Fed Fights Catastrophic Financial Collapse

Let us begin with an overview of the past season's dramatic financial interventions in pictures.

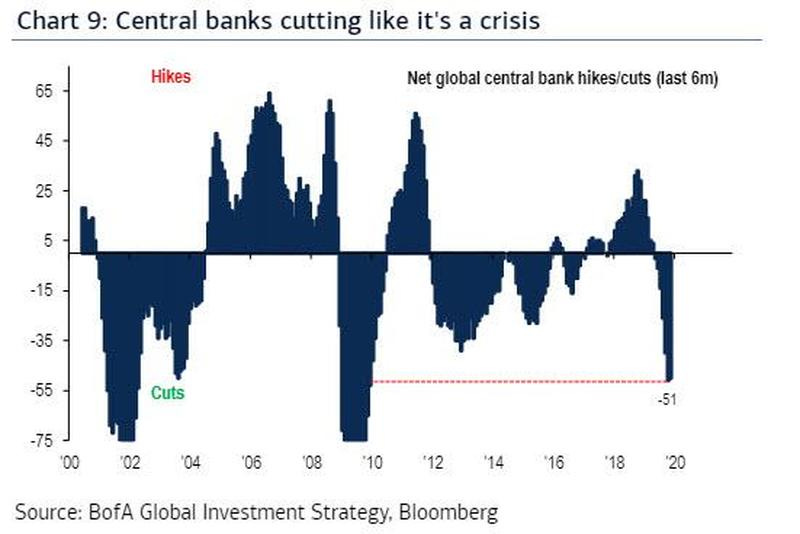

First, here is a picture of global central bank interest-rate cuts and interest-rate hikes over the past decade. As you can see, the masterminds of master finance are currently cutting interest like there is no tomorrow ... as though, without their intervention, there would be no tomorrow ... or as though we were in the throes of a great recession:

While a close-up of just the Fed looks like this:

Just the repo part of that (i.e., not counting the Fed's outright treasury purchases) looked like this on a wider historic timeline:

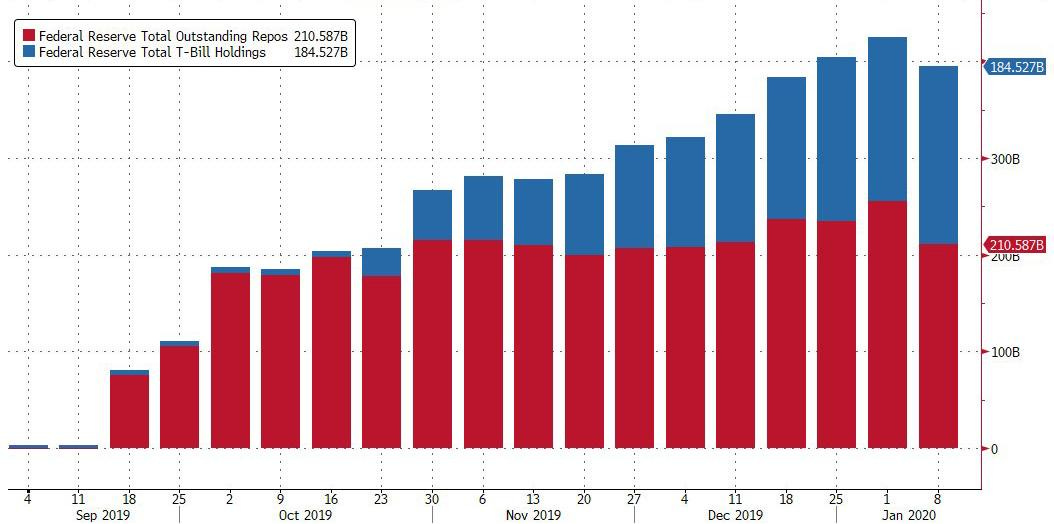

By the end of the year, the Fed's accumulated aggregate in liquidity actions was pushing toward half a trillion, which looked like this:

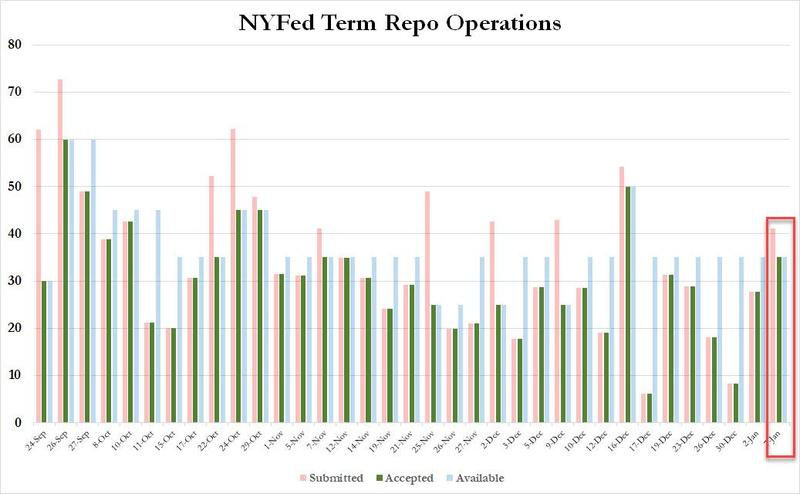

The demand for Fed repos, as we cruised through the close of the year, however, backed off, so the Fed may not reach the half trillion it said it was prepared to offer as soon as the Fed projected:

Oops, not so fast. Just when it looked like pressure on repo was going to turn down because the change of year went by without a hitch ...

