couples who don't need two cars because they're no longer commuting in different directions or at different times. If you followed my thoughts on Carmageddon during the past two years, you know it just got so much worse!)

We don't know, of course, if this shift to working remotely is permanent, but we do know that a lot of people like the shift to remote working and that a lot of businesses appear to be liking it. Even if businesses don't like it, they may face a hard time getting employees if they don't provide that option because employees do like it and are concerned about congregating. On the other hand, when unemployment benefits dry up, people will take whatever job they have to. It's hard to say how these complexities will eventually work themselves out.

For the moment, here is where we are: Businesses had been reluctant to make the shift to remote working that technology made possible because they didn't trust employees to work at home or think projects could be done efficiently with people not meeting together. Forced to make the change, many employers found employees became more productive at home, so their reluctance started giving way quickly to the hope of saving money on office space and to the need to address employee reluctance to go to work and get a disease.

However, that is far from being an assured trend:

Four months ago, employees at many U.S. companies went home and did something incredible: They got their work done, seemingly without missing a beat. Executives were amazed at how well their workers performed remotely, even while juggling child care and the distractions of home. Twitter Inc. and Facebook Inc., among others, quickly said they would embrace remote work long term. Some companies even vowed to give up their physical office spaces entirely.

Now, as the work-from-home experiment stretches on, some cracks are starting to emerge. Projects take longer. Training is tougher. Hiring and integrating new employees, more complicated. Some employers say their workers appear less connected and bosses fear that younger professionals aren’t developing at the same rate as they would in offices, sitting next to colleagues and absorbing how they do their jobs.

Months into a pandemic that rapidly reshaped how companies operate, an increasing number of executives now say that remote work, while necessary for safety much of this year, is not their preferred long-term solution once the coronavirus crisis passes....

“There’s sort of an emerging sense behind the scenes of executives saying, ‘This is not going to be sustainable,’†said Laszlo Bock, chief executive of human-resources startup Humu and the former HR chief at Google....

The trendiness of the move to working remotely may depend on how long we continue to feel threatened by the virus and, therefore, are forced (if not by our own concerns, then by the concerns of others) into changing our way of life. The longer we work remotely, whether by choice or government mandate, the more accustomed to it we will become.

There are also only so many homes available in the country, so we will have to build new suburbs further out, and doesn't that largely negate the health benefits that are desired? (But that limited supply of rural homes does put upward pressure for sure on the country homes that are available.)

While it is far too early to know if remote working is going to be a lasting trend, property prices may face upward pressure in the countryside at the same time they are facing downward pressure in big cities because we have in the course of three months started to reverse a migratory trend that has existed for decades -- if the new trend holds.

So, if you want to save money on housing months from now, you may have to look for something closer to town ... or in town. You'll have to weigh the savings against your perception of viral risk and risks from social discord. In time, those who can adapt and move against the flow may save themselves a lot of money.

They may also be moving into areas of future blight if they are not careful. It depends on how severe the outward migration becomes. Does it seriously impact tax revenues, leaving cities destitute and unable to conduct routine maintenance as the population no longer supports the infrastructure and buildings remain vacant?

Is the city defunding police at a level that threatens your security? Will that accelerate urban decline? Will it become a neighborhood where you are surrounded by vacated houses? How serious and long-term will the migration be? If concerns about COVID-19 are resolved, will the area return to normal in a few years, or is the outward-bound migration going to remain permanent because remote working becomes the new norm?

There is no trend in place here yet to go by. It's far from a certainty, but urban flight is something to be keenly aware of if you are thinking about buying a new home in the next two years. From the present vantage point, we can only see the new expediency working on people and the ways they are initially responding.

Many workers are loving the remote work, but employers are starting to doubt it again as the novelty wears off. Workers now appear to be turning more slack who, at first, became more productive when they were scared of losing their jobs but now are more comfortable with their situation.

Yet, social distancing will continue to force many employers and employees to remain in this mode for another year. During that time, employers may find ways to deal with the problems. Most likely, it will work out for some companies that will stay with it beyond the coronacrisis and not for others who will return to having most employees work at the office. Others will adopt a hybrid situation. Many jobs, of course, like manufacturing, have to be done with everyone working together "at the plant."

Also, not all workers liked the change, and many who do right now might find its not so great when the novelty wears off. A few months does not a new trend make.

