The Great Recovery Rewind: An Interesting Interest Conundrum

(This Premium Post, available to patrons who support this site at $5 or more per month, explains how the Great Recovery Rewind works, how it impacts interest rates, and how it may be monetizing the US government debt. It can be opened here with the password provided to Premium Post Patrons or in my posts section of Patreon. com.)

How the Great Recovery worked financially

You probably recall how the Federal Reserve pumped up the reserve accounts of its member banks by buying back government bonds from them in Operation Twist. It said it did this to ensure the durability of banks during the economic crisis that gave us the Great Recession.

Because the Fed is not allowed to purchase government debt directly, lest it be accused of "printing money" to finance the US debt (also called "monetizing the debt"), it telegraphed to its member banks the promise that it would vacuum up all the US treasuries they wanted to buy from the government and sell to the Fed at an overnight profit, making those. banks a mere conduit for soaking up government debt. The Fed, of course, maintained it was only doing this as essential to interest control because they needed much bigger tools to control interest during the financial crisis.

Naturally, the banks bought all the treasuries the government wanted to issue and then immediately sold them to the Fed for a tidy little profit. The Fed paid the banks by creating money out of thin air electronically in the banks' reserve accounts with a few ones and zeroes from the Fed's computers.

The unique privilege national banks have for being part of the Federal Reserve System is that, when the Fed wants to add money to the monetary system, it just creates it in the accounts of member banks. Free money is available only to "national banks," meaning those that are part of the Federal Reserve System.

The Fed maintained that this maintained an arm's-length relationship between it and the federal government -- so that it was not technically monetizing the national debt -- and that it was primarily controlling interest building up bank reserves by doing this so that banks could weather any storm that might come again after the financial crisis. That is how quantitative easing worked.

The Fed justified this statement by saying this financing was temporary so that it was not just soaking up government debt to endlessly roll it over as debt that never needed to be paid back. Therefore, unwinding its balance sheet is necessary to prove it is not going to endlessly carry the government debt it soaked up during the Great Recession.

How the Great Recovery Rewind works

The Fed's balance-sheet unwind plan is to intended, then, to let treasuries mature and not refinance them. I couldn't see how that would reduce the balance sheet. Usually, if a company lets a government treasury on its balance sheet mature, that means the government pays the company the face value of the treasury. The company, then, no longer has a bond on the asset side of its balance sheet, but it has cash in its bank account on the asset side of its balance sheet.

There is no reduction of the balance sheet in that transaction. It is just a conversion of assets with possibly some profit or loss on the conversion. The thing about balance sheets is that they balance because, if you take one thing off the asset side, you generally have to take something off the lability side if you want to keep the sheet balanced but make it smaller.

It's a little different with the Federal Reserve because the Fed is also the U.S. government's banker. Because I wanted to hear directly from the Fed how they can reduce their assets in their balance sheet just by letting them mature and collecting the payoff, I contacted several people at the Fed. Most didn't answer. One of the two who did was Karen Mracek, Coordinator of Media Relations, who basically just responded with "Who wants to know?" Or as she put it,

Can you tell me a little bit more about who you are writing for? Or where and when you expect to publish an article?

Thinking the Fed might not be inclined to talk to people whose writing is usually critical of the Fed, I inquired back,

How would that affect the answer to the question?

... that was the end of correspondence.

I got the feeling the Fed likes to tightly control what it says to whom.

I did, however, get an answer via another person, whom I won't name in case giving answers to unruly, critical writers is against Fed policy. (She was nice, so I don't want to get her in trouble.) To show you how fair I am to the Fed, I'll say I think I got a solid response. This person got me an answer directly from one of the Fed's lead economists about how receiving payouts from the US treasury reduces the Fed's balance sheet, and it actually made straightforward sense:

Basically, when the [US] Treasury pays off a maturing security, it uses revenue from another source, either tax receipts or money obtained by issuing a new security, which reduces reserves in the banking system. When a security in the Fed’s portfolio matures, the Fed, in essence, presents the security to the Treasury for payment. However, the Fed does not receive “cash†from the Treasury – rather, the money is taken out of the Treasury’s account at the Fed (which is a liability of the Fed). So, the transaction results in a decline in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet by the amount of the maturing security (of course, at the same time a lot of other things are going on that affect the size of the Fed balance sheet)....

