Shortages and Inflation Are Ripping the World's Face Off

The evidence that inflation is ripping everyone's face off is now widespread, and the situation is rapidly getting worse all over the world, making it harder for both US bonds and stocks to ignore it:

The US stock market took it on the chin again Tuesday, plummeting on worries about sustained high inflation that pushed bond yields higher.... The S&P marked its worst session since May, while the Nasdaq had its worst day since March. For the Dow, it was just the worst decline since last week's selloff.

It surprises me that, after months of inflation that haven't abated, I still have to argue with some people that inflation is hot and is not transitory. (Sometimes I even have to argue that it is actually happening, if you can imagine that.) Let me present some of the most glaring examples of inflation that is screaming like a banshee and clearly has been and will continue to be persistent.

September showed us that inflation is already biting into the belly of industrial sentiment and market sentiment. In terms of industry sentiment, a virtual conference earlier this month by Morgan Stanley with industrial CEOs, revealed a broad spectrum of Fortune 500 companies who say they are facing considerable strain in getting enough supply of materials and enough supply of labor and that the rise in costs that come with trying to overcome those shortages has become a serious detriment to business. Then you add to all of that their shipping troubles and rapidly rising shipping/freight costs.

Prices for many basic materials, such as copper and aluminum, are now at or near all-time highs, and industry leaders say they are passing these soaring costs along to consumers.

Commodities schmodities

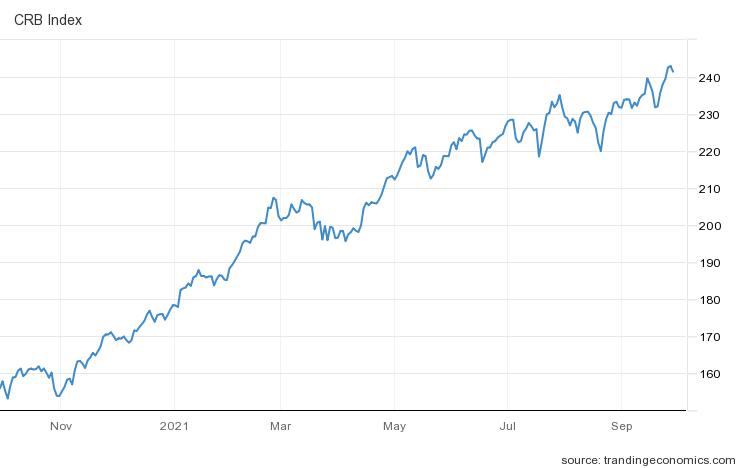

The lamest argument I battled earlier in year against the high-inflation thesis that I've bet my blog on was that inflation cannot be real because it is not showing up in commodity prices. Really? Take a look at the combined core commodities index (the CRB) for the past year, and how it supports what these many CEOs are now saying:

Anyone who thinks commodities are not reflecting inflation has been cherry-picking his commodities all year long! The commodities listed here are core commodities, and their aggregate average has risen a whopping 35% since the start of the year!