For employees, the move has to do with more than there being no need for commuting or with viral concerns. They also are not finding urban pleasures that pleasurable under partial reopening with so many venues and big events like concerts closed down. So, the urban life suddenly lost the appeal it had for many. If the disease is tamed, however, that will change again. So, there is no assurance this is a longterm shift.

Thus, migration to the countryside has begun, and that may hold the prices of rural real-estate up if this continues as a trend and the countryside gets turned into the new suburbs, which could bring down the price of urban real estate. Areas hit the worst by COVID-19 are likely to fall the fastest and the most in value.

The viral impact on new-home construction

In a healthy market, one would think new home construction would be on the upswing. Do we have a healthy market? Here's what new-home construction, alluded to at the start of this article, looks like on an historic scale:

You can see, housing starts (single and multi-family) have remained weak ever since the housing market collapse that gave us the Great Recession. We barely recovered to half the level we had seen before the Great Recession.

After a brief recent surge at the start of this year, housing starts are now down to the red dotted line, a level that is almost exclusively the range seen in recessions.

The secular trend for the home-construction market looks even weaker when you adjust it for population growth:

This weakening construction growth over many decades, relative to population growth, puts us weaker in new-home construction in terms of need than at any point in history, other than the Great Recession and the recovery period after that.

A weak flow of new homes being built translates into low inventory up ahead. It is this low inventory that is holding housing prices up at still-rising and already astronomical levels in many places. The first full month of reopening released a surge of inventory but a seemingly smaller surge of demand, so that pressure on prices could diminish wherever inventory grows faster than demand.

People have to sell their urban homes before they can buy rural ones, and they're going to have a tough time of that if they don't start dropping prices quickly, but that reality will also make the move look less desirable, causing people to take their homes back off the market if they can't find buyers at the price they are hoping for.

That's a look at where we've been that explains why prices remain higher across most of the nation than they were at the peak we hit in 2007 and higher even than there were just before COVID-19 hit. Will there be any give in prices in order to push those urban sales so people can make the rural purchases they want to?

Hope on the horizon for first-time buyers

If you're a buyer who feels permanently locked out of the market, COVID-19 is bringing you hope -- not promise yet but hope if you hold out.

If you are a first-time home buyer, you have no rising equity in an existing home, and prices have been rising faster than you could save up a downpayment. So, by way of encouragement, let me start off by telling you my experience in that same situation and how it was resolved by the Great Recession, which could now happen for wannabe homebuyers again.

Just before the last housing crisis, I believed I was permanently locked out of the market. I had worked in jobs that required me to live onsite at the resort properties I managed, so I had not purchased a home for years.

That meant I had no equity gain over all those years that I could roll over to buy a house when I finally moved to a position that allowed me to live off the resort. All I could do was rent. I couldn't even hope to save a downpayment faster than prices were rising because I lived in Hawaii where real-estate was sizzling-hot.

Then the great collapse came. After a couple of years, I was able with my wife to buy a forty-acre farm with several large outbuildings in the foothills of the Cascades, surrounded by 360-degree mountain views, running streams, and lots of wildlife. We got it for a dream price, given former prices in our area -- $420,000. We just sold it for $685,000.

I share that to say, an economic collapse can be an equalizer for people who have watched the rich grow richer. It's a reset button. So, don't give up hope, but this time is much trickier. In 2007, real estate was the cause. Now it is just one of numerous areas of impact.

Here is what you need to realize. Housing prices are the last thing to drop in a deflationary situation. Houses are most people's greatest asset and prized possession, so homeowners resist dropping price until they are forced to do so. Things have to be bad for awhile with no outlook of getting better anytime soon before homeowners stop dropping what they will take on their most-prized asset.

You essentially have to start seeing people who are forced to sell. It typically takes, at least, six months of crashing employment to increase the foreclosure pressure long enough to get prices to start coming down, and we've only had four with some reprieve by the reopening, and we have forbearance, stimulus checks, and expanded unemployment benefits keeping foreclosures at bay.

One reason we just sold our farm is that I believe the attainable price had attained its peak. I wouldn't sell just for that reason, as a farm is great to own in a time when there could potentially be food shortages, and I love living here.

Now that we are sliding back into partial shutdowns and even full shutdowns in some states, we may again see food processing plants close and warehousing facilities shut down and see farms at time of harvest that cannot get harvesting crews because their work environments are not considered safe; so owning a farm may be even more valuable if you need food, but small acreage on good land will suffice for that.