David Wheelock - St. Louis Fed Deputy Director of Research

So, the Fed loses a US government asset it owned (the security), but it also loses a liability on its balance sheet in terms of the deposits held at the Fed by the U.S. government. (Even regular banks consider deposits liabilities because they might have to pay out cash on those deposits.) Fair enough. Instead of trading one asset for another (cash or money in the bank) as happens with any company that lets a treasury mature and takes the payoff, the Fed trades the asset into the government for an equal reduction in its liabilities to the government.

Mr. Wheelock then kindly explained the second essential step as to how this flows down into actual reduction of money in the monetary system:

...The key to understanding how this affects banks’ reserves is that the Treasury has to have sufficient funds in its account at the Fed to pay off the maturing security. It gets those funds by selling a new security to the public or by taxing the public. Both of those transfer money (reserves) from banks to the Treasuries account at the Fed, thus reducing reserves that banks have with the Fed.â€

In other words, in anticipation of public demand for securities like treasuries, the few banks that are approved to deal in US treasuries (the primary treasury dealers) buy those treasuries in large wholesale purchases from the U.S. government with money they keep in one of the Federal Reserve System's reserve banks. They pay for those bonds by transferring money in their reserve accounts to the US government's reserve account. After buying them from the government, they can hold some of these securities as their own investments or retail all of them. Some of those they sell go to other banks that hold them as assets. (Currently about 20,000 banks in 191 countries hold sovereign bonds as their own assets, and these bonds average about 9% of each bank's assets globally.)

If you come along as a retail buyer and purchase one of the securities that the government issued in order to pay off its earlier security that the Fed was holding, you write a check to the bank that is the government's dealer (or to some intermediary). You get the security, and the dealer bank gets money transferred from your bank to replace what they paid the government for the security when they bought a whole lot of them. (The dealer banks get more from you than what they paid the government, generating a profit to the dealer bank.)

Once the dealer bank gets money from your bank, it can either replenish its reserve account at one of the Federal Reserve Systems reserve banks, or it can invest it some other way, including back into more government bonds. So, you can see how the Fed's roll off of bonds moves through the monetary system. Money banks could have been spent in other ways or that you could have spent in other ways gets tied up in bonds and is kept out of circulation. To the extent that member banks allow this to deplete their excess reserves, they have less in reserves to lend against. So, the banking system tightens up.

An interesting conundrum

The Fed has to know that its balance-sheet unwind will affect interest rates by tightening up available credit, and I have always believed that its unwinding of these treasuries will have greater effect on longer-term rates than its target increases for the Fed funds rate.

The Fed funds rate is the interest rate at which member banks offer overnight loans to each other from the excess reserves they keep on deposit at the Fed. It is in essence the "price" of federal funds. "Excess reserves" refers to any portion of a bank's reserves that is over and above the amount the Fed requires that particular bank to keep on deposit in a reserve bank to cover its loans. Banks loan to each other at a low overnight rate, which enables banks to maintain the reserve balances the Fed mandates for each bank based on how much that bank is carrying in loans, as changes daily. Thus, the Fed funds rate is the most determinative interest rate in the US marketplace — maybe the world, given the dollar is the global trade currency -- because it sits at the foundation level of a bank's ability to make loans.

The Fed does not directly control the Fed funds rate by decree, but it sets a target range (a goal) for the Fed funds rate (the target we hear about more than anything else the Fed does) in order to regulate how much liquidity exists between banks. The more it can keep the rate banks charge each other down, the more readily banks will borrow money from other banks, lubricating the economy. If it want's to tighten the economy, it pulls back on those reins.

The Fed uses its own monetary policies to manipulate the interest rates banks choose to charge each other on overnight loans from their reserves near the center of that range. If the Fed wants to lower interest rates in the general economy, it can do this by issuing credits (free new money created on a computerized bank account with a few clicks of the computer keys) into the reserve accounts of its member banks so that more banks have excess reserves.