... it was back like the endless return of the Alien. (Remember "She's baaaaack?") Available Fed repos became slightly overscribed again, due in part to the timing of term repo roll-offs from December, making it not so clear where things are going from here.

(As a refresher, if needed: Repos are repurchase agreements in which a bank sells another bank a US treasury (or another kind of bond) in order to get overnight cash from that sale with an agreement to "repurchase" the treasury back the next day at a slightly higher price, allowing, thereby, interest on what is effectively an overnight loan. When the Federal Reserve steps in as the buyer of those treasuries, it creates money out of thin air in the member bank's reserve account in exchange for temporary ownership of the treasury. Later, it returns the treasury and zaps the money plus interest out of existence from the member bank's reserve account. If it keeps rolling that over with new repos, however, the money stays in existence for as long as the Fed keeps things rolling.)

For the time, $410 billion in accumulated new money was just enough, at least, to avoid the Repo-Crisis return that was feared for the year changeover from 2019 to 2020. The Fed's response to the crisis was similar to that made in the year changeover from 1999 to 2000 just ahead of the dot-com bust a few months later. So, where are we now?

Stocks are Fed up

The big concern now has moved on to the days around tax day on April 15th when the government will be clearing a lot of tax transactions. Meanwhile, all of the Fed's new money is pushing stocks back up, which is why Zero Hedge noted that "Morgan Stanley Sees Melt-Up Lasting Until April, After Which Markets Will "Confront World With No Fed Support."

Pushing stocks up, you might think, is the Fed's intent with all this repo intervention (and maybe in part it is), but there is something far worse and more insidious driving it, which I'll get to. Still, let's take a look at the stock effect, as it is of no small import, given how precarious I just showed in my last article the whole market has become.

There are really two questions to consider for ascertaining when the stock market's melt-up will end. One is what the Fed will do in the months ahead. The other is what businesses will do in terms of stock buybacks -- the latter still being tied to Fed actions in that buybacks were entirely fueled by Fed free money (and low-interest money) until the government allowed massive repatriation of foreign profits at new lower corporate tax rates. That makes the Fed the biggest factor now that repatriation money is waning.

The correlation between the Fed's repo intervention and stocks couldn't be more obvious:

Here's another perspective of how the stock market has correlated with Fed repo actions of late now that the Fed has returned to quantitative wheezing:

Even the Fed now openly acknowledges this tight correlation:

“It’s a derivative of QE when we buy bills and we inject more liquidity; it affects risk assets. This is why I say growth in the balance sheet is not free. There is a cost to it.â€

That correlation is critical this month because the Fed indicated back in December that it would keep expanding its balance sheet via repos until mid-January after we cleared the year-end hurdle. It's a little less clear whether it planned to start diminishing its balance sheet when repo declined in that it is continuing its US treasury asset purchases until April.

The Fed does, as shown via the Fed's own writing in previous Patron Posts, need to maintain its argument that all of its QE, since the very beginning, is temporary. It has to do that in order to maintain the position that its actions are not permanently financing the US debt, contrary to law. (Laws, of course, can be rewritten when needed, and probably will be soon.)

To the extent the Fed does try to reduce its balance sheet, the correlation shown in the two graphs above (and just logic) says the stock market will start declining ... just as it did as soon as the Fed put its quantitative tightening on autopilot in the final quarter of 2018.

As noted in my last regular post, the market is now more precariously overvalued by numerous metrics than at any other time in history. That means the market is likely to be hypersensitive to any changes in Fed policy. A small miscalculation may be all it takes for the market to fall apart like it did during the dot-com bust when the Fed backed away from its Y2K financial loosening.

So long as the Fed continues expanding it balance sheet, the market melt-up will become further and further stretched above all economic reality by all valuation measures. Even if the Fed just stops expanding its balance sheet but doesn't diminish it, I think we know what happens. Investors don't keep putting money in stocks when stocks stop rising; so, the money will start to move elsewhere, and stocks will start falling. Once they do start falling, that can catalyze an overall reaction out of stocks.

If the Fed starts taking even a little money off its balance sheet, it won't get far with that attempt in a market that is hyper-dependent on the Fed and, therefore, over-sensitized to Fed moves. The Fed will have to return immediately to easing, making the argument that it is temporary even harder to maintain -- though it does still have the willing denial of most of the populace, nearly all politicians, and nearly all financial writers.

When markets are underFed, they throw a fit

Make no mistake about it, the federal government is compounding the Fed's problems with all of its sizably growing treasury issues. When the Fed tried to get out of being the government's lender of first resort, it resulted in the Fed's member banks that are primary bond dealers getting force-Fed more US treasuries than they could resell.

Their individual balance sheets went from high cash reserves to lowering reserves and high treasury holdings. This is what set up the Repo Crisis because banks that are loaded up on orphaned treasuries are not so inclined to take more treasuries as collateral for repos because 1) they already have more than they want on their books; 2) their cash on hand in the form of excess reserves is barely enough to service their own needs or meet their own reserve requirements.

As John Mauldin of Mauldin Economics notes,

The US government ran a $343 billion deficit in the first two months of fiscal 2020 (October and November), and the 12-month budget deficit again surpassed $1 trillion. Federal spending rose 7% from a year earlier while tax receipts grew only 3%.

Let me pause to note here that the part of tax receipts that did the primary growing was tariffs, so as tariffs are rolled down a little under the Phase One deal, this problem of the government's growing need for financing will grow worse, pressing either the Fed or its member banks to absorb more treasuries, making member banks even less willing to do future repos.