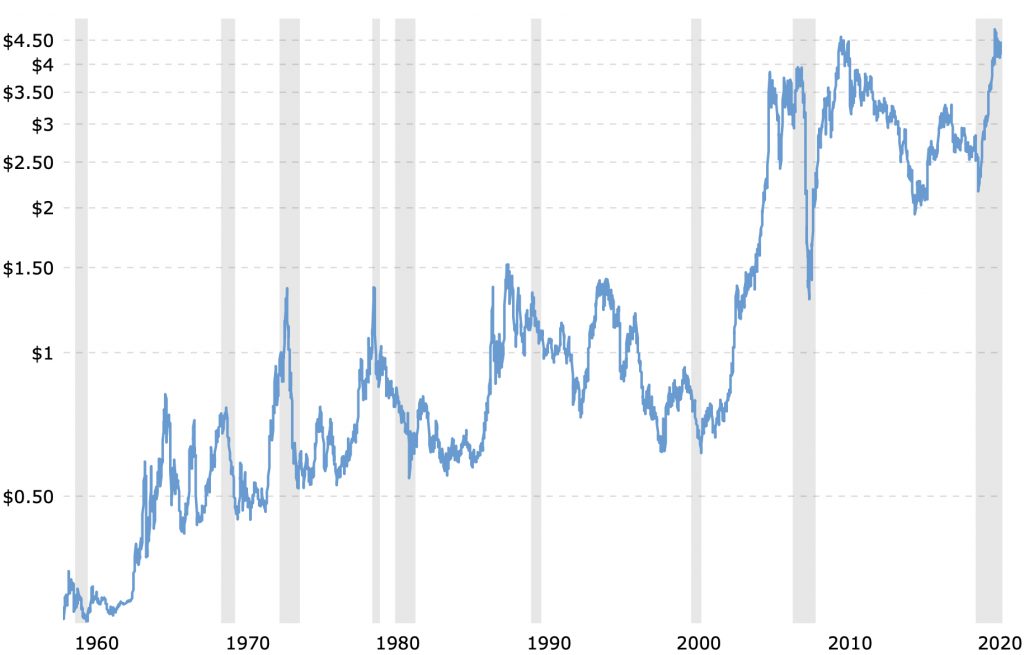

The oddest part of the rebuttal to my thesis is that some of the very commodities brought up by the limited few who seem to be baffled by commodities have been the ones that are inflating the worst! Here, for example, is one of the most-watched commodities for gauging inflation -- Dr. Copper:

Copper rose to prices that have never been worse!

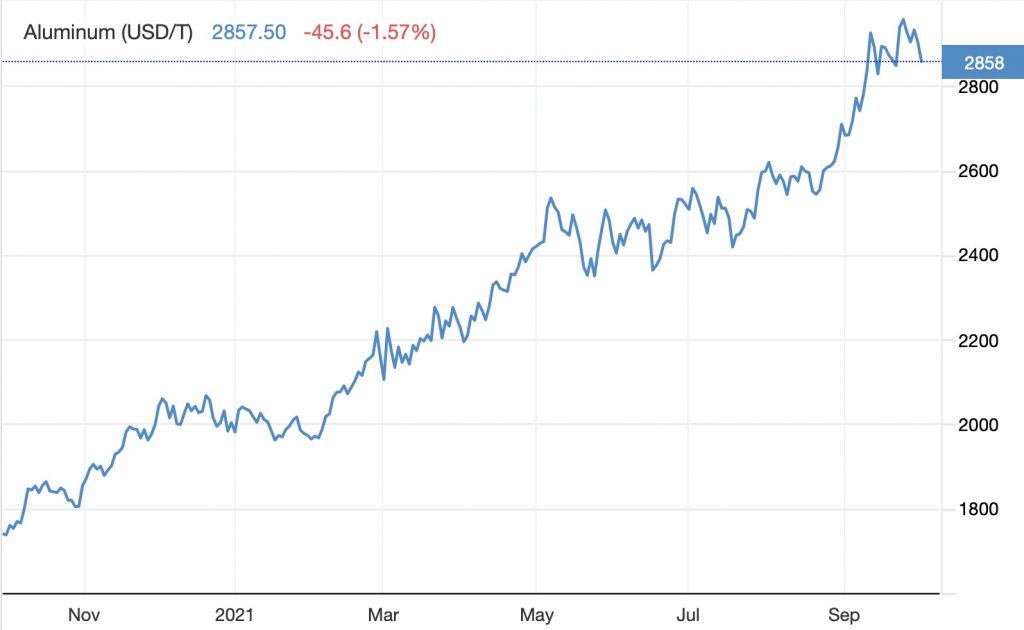

Now look at this year alone in Aluminum:

What? A 60%+ rise over the course of a year with a consistent trend line isn't enough to demonstrate the formation of high and persistent inflation with all the things aluminum goes into? Come on! What if I tell you there is only one time in history when aluminum priced slightly higher, and that the past year has shown the steepest rate of rise for a thousand-point climb or for any single year on record?