The more free money the banks have overflowing their reserve accounts, the more readily they will loan any excess at low interest to other banks whose reserves are shy of their needs. Banks may be shy of their needed reserves because of the amount of loans they just issued, so these interbank loans allow those other banks to issue or carry more loans until they can raise more capital via new deposits or other means to bring their reserves up. This results in more loans into the general economy so more money floating throughout the system.

One of the Fed's favorite ways to issue lots of new money during the recovery period was to buy US treasuries from the banks, which those banks would buy from the government because the Fed is not allowed to buy government debt directly from the government. To entice those banks to do the buying for them, the Fed would promise to buy all the treasuries the banks bought by creating new money in the banks reserve accounts to pay for those treasuries.

Bank reserves are considered the base supply of money in the Federal Reserve System, so helping fund the government in this way inflates the money supply. It also helps the government fund its debt inexpensively because the banks buying the treasuries with their excess reserves were told the Fed would immediately soak them all up and pay the banks enough new money via reserve credits to generate a small overnight profit for the banks on each transaction. So, it helped the government and created a lot of additional financial liquidity in the banking system at the same time.

However, it means the Fed is in essence funding the government's deficits by creating new money at rates far cheaper than what the government would have to pay on the open market IF the Fed was not backstopping all the government's debt issuance with these guaranteed repurchases. The Fed has argued this was not monetizing the debt because the Fed was not going to endlessly rolling these bonds over. It, however, continued to roll them over until it started letting them mature near the end of 2017 and debiting the face value from the government's own reserve bank balance.

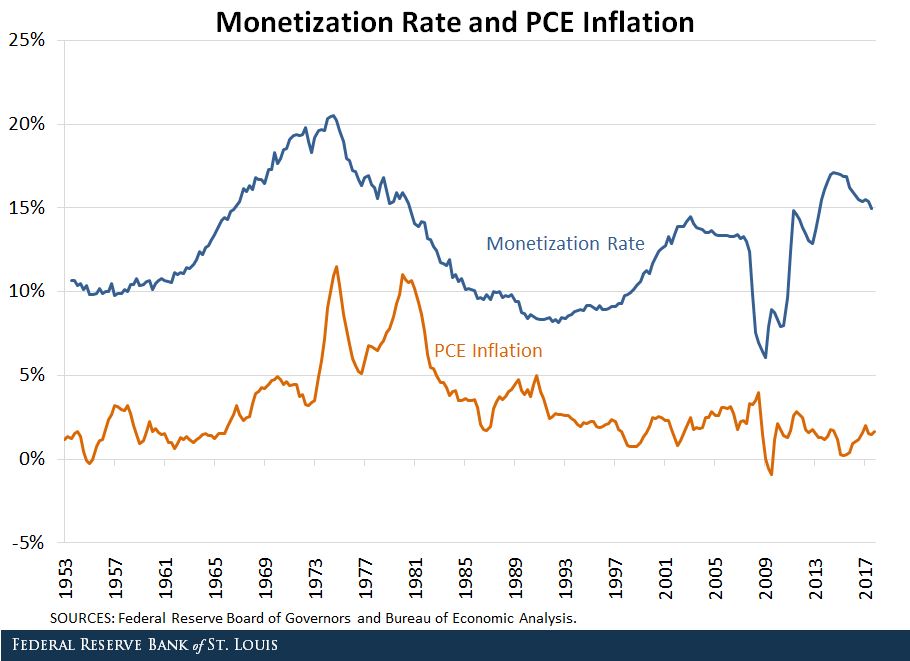

Even the Fed admits to monetizing the debt, saying the percentage of US debt that it has monetized looks like this:

Maybe that's not enough to matter, except that the blue line doesn't show how much debt the Fed's member banks hold on their own balance sheets. It's just the amount the Fed has bought back from its member banks. You can also see that increasing the amount of debt the Fed monetizes caused inflation to increase until lately when the new money primarily inflated stock prices that aren't counted as "PCE inflation" or remained tied up in bank reserves or in banks' government bond holdings. ("PCE" is the designation for "core" personal consumption expenditures, which do not include energy or food because we are supposedly not impacted by those things.) Decreasing monetization (by the Fed's way of accounting for monetization) has dropped inflation in the past.