No problem, some say, we owe it to ourselves, and anyway people will always buy Uncle Sam’s debt. That is unfortunately not true. The foreign buyers on whom we have long depended are turning away, as Peter Boockvar noted this week.

"Foreign selling of US notes and bonds continued in October by a net $16.7b. This brings the year-to-date selling to $99b with much driven by liquidations from the Chinese and Japanese.... Thus, it is domestically where we are now financing our ever-increasing budget deficits."

That problem may right itself some. Chinese buying of treasuries went down, in part, because Chinese trade went down. Foreign exchanges rely on treasuries as a way of moving money in different currencies. So, with China moving back to more trade, it might move back to purchasing more US treasuries. It's hard to say because China would love to see the US dollar lose its hegemony, so they won't likely buy any more than they can avoid; but expanded trade does create a need.

It will be real interesting to see what happens in 2020 to the repo market when the Fed tries to end its injections and how markets respond when its balance sheet stops increasing in size. It's so easy to get involved and so difficult to leave.

Indeed. The Fed has alway had a much harder time finding exits that work than with creating on-ramps.

The Fed began cutting rates in July. Funding pressures emerged weeks later. Coincidence? I suspect not. Many factors are at work here, but it sure looks like, through QE4 and other activities, the Fed is taking the first steps toward monetizing our debt. If so, many more steps are ahead because the debt is only going to get worse.

Those that believe that the Fed will begin undoing what it has done since September after the year-end “turn†are either going to be proven right or they are going to be proven wrong in Q1 2020. We strongly believe they will be proven wrong. If/when they are, the ... view that the Fed is “committed†to financing US deficits with its balance sheet may go from a fringe view to the mainstream.

If it does go mainstream, that's where the arguments begin because ...

Both parties in Congress are committed to more spending. No matter who is in the White House, they will encourage the Federal Reserve to engage in more quantitative easing so the deficit spending can continue and even grow.

And that's illegal. The Fed may have to drop all pretense that is is not monetizing the US debt when it moves to longer-term treasury purchases to keep from skewing the yield curve, as it does when it purchases US debt only at one end of the curve. That may mean laws will need to be rewritten to allow the Fed to monetize the debt. If that happens, though, the transition to an entirely different financial regime is essentially complete, and it may not be possible to get past public worries and arguments about this massive change.

From the initiation of overt monetization of the government debt, it is a slippery slope to Zimbabwe. The rationale will be that governance under Modern Monetary Theory will make that slope different than seen in Zimbabwe or Venezuela -- the difference being that MMT says direct central-bank financing of government spending, while recommended by MMT, must be limited by inflation.

That could prove harder to control than modern economists sitting in their warm classrooms can even guess because markets will keep demanding more so they can keep rising, regardless of what is happening with inflation. Stopping the flow will mean crashing the markets, which won't sit idly by as they do in theory classes if money creation through government debt purchases stops.

The Fed's global nest of markets will all start shrieking if Father Fed stops bringing home the worms. It's one thing to say, "We'll let inflation govern the extent to which the Fed directly buys government debt." It's quite another to watch all your financially inflated markets starve when you take away the worms because inflation is rising. (And that conundrum is why Zimbabwe became a household word for failed money.)

Mauldin names that regime change like this:

Sometime in the middle to late 2020s we will see a Great Reset that profoundly changes everything you know about money and investing.

That's why you want to be in the know about the fat Fed changes that are now forming and the underlying disease that is really driving these changes even more than markets. The need to move to more direct Fed funding of government and other entities because member banks cannot choke down more US treasuries likely means the MMT enthusiasts are in the ascendancy. Their formerly fringe arguments are now often seen in mainstream publications.

That's why I'm going to lay out the seriousness of the underlying problem beneath the Repo Crisis or Repocalypse.

Monetizing the US debt forever

Even now the Fed's direct monetizing of US debt (turning it into money by buying the government's bills, notes and bonds from the Fed's member banks in exchange for newly created money in their reserve accounts with the intent to hold that debt and roll it over forever) is so thinly disguised one cannot really call it an arm's-length arrangement. It is, at best, a finger-length arrangement.

Zero Hedge recently clarified how precisely the Federal Reserve already covertly monetizes debt the treasury has just issued -- as in buying the exact same debt, not just the same amount, before the banks even have to pay for those treasuries: (Talk about a rapid pass-through.)

The New York Fed was now actively purchasing T-Bills that had been issued just days earlier by the US Treasury. As a reminder, the Fed is prohibited from directly purchasing Treasurys at auction, as that is considered "monetization" and directly funding the US deficit, not to mention is tantamount to "Helicopter Money" and is frowned upon by Congress and established economists. However, insert a brief, 3-days interval between issuance and purchase… and suddenly nobody minds. As we summarized:

"For those saying the US may soon unleash helicopter money, and/or MMT, we have some 'news': helicopter money is already here, and the Fed is now actively monetizing debt the Treasury sold just days earlier using Dealers as a conduit... a "conduit" which is generously rewarded by the Fed's market desk with its marked up purchase price...."

The NY Fed's market desk purchased the maximum allowed in Bills ... just a few days later turning around and flipping the Bill back to the Fed in exchange for an unknown markup.

On the face of it, this is not news. I've said for years this was happening all along: the treasury issues some bills, notes or bonds, and the dealer banks buy them at an open auction with the Fed sopping up a great percentage of each issue by buying these treasuries overnight from the dealer banks (to maintain a stable low interest rate for the US government and for the economy which needs low-interest stimulus, many other interest rates being based off treasuries).