How much evidence from commodities do some people need in order to see that even their their old-school theories about inflation support a clear trend of high inflation in those commodities that go into everything? Since a few still hold to those dead arguments, I think they lack the intellectual honesty necessary to reach escape velocity from orbiting their own egos as is necessary for anyone to admit they were wrong about inflation or about it being "transitory." The Fed, of course, is one that has not been able to come right out and admit it was wrong, though it has, at least, given up its tired mantra of "transitory." To show you how persistent denial can be, just this week, I heard one person say he doesn't see inflation happening at all. All I could say was that his eyelids must have been Krazy-glued shut.

So, to peel back the glued eyelids, let me present more evidence of how persistent inflation forces have been, starting with steel since it, like aluminum, goes into so many products. Fortune noted last July that steel was already up more than 200% since the COVIDcrisis began, hitting a new all-time high, and asked "When Will the Bubble Pop?" By September 1, however, the bubble was even higher.

Take a look at rubber, which goes into many products. I reported back in July how rubber was melting on the hot road to inflation. As a result of rubber's rise, tires have been beating a rapid path up the inflationary road, too. General Tire, for example, has not been shy about raising prices. They raised prices 5% last December then 8% in April then another 8% in June and now another 8% in September.

And don't expect any support for the dishonest commodities argument against inflation from oil, the most important commodity in all pricing -- so important that I'll give it a section of its own:

Oiled up and ready to roll

Some people have argued that the present inflation environment is nothing like the stagflation of the 70s and 80s when I've said it is just like that period because "there is no oil crisis this time." I think they need to be a little less parochial and look beyond their own borders:

While industry-specific headlines have blared "energy crisis" for over a month now, the general public in the UK and other affected places are just waking up to the current energy shortage in parts of Europe and Asia. And many in the US haven't heard it is happening....

For those who can't see beyond their own horizons, here is a nice little comparison to the moves in natural gas prices now and in the 70s:

If you lived through the seventies, you might possibly remember these gas lines that went clear around the block:

No, this isn’t Venezuela. It's England. Take a look as hundreds of Britons line up outside of a gas station in West Birmingham as the nation faces a petrol shortage. #PanicBuyingpic.twitter.com/On2hZzsrMC

— Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) September 24, 2021

Only, as you can tell from the vehicles, those are gas lines in the 2020's in the UK.

While there is no basis for thinking we have to have an energy crisis in order to experience stagflation and a deep recession like the 70s (as if an energy crisis is the only way that kind of inflation can happen), it looks like we're going to get the energy crisis, too, just for good measure. (No sense leaving any trouble out of the mix.)

Rising natural gas prices also lead to a rise in the price of that horrible, non-green gas, CO2, because we source much of it from natural gas. That leads to a shortage in fertilizers for food. Because CO2 is also used for food storage in the form of dry ice, the rise in CO2 costs is adding considerably, believe it or not, to the shortages of food on grocery-story shelves. And shortages, as I've said throughout the time I've been writing that inflation and its effects will be the big financial story of the year, are part of the inflation formula I keep repeating of "too much money chasing too few goods."

As could be expected from a government official, the UK's Environment Secretary, George Eustice, assured his nation the present CO2 shortage will have little impact on food prices because food prices are already rising so quickly due to other factors:

He said that while food prices were increasing because of issues including oil prices and labour shortages, carbon dioxide was "a tiny proportion" of overall costs.

Leave it to government officials to not be able to think past their own political agenda. Better ask your local grocer -- or a farmer -- people who understand food pricing from the ground up:

The CO2 issue has caused a "big supply issue", one supermarket executive told the BBC. Grocery delivery firm Ocado warned it had "limited stock" of some frozen items.

Surely, "big supply issues" cannot cause rising food prices! Of course, you cannot expect an environmental secretary to understand economics, especially when he has a CO2 agenda to protect. Just as you cannot expect US media to print this information about the cost impacts of CO2 derived from natural gas when they, too, have a CO2/natural-gas narrative to push. So, some of our problems right now are government-created -- something I will go into in my next post, which will show how much we are doing to make these problems even worse.