For those who were not around in the seventies, the inflation caused by the Fed's monetization of debt at 20% of the debt became a huge problem, causing a recession and necessitating a severe credit clamp-down by Fed Chair Paul Volker (wherein mortgage rates rose to around 12% interest and higher). So, approaching the 20% level causes big inflationary troubles if the money flows into the general economy. The key, then, to monetizing the debt without creating inflation is to keep the money all tied up in banks where it does no one else any good.

Until the start of its unwind, the Fed was enabling the government's excessive borrowing by providing qualitatively massive amounts of low-interest loans via its backstop guarantee of repurchases to its member banks. Now that the unwind has begun, the government will supposedly have to pay all those bonds off to bring that line down. That supposedly means the Fed is no longer monetizing the debt, but that is only if the roll off continues, which now appears questionable to almost everyone.

I would further argue that, if the Fed's member banks are now just loading replacement bonds for the government on their own balance sheets at exceptionally low interest, what is the difference? A tad higher interest? Not much if the Fed is still manipulating those interest rates down.

Even the Fed acknowledges this with a caveat:

If the Fed wants to lower interest rates, it creates money and uses it to purchase Treasury debt. If the Fed wants to raise interest rates, it destroys the money collected through sales of Treasury debt. Consequently, there is a sense in which the Fed is “monetizing†and “demonetizing†government debt over the course of the typical business cycle.

However, what is usually meant by “monetizing the debt†... is the use of money creation as a permanent source of financing for government spending. Therefore, whether the Fed is truly monetizing government debt depends on what the Fed intends to do with its portfolio in the long run....

Let me correct that for them. It is not just what it intends to do, but what it actually winds up doing. Without the followthrough, the intentions are void. The intentions mean something only so long as the Fed can be trusted to carry out its stated intentions.

Until the Great Recession in 2008, the Fed only bought enough treasuries off of its member banks to control interest rates; so this monetizing effect of its purchases was not concerning. Since 2008, it has funded trillions of dollars of US debt, making it appear that funding the debt was as much a part of its concerns as using government bonds was a way to manipulate interbank interest rates. Again, the Fed has promised to roll those securities off of its books so the monetizing effect is not "permanent." Otherwise, it turns out it did just monetize the debt even by its own assessment.

The Fed, itself, argued,

If this accumulated Treasury debt is supposed to be permanent, then it is reasonable to expect that the corresponding supply of new money would also be permanent and would remain in the economy as either cash in circulation or bank reserves.... As the interest earned on the securities is remitted to the Treasury, the federal government essentially can borrow and spend this new money for free. Thus, under this scenario, money creation becomes a permanent source of financing for government spending.... Some means other than money creation will be needed to finance the Treasury debt returned to the public through open market sales.

This is why the Fed now believes it has to make good on its promise that the Fed's government funding was temporary (so long as the promise matters to anyone) -- to prove the expansion of its balance sheet was never really about monetizing vast amounts of government debt by holding it forever at low or no interest. The Fed's great unwinding is supposed to send the government packing to other creditors to fund this debt.

Because the Fed's unwind appears to be causing major problems in the stock market, the Fed reversed itself and announced that it will slow down or pause its unwinding if necessary. I've always said its unwind is certain to cause problems. That is why the Fed is now having to say this almost as soon as its unwinding hit full speed.

Ben Bernanke repeatedly beat the drum that all of this is temporary so not monetization of the national debt. However, is that debt actually being "returned to the public through open market sales" if it is now being indefinitely rolled over by the Fed's member banks? Is the Fed splitting hairs.

Of course, if the "pause" of unwinding that the Fed is now talking about should become an "end," then the Fed definitely monetized that much government debt for good. That all depends on whether you continue to believe the Fed can and will continue to roll of that debt or whether it is already roiling markets so badly that it cannot be done. Many people now no longer believe the Fed will continue its roll off, as it appears unable to do so.

So, is the Fed monetizing debt—using money creation as a permanent source of financing for government spending? The answer is no, according to the Fed’s stated intent.... St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said: “The (FOMC) has often stated its intention to return the Fed balance sheet to normal, pre-crisis levels over time. Once that occurs, the Treasury will be left with just as much debt held by the public as before the Fed took any of these actions.†When that happens, it will be clear that the Fed has not been using money creation as a permanent source for financing government spending.