What Zero Hedge zeroed in on of note, however, was that the dealer banks never even actually had to settle their treasury purchases with their own money before selling to the Fed. The Fed purchased those same bonds from the dealers between the time the dealer bank agreed to the purchase at auction and the settlement date for the auction, giving all the money needed for the purchase to the dealer bank by creating it in the dealer bank's reserve account plus a profit BEFORE the dealer bank had to settle with the US treasury.

In that sense, the dealer banks really are nothing more than a conduit because, it appears, they don't even use their own money for one second on any of the bonds the Fed soaks up. I think all of us, until now, thought they were using their own money with a backstop promise from the Fed that was an ironclad guarantee they could sell the bonds to the Fed at a profit a day or so after they paid for them; but it is more like the profit is given to them before the bank even has to settle with the government.

As ZH summarized it,

The Fed is now monetizing debt that was issued just days or weeks earlier, and it was allowed to do this just because the debt was held -- however briefly -- by Dealers, who are effectively inert entities mandated to bid for debt for which there is no buyside demand it is not considered direct monetization of Treasurys. Of course, in reality monetization is precisely what it is, although since the definition of the Fed directly funding the US deficit is negated by one small temporal footnote, it's enough for Powell to swear before Congress that he is not monetizing the debt. Oh, and incidentally the fact that Dealers immediately flip their purchases back to the Fed is also another reason why NOT QE is precisely QE4

Let me just make that "QE4ever" because there is no end-game by which the Fed can stop doing this without crashing the whole economy now that it has gone so many years down this road. They already tried stopping, and their fake markets quickly disintegrated into a disaster, forcing the Fed to rewind its unwind (original tightening) over the course of the last four months of 2019 at the quickest rate the Fed has ever moved! (What you'll find even more interesting toward the end of this article is the squalid mess of rampant greed and risk that lies underneath all of this frantic Fed reaction.)

Elsewhere ZH has explained,

The Fed's charter prohibits it from directly purchasing bonds or bills issued by the US Treasury: that process is also known as monetization and various Fed chairs have repeatedly testified under oath to Congress that the Fed does not do it. Of course, the alternative is what is known as "Helicopter Money", when the central bank directly purchases bonds issued by the Treasury and forms the backbone of the MMT monetary cult.

ZH laid out an example of the Fed's treasury transactions this way:

On December 16, the US Treasury sold $36 billion in T-Bills with a 182-day term, maturing on June 18, 2020, with CUSIP SV2.... On December 19, just three days after the above T-Bill was issued and on the very day the issue settled (Dec 19), Dealers flipped the same Bills they bought from the Treasury back to the Fed for an unknown markup.

"On the very same day!" Wow! Until now, I've referred to these as next-day transactions with the Fed where it was presumed the member banks settled with the government first based on a Fed promise and then flipped the bonds to the Fed the next day. It was, however, never even that "arm's length." If there was any time in those treasury transactions through member banks in which the banks used their own money as window dressing, it was a computerized microsecond as the Fed transferred dealer-bank money from the dealer-bank reserves to the government and instantaneously created a larger deposit out of nothing in the dealer-bank reserves from the Fed as the Fed took ownership of the treasuries! I've said for years this was nothing but an overnight passthrough, but ZH has narrowed down that it is so tightly orchestrated, it is not even overnight! And it may not even be a nano-second, as there is no way of seeing which processes through first on the Fed's computers -- the move of member-bank money to the treasury's reserve account or the move of newly created Fed money into the member bank's reserve account. This is nothing but a head fake.

Yet, they have been getting away with it over and over for years.

The Fed ahead

The Fed's chances of getting away with any miscalculation are getting narrower and narrower as the stock market goes higher and higher and as the problems beneath the Repo Crisis (that I am coming to) spread wider and deeper. So, we need to mine for some hints of where the Fed is going.

Powell is stunningly silent about this. That is not a surprise since half of the times he has opened his mouth he has gotten an opposite response from markets to the one he anticipated. It's also not surprising since no financial reporters ever push him with hard questions that demand better answers because they may lose their place at the table if they don't dine courteously on whatever Father Fed feeds them.

I can, however, go back in my time machine to the year 2012 when Powell was not in charge -- back when his words could broker no immediate wreckage, so he felt freer to speak. Back then, I see he was quite a prophet about where the Fed is today:

As others have pointed out, the dealer community is now assuming close to a $4 trillion balance sheet and purchases through the first quarter of 2014. I admit that is a much stronger reaction than I anticipated, and I am uncomfortable with it for a couple of reasons.

First, the question, why stop at $4 trillion? The market in most cases will cheer us for doing more. It will never be enough for the market. Our models will always tell us that we are helping the economy, and I will probably always feel that those benefits are overestimated. And we will be able to tell ourselves that market function is not impaired and that inflation expectations are under control. What is to stop us?

Indeed, what will ever stop them?

Powell even knew clear back at the start of this Fed-created mess exactly what the side effects would be:

Second, I think we are actually at a point of encouraging risk-taking, and that should give us pause. Investors really do understand now that we will be there to prevent serious losses. It is not that it is easy for them to make money but that they have every incentive to take more risk, and they are doing so....

Meanwhile, we look like we are blowing a fixed-income duration bubble right across the credit spectrum that will result in big losses when rates come up down the road. You can almost say that that is our strategy.