However, my wife and I already planned to retire in 4-5 more years, and retirement always meant for us we'd have to sell the farm and downscale in order to eliminate our mortgage so we could afford retirement. Buying an appreciating property and then using its equity to become mortgage free was always part of our retirement plan, and my hope was to time the sale with the downturn into the Epocalypse and rent through the price slide in order so we would not have to downscale to much to become mortgage free.

Here's where having an idea of what is coming can help you survive a crisis: Prices have never been higher in our area. Believing that prices will be pressured to start coming down in the months ahead, a year or two from now may be a good time for someone trying to downscale in our area to buy in again without having to downscale too much.

So, we worked out a deal where we can live here until spring at greatly discounted rent so we can see whether housing prices really are starting to slide and determine then whether to wait the slide out awhile longer or jump in and buy.

Some major caveats

I'm fairly sure we don't have to worry about prices going up any later on this year due to the housing market; but we have no idea how far the government and Fed will go to keep forbearance running and to keep people in their homes and keep housing prices from falling.

It is questionable in my mind that they will prove capable of doing that for long -- any more than they were able to prevent the last housing crisis -- but we also don't know what the Fed's massive money printing will do to general inflation. If we sell and bank our dollars, what will they be worth in a year ... or two? So, prices may not rise due to the housing market, but could rise in dollars due to a general decline in the value of the dollar.

This deal gives us time to wait and watch. If we see inflation picking up generally across the economy, we can buy now with cash in hand, and I anticipate we'll buy a one-acre property, instead of 40, where we can still grow our own food if need be.

(As I've said recently, I've never paid attention to the hyperinflation arguments of Peter Schiff and others for the past ten years, as I was certain hyperinflation would not happen during that highly deflationary situation because all the money was staying in stocks and bonds; but now, with money printing amped up even more and the Federal government joining the Fed in MMT, giving helicopter money to the masses (like the additional $1,200 Fed-funded stimulus check that now looks likely and the Paycheck Protection Program), inflation is a realistic possibility.

Those measures, are for now actually making personal income higher during this layoff than it was before the Coronacrisis, making this the "strangest recession in history." But how long can that continue? Already, the Republican side of congress is getting weary of it all.

Still, all of that is happening in an extremely disinflationary environment where real unemployment frozen well over 20% (probably actually around 30%), so I don't know that inflation will be a problem. I'm just saying there is a higher chance now than there was in the past decade, and the Fed is losing control of an increasingly complex situation in a world that, as I wrote about in my last Patron Post, is trying to break free of the dollar ("Death of the Dollar: Economic Collapse Certain").

So, if you decide to wait out falling home prices, which won't likely start to appear until October or November, keep an eye on general inflation, and know that you may have to wait two years before the economy takes housing prices to their bottom as falling dollar value becomes a threat finally worth actually watching.

Still, there are caveats to the caveats right now: Unemployment has stopped going down, and remains at Great Depression levels, which is a highly deflationary force. Though Government has offset unemployment's deflationary effect with mandatory "forbearance" that has prevented banks from repossessing, many people have not qualified for forbearance.

Those who remain unemployed will sadly lose their homes when forbearance and unemployment benefits run out. Those who never got the benefit of forbearance will be thinned out even sooner. Their homes may start to hit the market as early as this summer.

I suspect the government will stretch forbearance because it has to in order to keep the nation out of total economic despair; but, even as forbearance and unemployment benefits continue to stretch on, it will become harder and harder for those homeowners to eventually make up those missed payments. Many may want to get out before the payments they need to make up destroy all their equity.

Finally, when forbearance does run out, you are likely to see a lot of foreclosures adding inventory to the market, but who knows when that will happen or what other programs the government will invent to stall that disaster? So far, distressed sales are about on par with last year because of forbearance, stimulus checks, etc. and intensified unemployment benefits -- all mitigating factors.

The pressure is building and will continue to build for a long time

This is a longterm downturn, so many plans will be invented to avoid economic disasters of innumerable kinds in the years ahead, but many people will fall beyond the safety nets, too. As the problems grow it will be harder to fence them all off and keep everyone safe from the economic collapse that is happening all around us.

As I posted from a couple of articles earlier this month....

Despite relatively steady home price appreciation in May, the U.S. housing market is on the precipice of an extended price slump, according to a CoreLogic report released Tuesday. The housing data provider’s May Home Price Index and HPI Forecast report predicts a year-over-year home price decrease of 6.6% by May 2021.