Again, that is only true so long as "intent" is actually carried out someday, and it is now looking increasingly doubtful that returning the Fed's balance sheet to normal is ever going to occur. I've always said the Fed's balance-sheet unwinding will be stopped short because it cannot be done, but that the Fed will be slow to figure that out. Due to its slow reflexes, the Fed will rewind its fake recovery right back into the same crisis it said it was saving us from -- ten years wasted for nothing, other than to become worse because the Fed enabled the mountains of debt to pile up Everest-high. Because there was never a workable end game, we are now seeing those stresses show up in all kinds of emerging troubles.

What the Fed funds rate is now revealing

What is now happening with the Fed funds rate is interesting to me because I ventured awhile back that market forces unleashed by the Fed's balance-sheet unwind (quantitative tightening) were forcing the Fed to increase its stated target for the funds rate just to keep up with where the market was leading interest, lest the Fed start to look like a joke. If the actual interest rate banks charge each other on overnight loans of Fed funds moves up faster than the Fed adjusts its target, that would make it obvious the Fed is losing control of its most basic financial tool.

We have Fed testimony showing it knows quantitative tightening can cause its target rate to rise above their stated target:

Officials have said that, as they drain cash from the system by shrinking the balance sheet, a rise in the federal funds rate within their target range would be an important sign that liquidity is becoming scarce.

We've already seen that happen as I reported in my last article, "Federal Reserve Confesses Sole Responsibility for All Recessions" and in the adjoining article to this one, "The Great Recovery Rewind: How the Federal Reserve's Balance-Sheet Unwind is Unwinding Recovery.") The Fed is now chasing its own unwind as it raises its target rate.

The Fed has now painted itself into a corner I've said was coming. It faces a conundrum because the Fed just stated this month that it now wants to back off now on its number of rate increases, but but its balance-sheet unwind is driving the rate up, and it cannot use its customary tool of buying US treasuries from banks because it is now trying to reduce its number of treasuries.

The Fed also can't buy treasuries back from member banks because that puts money in their reserve accounts, and the Fed wants remove money from the monetary system (tighten up the financial system). The member banks (all "national banks") in the Federal Reserve System are allowed to create money out of thin air just like the Fed by issuing loans against the reserves they hold in their reserve accounts. So higher reserves means they can more easily issue a lot more credit -- the opposite of tightening.

Because banks are allowed to leverage their reserves quite steeply (such as issuing seventy times more dollar value in loans than what they actually have in their reserves), they can create a lot of new money in the form of loans that become checks that are credited to other bank accounts and just keep right on moving all through the economy as fiat money. The Fed in its regulatory capacity determines how much banks can leverage their reserves to create money via loans in our "fractional reserve banking system," meaning banks only maintain a fraction of the money they loan out in their reserves. (See my article on the Federal Reserve System.)

So, one tool the Fed has for dealing with its conundrum is to change the ratio at which banks can leverage their reserves if the reserves are growing. This is known as the Fed's "Liquidity Coverage Ratio." Without this mandated ratio of deposits that get held in reserves to loans that are carried, banks would use their capacity to create money via loans to issue an infinite number of loans. They are restrained by having to raise capital and deposits in bank accounts and hold enough of that in reserves to meet their Liquidity Coverage Ratio.