It's hard to pick out a part of that prophecy to emphasize, so I emphasized all of it. Here we are. Strategy complete in all markets not just fixed income! Now fait accompli. But where do we go from here? Interestingly, Powell wondered that back then, too:

My third concern ... is the problems of exiting from a near $4 trillion balance sheet.... We seem to be way too confident that exit can be managed smoothly. Markets can be much more dynamic than we appear to think.

Ya think?

Through the entirety of the Fed's QE program, I have maintained that the Fed never had an exit plan that could work. In 2018, we discovered that was true. So, to rephrase my last question a little differently, where do THEY go from here? (Because wherever THEY go, WE go.) I'll show you below that they do have a bit of new plan in place now and just hinted last week at some big changes.

(And, no, this isn't one of those market things that keeps saying "we will show you" until you get to the end where you have to pay them more to get the real goods. They're coming. In this article. Really. But I need to prepare the way.)

Before we go there, you can see in the following updated graph of all Fed repo and treasury purchases of late, the Fed has just tried rolling some of this backward. So, that is our first hint that the Fed IS going to still TRY to prove it can unwind its balance sheet ... again:

That was a forty-five billion dollar drain off of the Fed's balance sheet from its accumulated repos. However, it was offset in part by a slight addition to the balance sheet from its ongoing treasury purchases. Importantly, the drop, as shown in earlier graphs, was due to less demand for some of the repos ... until ... well, until the day when there wasn't less demand.

You see, just one day later, January 9th, the Fed had to pump repos back up again with another $83 billion in repos because of demand.

For the moment, the Fed seems to be letting demand determine whether its balance sheet rises or falls on a daily basis. January 8 was the second tiny drop in the Fed's new easing. I think the fact that the Fed is clearly just doing whatever the repo market demands explains why the tiny drop produced no revulsive reaction in the stock market. The Fed is simply letting funds flow freely through as demanded by others. Whenever its fund offering has been insufficient, it has upscaled the size of the available offering. It only pretends to be controlling how much new money it creates, but really it is following the repo market's demands. The Fed is, as they say, the market's bitch.

Perhaps the stock market's lack of response that day was due even more to the fact -- when you look at the grand scale of all the Fed's recent interventions -- that it wasn't much of a downtick:

I suspect, so long as the Fed is offering as much liquidity as demanded, there will be no serious quarreling from the markets. It will be when the Fed starts providing less than its greedy nest of baby birds is squawking for that problems emerge, whether in the stock market, the repo market, the bond market, or some other as-yet unexpected place.

Wolf Richter described the Fed's recent shrinkage this way:

This decline is so minuscule that you have to put it under a microscope to see it among $4.15 trillion in assets on the balance sheet, but it's the biggest week-to-week decline since July 2019 when the Fed was still engaged in Quantitative Tightening.

Obviously, there is no telling what the Fed will do if something changes. But as of now, various Fed heads have fanned out across the land to pat each other publicly on the back about how well the repo crisis has been resolved – meaning that the Fed feels like it has this now under control and that it can back off with its efforts.

It is Wolf's last paragraph that is my point of concern -- the fact that, as small as the down blip was, it shows the Fed feels more relaxed now, as though it believes it has everything under control and will let immediate demand determine what is needed. The concern that raises for me is how well will months of immediate demand prepare for tax season, which doesn't all clear just on tax day? Will the Fed foresee the size of what is needed any better than it did last September when it thought it had everything under control? Will the market see what is needed any better than it did last September? They haven't proven to be exactly prescient about these things.

Wolf says,

It wouldn’t surprise me if the Fed continues to gingerly drain liquidity out of the money market as it backs away from repo activities and slows down its T-bill purchases as per its announcement that it would do so when excess reserves reach some “ample†level of magic, even as the Fed continues to roll off its MBS at a rate of $20 billion a month.

It won't surprise me either. In fact, it is exactly what I am expecting. My view of the Fed's view of "gingerly" is that it will mean letting market demand determine how much the market needs in repos; but the market cannot know how much it will need when tax day comes. So, we may see more spikes in repo rates ahead as the market figures it out on the fly. (And then there is that major, insidious problem that we are coming to, which no one understands any more clearly than we understood the problems with derivatives at the onset of the Great Financial Crisis that gave birth to the Great Recession.

Though I'd like a stronger hint from the Fed about where it is going, the best we have for now is that we know it has scheduled a small reduction in February for its term repos:

The NY Fed announced that starting February, the term repo, which had been kept constant at a level of $35 billion since mid-December, would be reduced by $5 billion to $30 billion for every new term repo.

Zero Hedge

You can see that in the Fed's latest schedule release below:

That sounds like an experimental attempt to see if the Fed can ween the market off its re-expansion of its balance sheet. I think that will work over time as nicely as throwing gravel into a turbine jet engine. One thing we know we don't know is whether the Fed intends to increase the rate of shrinkage even more in March and April. It probably isn't going to tell us that until it discovers how reactive everything is to its February plan.

I anticipate troubles will start to emerge to the degree the Fed experiments with notching back to find what hidden degree of demand for more repo or higher money supply exists in the vast ocean of marketplaces to which the Fed has attached its globe-encompassing tentacles. That is something for which the Fed doesn't appear to have much foresight based on what happened in September.