Nearly Half Of Americans Consider Selling Home As COVID Crushes Finances.

As the virus pandemic has metastasized into an economic downturn … new research offers a glimpse into struggling households…. Out of the 2,000 American homeowners polled, over half (52%) of respondents say they’re routinely worried about making future mortgage payments and nearly half (47%) considered selling their home because of the inability to service mortgage payments.

That all adds up to my thinking there is a good chance real estate will start to fall in all areas -- not just urban areas -- once the initial panic wave of rural migration slows (if it does) and particularly once foreclosures and bankruptcies start playing through, as they are likely to do later this summer and increasingly in the months ahead.

This is a stay-nimble, stay-vigilant environment with no easy answers. We're all flying the by the seat of our pants because none of us has ever seen a plague-related recession and we have no idea how long the government will maintain all of its support programs or what new ones it might create. (For example, though forbearance ended this weekend, it could be rapidly put back in place; but will it go back before the eviction notices all get sent out?)

Interest rates are at record lows, and those lows are attracting buyers, which also accounts for prices remaining up because lower interest offsets rising prices, and home purchasers buy payments, not prices. However, those rates will stay low for a long time because there is no chance the Fed dares to raise them for years. So, I wouldn't worry about losing that opportunity, and the flood of people initially pulled in by low rates will work through this summer. Rates may go up and down some, but they'll stay in a very low range for a very long time.

Sales usually drop in October and on through the winter months anyway; but, if COVID does pick up due to schools reopening, sales will likely drop more due to more social distancing requirements going back into place. Those who have to sell will have to lower their prices to find buyers.

This housing market will not crash as easily as the last market because it was not built with the same excesses that caused the last one to crash into its own vacuum. There is not the high level of overbuilding that existed before the last crash. There is not the same high level of dependency on adjustable-rate mortgages, which became time bombs when prices started to fall so homes lost equity and couldn't be refinanced or resold when the higher rate adjustment kicked in. Credit terms have not been as sloppy:

The median FICO score at the end of the last expansion was 770, showing a responsible lending market and therefore a housing market that is better prepared to weather the storm.

Even the bottom tiers of the lending spectrum have become more conservative, with the 25th percentile credit score at 716 and 10th percentile at 661 at the end of 2019. Experian typically considers those that have a credit score above 670 as prime.

This compares to the end of the housing bubble when the median, 25th and 10th percentile credit scores bottomed at 707, 639, and 576, respectively.

This is, in a sense, an ordinary housing market decline caused by recession, but this is far from an ordinary recession, leaving us all far from certain how far the housing collapse will go. It's not just a COVID crash; it's an economic collapse due to the failure of the Everything Bubble over chasms of debt at a time of diminishing returns for the Fed that are pushing the Fed to greater extremes with poorer results (as we see in a stock market where the vast majority of stocks have not made it back to the level from which they fell even with trillions of new Fed dollars trying to push the market up, continuing at 1.5 x QE3 every month).

Watch the above forces to see which are holding as trends and which are diminishing.

Election year complications

An election year can hugely change the political solutions that will be tried in the next year under different political chemistry, but also this year as a president does all he can to avoid having the economy fail on his watch because presidents do not get re-elected (historically speaking) in this country when economies fail.

If Trump and the Republicans win, the economy will remain reopened; but economic stimulus will tighten as will unemployment benefits and similar programs that are keeping housing prices up in the face of high unemployment. And Trump, with no concern about ever getting re-elected, will do whatever the heck he wants in a world that is already enraged against him; therefore, the kind of social unrest we've been witnessing will explode.

If Biden and the Democrats win, the economy will be closed back down due to COVID-19, and we may go full socialist retard, printing money without restraint to save everyone any trace of pain by guaranteeing everyone basic income. Then we will all have tons of money to spend, though unemployed, but nothing to spend it on because no one is at work producing anything. In that case, we'll end up with something like hyper-stag-flation.

Expect a circus either way because neither party appears to be led by rational thought, wisdom or vision. Expect bankers to get richer. They always do. They own the White House now, and they'll own it if Democrats win, too.

While I'm not able to state with certainty the housing market is going to crash, I think the overall tilt is in that direction, and this is a good list of the forces to be mindful of. As Louis Pasteur is credited with having said: "Chance favors the prepared mind."