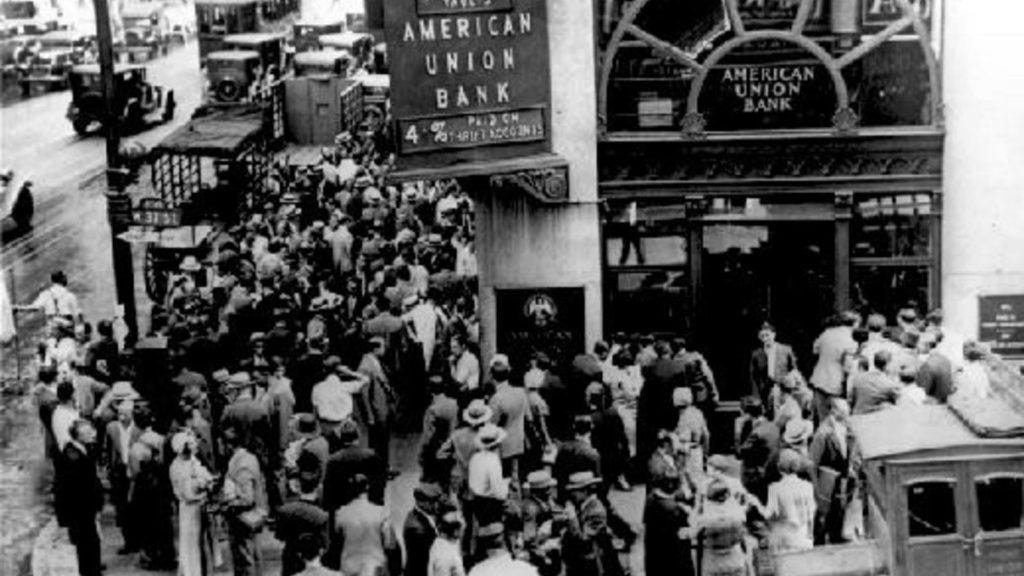

After the financial crisis, when there was a risk of runs on banks, the Fed changed that ratio to require the banks to hold more money in reserves in relation to the number of loans they hold as a regulation safeguard when the Fed was trying to avoid total economic collapse. Deposits, after all, are liabilities because depositors are guaranteed they can demand instant cash at will. Depositors get extremely unhappy if this guarantee is not fulfilled. That looks something like this:

And you don't want that.

All of this became too difficult to manage during the huge bond buying the Fed was doing during the Great Recovery. So, the Fed invented another tool to avoid having to manipulate the Fed funds rate that banks charge each other so that the rate stays within the Fed’s chosen range. In 2008 the US government approved this new power for the Fed, which allowed it to start paying banks interest on excess reserves (IOER) to entice them to keep more money in reserves than their Liquidity Coverage Ratio requires.

The Fed can use the IOER to give banks incentive notto loan their excess reserves to other banks, even as they keep those reserves up, because they can earn the IOER rate the Fed has set with absolutely no risk just by holding on to their reserves and collecting the Fed’s interest payments.

Since its creation, the IOER rate has been set at the top of the Fed funds target rate as a way to keep the Fed funds rate from exceeding the Fed's stated target for that rate. Now, however, the Fed funds rate is constantly pressing up near the top of that range, probably because banks are drawing down their reserves to buy and hold government treasuries, leaving them with less in excess reserves to lend to other banks.

The system is building up internal strains that are becoming harder for the Fed to manage, so it is always expanding its tools (a.k.a. powers). Now it is talking of lowering the IOER belowthe top number of the Fed funds range for the first time since the tool was implemented. That would make the Fed's member banks more willing to loan from their reserves since they won't be getting as much interest from the Fed for retaining those reserves, and that would keep the lid on the effective Fed funds rate. (More willingness to loan from reserves means other banks don't have to pay as much to get those loans.) However, doing that should also have the effect of draining reserves down faster, which seems quite a conundrum to me when the Fed is asking banks to keep those reserves up.

If the Fed doesn't lower the interest it pays banks on their reserves so banks have a little more incentive to loan to each other from their reserves, banks will likely raise their interbank lending rates above the Fed’s stated target range. In that case, the Fed winds up with a defacto interest increase in an environment so sensitive to increases that the Fed had to promise to keep interest from rising in order to save the stock market. The Fed will, then, will be seen as losing control over its fundamental interest rate, which will be highly disconcerting to all markets, not just stocks.

The IOER is a shadow taxpayer bailout

While the IOER's intention is not to bailout banks, it is a gift from taxpayers to banks; so I'm going to call it that, and here is why: That interest paid by the Fed to its member banks (which own the Fed as its only shareholders) is extracted from taxpayers in that the Fed's charter requires it to remit any "profits" to the US government. Therefore, paying out interest on all those reserves means less "profit" to the government.

The money the Fed remits to the government helps keep down the government's borrowing (or its taxes). With the advent of IOER, some of that money now goes to the Fed's member banks, which means it goes to CEO and executive salaries and bonuses and to shareholders as dividends, etc. With the increase in the IOER rate above the interest paid on regular reserves, much more of that money goes to member banks because excess reserves are by far the bulk of bank reserves ... as in about 90%.