This tapering in repo does not mean the Fed's balance sheet will start shrinking again, however, because its wrist-length purchases of treasuries (its debt monetizations) are not set to decline. Instead it means its balance-sheet regrowth will relax a little ... like this now that the Fed acts as though it believes it has this under control:

The "indefinitely" is what makes it QE4ever. Just last Wednesday, the Fed unexpectedly issued a FAQwa that lays out plans for broadening its treasury purchases (weakening even more its last thread of an argument that it is not monetizing the federal debt):

In order to slow the rate of purchases for securities in which the SOMA portfolio already has large holdings as a proportion of Treasury securities outstanding, the Desk will allow the share of SOMA holdings of an individual Treasury security to rise above certain levels only in modest increments ... or otherwise change the stated limits as needed.

Hmm. All rather vague. I raise an eyebrow. Let's read on. (SOMA, by the way, is the Fed's System Open Market Account, which is what they call the account that contains all assets purchased by the Fed on the "open market," including US treasuries.)

For bills, the Desk will allow the share of SOMA holdings of an individual Treasury security to rise above 17.5 percent in increments, as shown below.

So far not very helpful, other than to indicate its newly expanded store of treasuries will be expanding, not shrinking. Maybe it will help if I read between the lines:

First, I see elsewhere in the document that the Fed indicates its reasons for doing this is to avoid cornering too much of one kind of treasury in the market as it maintains its commitment to purchase $60 billion in treasuries each month. In other words, as it's holdings of say 1-year bills starts to rise, the Fed might need to move to other bills further along the yield curve to keep from distorting the curve ... or to keep from totally controlling the value of that maturity of bill.

This could mean the Fed is only going to move to bills of the same duration but with a different maturity date due to a different issuance date. However, my little suspicious mind led me to explore further to see if the Fed is prepping an argument for going to longer duration bills whereby it will be able to say later, "We are not moving to longer duration notes or bonds in order to monetize the debt but just, as we already told you, because we don't want our monetary policy to distort or corner the market in any one particular kind of treasury?"

So, reading along a little further, I did find this statement slipped in:

Consistent with the FOMC directive, the Desk will purchase Treasury bills in its reserve management purchases and purchase nominal coupons...

Oh, "coupons." That certainly indicates something longer-term than the 1-year bills it is currently purchasing. Since that's where my suspicious little mind immediately went, keep an eye on this one. I think they are hinting their next move to go broader spectrum higher up the yield curve. As you'll see in the argument further down, this presents some real issues now that QE is 4ever. Maybe I'm just cynical after so many years of watching the Fed and our national politicians on all this stuff.

Oh, but here we are, as I read even further (and I'm not feigning drama here; I'm actually telling you where my mind went as I read):

The table below includes the specific sectors the Desk will use and approximate sector weights.

There we have it! Just as I was suspecting. The Fed will be reinvesting in longer-term bills on a balance sheet that can never wind down. As its current one-year bills mature, it will reinvest in longer-term treasuries.

But, they will tell you, they are not doing this to monetize the debt!

The Desk’s monthly purchase schedule for reserve management and reinvestment purchases will communicate the specific maturity range of each operation in advance. The Desk anticipates transacting across the full maturity range in each sector for most operations....

Oh, so, it's not just for reinvestment purposes; it's also for "reserve management." And, of course, they will communicate the specific maturity range they are looking for in advance. That's how the pass-through works. How else will the primary-dealer banks know what the Fed will sop up as a nano-second-at-best passthrough? Of course, the Fed will telegraph what it will buy so it's member banks can pass through the right stuff, which will be those treasuries that the US Treasury needs to sell and for which it needs Fed support.

The Desk may not always transact in the sector’s full maturity range for market functioning and operational efficiency reasons. The Desk will refrain from purchasing securities that are trading with heightened scarcity value in the repo market for specific collateral, newly issued nominal coupon securities.

Do you see how the groundwork for the argument is being laid? So long as your intentions are right, what you are doing doesn't matter. So long as you are not doing it with the intention of permanently financing the US debt, but just for the sake of maintaining proper "market functioning and operational efficiency," then it should be fine, right?

That's how slippery these guys are, and you know the federal government will let them get away with it because the politicians we apparently love to vote for need that in order to keep on spending, and you know the financial media will be close to totally silent about it. So, it may just slide right on by ... again.

The critical thing to note here is that they are already openly talking about moving from bill purchases to coupon purchases, relinquishing their argument last fall that none of this was monetizing the debt BECAUSE they were not purchasing coupon-bearing (longer-term) government debt! You could know it was all temporary because it was short-term debt, they claimed. Enter Phase Two where the argument is now forced to adapt.

Additionally, the Desk will not purchase securities with 4 weeks or less to maturity.

Yeah, no sense going too temporary any longer.

Its all due to hedge hogs

Now do you want to know what insidious disaster is forcing this mess, aside from the more benign and obvious overlying problem of a shortage in bank reserves?

The Fed is now the repo market's hostage because it has allowed so many hedge funds to use repos -- something that was not allowed before the Great Recession. Hedge fund use of the repo market has grown unseen by most beneath the surface of the market and was forced into the open when reserves became short and banks became overloaded with treasuries, leaving hedge funds suddenly short on money for their high-risk ventures.

The gist of it is this: hedge funds made great gains off of a high volume of tiny margins by using overnight repos to finance their funny business. So long as everyone was glad to offer repos to hedge funds in exchange for US treasuries, all was well. The extent to which clearing houses could bust if one or two major hedge funds go down because they cannot get their repos any longer is massive beyond even the kinds of collapse we saw in the Great Financial Crisis.