Since much of the US government debt was financed with excess reserves, the interest the Fed pays out on those reserves is an occulted cost of government financing.

Is the Great Recovery Rewind monetizing the national debt?

Because the Fed remits its profits from interest on its securities to the government, the Fed has provided almost interest-free funding to the government as the government gets back part of the already low interest it pays to the Fed.

As the Fed now holds less of the government's debt, the government's net interest payments are going up because not just in the nominal interest it is paying but because it is getting less of its interest back. The Fed's member banks that hold government debt don't remit interest they make back to the government. Is this starting to sound like a game that is rigged at every turn to benefit banks?

The Fed's best option to get a handle on its new Fed-funds-rate conundrum is to stop tightening, but it wants to tighten. That is why Jawbone Jerome was neck-whipping quick (by the Fed's glacial terms) to start talking about slowing down the Fed's tightening, hoping mere talk by the Fed chair would ease markets (just as talk alone riled them up in the Taper Tantrum). Throughout the recovery, the stock market hung on the nuance of every syllable spoken by the Almighty Fed in whom they trust.

For the time, talk worked its magic again with stocks; but in the background the conundrum keeps festering in what appears to be an increasingly complex management problem.

Now consider this: if reserve balances of member banks don't come down, how is the Fed really bringing monetary supply back in line with historic norms? However, if it is quietly encouraging its member banks to use that recently new money supply that was locked up in excess reserves to buy and hold the government's new bonds (by having member banks buy and hold the bonds), is it not now indefinitely (maybe permanently) monetizing the national debt?

The Fed's argument against the claim that quantitative easing was a form of monetization was largely that QE was a temporary program that would be "unwound;" but if that really just means re-winding it around different reserve bank accounts, isn't it monetization because member banks continue soaking up the debt the government is refinancing to pay off the Fed? We all know the government has no plans or capacity to eliminate the monstrous debt it piled up during the "recovery" years.

I'm not exactly sure that is what is happening with the depletion of those reserves described in my last article, but even the Fed's own economist says the money for refinancing the debt is coming out of member bank reserves. If that wasn't so, the Fed's balance sheet wouldn't be shrinking. (Remember you have to take something off of both liabilities and assets to shrink the balance sheet. To call it a "balance" sheet, it has to stay balanced.)

I believe that, if banks don't soak up the treasuries by holding them, the Fed has to stop unwinding its balance sheet, or it will drive long-term government interest rates to dangerous levels. I think the bleed-down of reserves shown in my last article is sponge effect by reserve member banks, sopping up government debt as the buyer of second resort and, thereby, helping to suppress interest rates during the unwind.

I'm not certain on that, but there are a lot of pieces that we do now know that point to that, including statements by former Fed chairs about the Fed's plan to unwind its balance sheet:

Does this plan make sense? The answer is not clear cut, but based on the discussions at the conference, I’ll offer three arguments for changing course and keeping the balance sheet close to its current size in the long run.... Overall, I think the FOMC’s plan to return to a pre-2008 balance sheet and the associated operating framework needs more thought ... and some important arguments have emerged for keeping the balance sheet larger than in the past. Maybe this is one of those cases where you can’t go home again.

Gee, ya think?

Some of us have been saying since you started this plan, Gentle Ben, that this was always the real plan -- monetize the debt forever because you can never return home again. That, or as I have mostly been saying, the Fed just wasn't smart enough to see the the inevitable from the outset. You have two choices: blind stupidity or conspiracy.

Bernanke now argues for more power in the form of letting the Fed indefinitely maintain its higher balance sheet in order to have greater financial control over the economy. Always more power for the Fed, and crises certainly help the Fed grasp that power out of generally perceived necessity, lest the gargantuan banks that the Fed keeps making bigger fall on us.

(Although this two-part article series just covers the Fed's move away from rolling over its government securities, the Fed is also moving away from rolling over maturing mortgage-backed securities, which it buys from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which may be affecting the reserve balances of member banks. The amount of cash (as in dollar bills, five-dollar bills, coins, etc.) moving through the system also affects reserve balances. This article is complex enough that I chose not to go into any of that, but you can read more on that from the Fed here if you want more information.)