The Fed has engendered a situation that it now cannot back out of without crashing the financial system at its core again along with the whole economy because of the problem's scale. However, the Fed must maintain the illusion that all of its repos are temporary and so are its new treasury purchases in order to keep saying that all of it is "not QE." As I've written before, if you keep rolling the repos over, they are permanent expansion of the balance sheet and, so, are QE in fact because they are temporary in name only.

The mystery of what was happening deep beneath the riled repo waters was laid out by the Bank for International Settlements, which recently issued a report that summarized the repo crisis as a problem with shortages in US bank reserves but pinpointed the main source of troubles:

The mid-September tensions in the US dollar market for repurchase agreements (repos) were highly unusual. Repo rates typically fluctuate in an intraday range of 10 basis points, or at most 20 basis points. On 17 September, the secured overnight funding rate (SOFR) ... jumped ... about 700 basis points.... The reasons for this dislocation have been extensively debated; explanations include a due date for US corporate taxes and a large settlement of US Treasury securities. Yet none of these temporary factors can fully explain the exceptional jump in repo rates....

US repo markets currently rely heavily on four banks as marginal lenders. As the composition of their liquid assets became more skewed towards US Treasuries, their ability to supply funding at short notice in repo markets was diminished. At the same time, increased demand for funding from leveraged financial institutions (eg hedge funds) via Treasury repos appears to have compounded the strains of the temporary factors.

That last paragraph is the whole situation in a nutshell. The BIS further noted that the freezing up of repo markets in 2008 was one of the most significant causes of the Great Financial Crisis. Just as I exposed here over the course of the Fed's tightening regime via one of my own discourses with the Fed, the BIS also now explains ...

After the Federal Reserve started to run down its balance sheet in October 2017, [member bank] reserves contracted, quickly but in an orderly way as intended. Alongside, banks' holdings of US Treasuries increased, almost trebling between end-2013 and the second quarter of 2019 (blue line).

Some people argued with me that this wasn't happening until I showed them an email from one of the Fed's leading economists to me in answer to my own questions. The Fed's member banks, as I pointed out then, picked up the slack when the Fed quit rolling over the US treasuries that had fattened the Fed's balance sheet. If the dealer banks had not done this, US treasury interest would have soared.

As I later pointed out, after the Repo Crisis blew up, the Fed's member banks did this until they became overstuffed with treasuries to where they didn't want to take any more on as collateral for repo loans.

The BIS notes,

Repo rates started to increase above the IOER from mid-2018 owing to the large issuance of Treasuries.

That is also something I noted at the start of 2018 as a serious cue to a problem likely to build into THE calamity of 2018 later in the year. I even pointed out how the Fed seemed to be losing control over its Fed Funds rate at that same time (closely tied to repo actions).

The AIG-sized monster beneath the madness

Later in its report, the BIS gets down to pinpointing the deep cancer in the repo system that is exacerbating these problems we see on the surface. (The rocks beneath the rapids.)

Leveraged players (eg hedge funds) were increasing their demand for Treasury repos to fund arbitrage trades between cash bonds and derivatives. Since 2017, MMFs [Money Market Funds] have been lending to a broader range of repo counterparties, including hedge funds, potentially obtaining higher returns. These transactions are cleared by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC).... The resulting remarkable rise in FICC-cleared repos indirectly connected these players.

Suddenly ...

Market intelligence suggests MMFs were concerned by potential large redemptions given strong prior inflows.

That's why the repo funding available from the Fed's primary treasury-dealing banks to hedge funds via the FICC suddenly dried up! Banks got scared about the risky activity from hedge funds gambling en masse with repos as a source of cheap money for whatever the heck they were doing with .... DERIVATIVES!

Yes, we're back to those nasty derivatives causing serious stress in financial markets, resulting in September's panic seizure of repos, just like in 2008, which the Fed is covertly smoothing over with new massive injections of QE that is "not QE!" (Yet, no one was talking about it. Certainly not the Fed!)

Now, here's the greater and deeper problem: the FICC, a massive clearing house tied up in these repo-derivative bargains, became so financially stressed when repo suddenly seized up that the Fed had to essentially bail them out. As cash reserves became depleted in primary dealer banks (the ones authorized to participate in US Treasury auctions) and they became overstuffed with too many treasuries, they also became increasingly fearful of the hedge-fund game. So, they STOPPED ISSUING THE REPOS VIA THE FICC, putting the FICC on the hook! JP Morgan particularly jarred the system by stepping out of repo. (Some say to intentionally jar the Fed back in.)

If the supersized FICC crashed, that would be as big as the crash of the AIG would have been in the Great Recession, had the Fed not bailed it out.

Yes! We're back to all the same crap, but it is happening covertly. The Fed is not talking about the underlying garbage at all. Had the Fed not leaped in with over $400 trillion, the FICC and other clearing houses would have collapsed.

That close call with an FICC crisis is why the Wall Street Journal reported this month,

Federal Reserve officials are considering lending cash directly to hedge funds through clearinghouses to ease stress in the repo market. But that could be a tough sell for policy makers. https://t.co/CUlI4o943Q

— WSJ Markets (@WSJmarkets) January 14, 2020

The Fed, to avoid another situation where skittish banks cause a repo collapse (and to protect its member banks who own the Fed), wants to resolve the Repo Crisis that will not go away by allowing the desperately troubled clearing houses (like the FICC in particular) to do Fed-funded repos directly, instead of working through banks. That would remove banks from the risk equation, and supposedly keep the banking system from going under if the hedge-fund repo-derivative trade implodes. By removing banks that don't want to take on more treasuries as collateral to hedge-fund risk, they can keep banks from creating waves on top of the repo market. Banks don't want more treasuries as collateral that they could get stuck with if the hedge-fund activity blows up.

The Fed, in other words, is looking at opening up a repo window directly with the FICC and other clearing houses to cut its member banks out of the equation AND to keep the FICC and other clearing houses from blowing up. The FICC is simply too big to fail, and the Fed cannot ween it off of repos because the hedge funds are running their own arbitrage Ponzi scheme, and we all know Ponzi schemes do not shift successfully into reverse and unwind nicely.

As the Financial Times reported

One increasingly popular hedge fund strategy involves buying US Treasuries while selling equivalent derivatives contracts, such as interest rate futures, and pocketing the arb, or difference in price between the two.

It's a trade on narrow marginal difference that is made possible only through the ultimate cheap interest rate made available via repos or Fed funds. You cannot ease out of a Ponzi without bringing it down. If the hedge funds lost their cheap funding via repos, their profit center would seize up. Then money would start siphoning out at even greater speed from already troubled hedge funds. If the hedge funds go down because their cheap funding source that made these marginal trades profitable evaporates, SO DO MONEY MARKET FUNDS (and so does the FICC which gets left on the hook) because that is what happens when you unwind leveraged leverage backwards:

MMFs were concerned by potential large redemptions.... These repos now account for almost 20% of the total provided by MMFs.

So, everything starts going down. The FICC is the greater concern. The Journal noted the parties most at peril from a rewind of highly leveraged hedge funds were the massive clearing houses like the FICC.

The head of one of the world's biggest failing hedge funds, the Horseman Global Fund, explained the risk for clearing houses this way: (You can drill deeper in the following article if you need/want more explanation of these trades.)

Cash hoarding and repo market problems could be a sign of counterparties beginning to worry about clearing houses. If initial margins rise significantly, the only assets that will see a bid will be cash, US treasuries, JGBs, Bunds, Yen and Swiss Franc. Everything else will likely face selling pressure. If a major clearinghouse should fail due to two counterparties failing, then many centrally cleared hedges will also fail. If this happens, you will not receive the cash from your bearish hedge, as the counterparty has gone bust, and the clearinghouse needs to pay from its own capital or even get be recapitalised itself. One way to think about it is that the financial crisis only metastasized when MG failed [mortgage guarantees, such as provided by AIG], because at that point, everyone suddenly became un-hedged, and everyone needed to sell.

As head of a flailing, failing hedge fund, Horseman ought to know if the problem lies with hedge funds. However, I think Horseman is a hedge fund betting against hedge funds. Still, their layout of the problem (given the Fed's response) sounds spot on. Whether Horseman finally triumphs on its own bearish bets will depend on how well the bets are timed (not so well so far) and whether the Fed's emergency response outlasts Horseman (most likely). Horseman explained in another letter to its clients,

Clearinghouses have become the center of the financial system, but they do not bear the cost of any mistakes they make in pricing risks. This is borne by other clearinghouse members. But what the BIS note and the note issued by the banks and other users of clearinghouses makes clear is that the market has become very directional, with banks supplying liquidity to the repo market, while leveraged funds are taking liquidity.... As the near bankruptcy of a clearinghouse highlighted last year, it is other members that bear the risk when things go wrong, and hence big US banks have acted rationally in looking to reduce liquidity to the repo market, which of course forced the Federal Reserve to act.

When banks like JPMorgan stepped out as the source of bottomless Fed repo to clearing houses and, thence, to hedge funds, that left clearing houses at risk because they could not get Fed repo, except through the banks to which all the treasury collateral had passed. So, now the backwash from any unwind would stop at their shores.

There is one insidious little problem with the Fed's plan to do repos directly to or through the FICC (and/or other clearing houses) in order to make sure clearing houses have all the funds the need to avoid catastrophic failure: If the Fed gives an easier, more direct desk for hedge funds to use in arbitraging a trade between Fed repo and derivatives, their use of Fed repo to leverage profits will grow considerably, making the potential for catastrophe far worse down the road. Of course, that seems to be the Fed's modus operandi -- make all things better now by assuring they will be worse later. (Which is why the Fed has a difficult argument to make that happen for the hemorrhaging hedge hogs as a solution that will protect its endangered banks.)

This is leading some within the Federal Reserve to speculate whether or not an entirely new way of doing business within the repo market is needed, one that will cut out the banks as the middleman and allow the FICC (Fixed Income Clearing Corp.) direct access to market participants.

This would add much-needed assurance and stability to the repo markets, leading to less disruptions and freezes as well. However, it would essentially be akin to signalling a green light to those wishing to take on riskier assets, leveraging up and putting the entirety of the system at a greater risk in the long term.

Additionally, this would allow large financial institutions and hedge funds direct access to the Federal Reserve indefinitely, putting taxpayers on the hook for future bailouts.

Well, what could possibly go wrong with that?

The Fed is desperately throwing gasoline all over a world filled with matches, hoping well-fueled liquidity will douse future fires should any match ignite. There's a plan! The Fed should not call itself the "lender of last resort." It should call itself "the fool of first resort." Or maybe "the fuel."

If this market ever crashes you can blame the Fed who was too scared to endure a larger correction when trying to normalize and instead proceeded to blow an even bigger asset bubble with even more liquidity injections.

— Sven Henrich (@NorthmanTrader) January 13, 2020

Let's put out the fire by running a hose directly from the gas tank! Now, how could that go wrong?