It turns out the CO2 shortage due to the extreme rise in natural gas costs (equally due to gas shortages) may even broaden the energy crisis in the UK beyond petrol and natural gas prices:

The Times reported that ministers were concerned that six reactors might have to close because of the [CO2] supply problems.

Nuclear reactors without CO2 for their cooling systems go boom if you keep them running.

The current energy crisis and resulting food shortages are by no means constrained to Europe:

CHINA ENERGY CRUNCH: The electricity shortages in China are worsening, and widening geographically. It's getting so bad Beijing is now asking some food processors (like soybean crushing plants) to shut down | #OATT #China #EnergyCrunch with @cangsizhi More on @TheTerminal

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) September 24, 2021

What do you suppose happens when a nation with billions of people to feed runs low on food and needs more energy to grow, process, store and ship that food? What happens when they are competing against Europe where the same shortages are already coexisting? What will happen as the world's largest economy joins that competitive crush?

Does that sound like "transitory" to you?

I am beyond certain that the Fed is completely out to lunch on this, and, as a result, the price of lunch is going up even more for everyone.

Maybe some more pictures will help convince those who cannot see what is about to be passed through in consumer inflation because it is already throughout the production and storage pipeline:

Kind of like the highest natural gas prices in ... forever.

Of course, besides production and storage, there is also that whole shipping problem that I've been regularly covering as a major contributor to supply shortages and inflation. Some of the same ports that are clogged with container ships because nations have shut down ports due to COVID also handle tankers. As I've said all summer, the supply-side contribution to inflation from the shipping logjam is certainly not transitory in the respect that the Fed intended you to understand "transitory." It has only gotten worse all summer long. It is transitory only in the sense that, like all things, it will eventually end. It's probably not eternal. Few things are.

But also don't think the energy crisis in Europe (soon to come to a shore near you if you don't live near a European or Chinese shore) is relegated to just petrol because, remember many electrical generation plants run of natural gas or diesel and then there are those darn reactors. As a result, electricity prices in parts of Europe now look like this:

What happens when winter hits?

Those electrical prices are not only higher for consumers at home; they means the products they are about to buy, being made with that electricity will be higher, too, if they ever arrive at port or escape their containers in port. And you cannot say, "Well, that's only France." Remember Texas a few months back? California? Nothing has been done to correct the problems that caused those massive electrical price increases and brownouts.

Could be a cold winter in Europe.

Could be a cold winter in the US, too, as shortages in a desperate Europe and China lead to increased exports of crude and its byproducts from the US, forcing domestic prices to compete. This story is only just getting warmed up.

Inflation will soon get a raise

While wage inflation has been noted throughout the last several months of this year, it has finally proven it is definitely not a transitory factor. Obviously, wages that rise are not inclined to come down easily, so I'm not talking about that well recognized reason that rising wages are not a transitory force for inflation. I'm talking about the excuse used all along for discounting wage inflation, which was that, when all the government augmentation of unemployment benefits ended, the vast horde of unemployed would finally go back to work, so pressure on wages would go away.

Au contraire.

It ended, and they didn't. One reason may be that, for many, those unemployment benefits were replaced with semi-universal basic income in the form of government payments per child for those with children, which isn't about to end.

Wage inflation is particularly sticky, which is why policy wonks, who wanted to sell their massive corporate tax cuts after they became law (to make them easier to defend down the road), convinced corporations to give one-time bonuses to assuage the masses, not wage increases. That happened because most of the tax cuts went to dividends and stock buybacks, as I argued they would, and, thereby, made up for the Fed's tightening for awhile so that stocks kept climbing on this replacement fuel. A number of corporations did give one-off bonuses of $2,000 as window dressing to placate the dwindling middle class. If they gave it as raises, they'd be stuck with paying sharing the money for years to come.

However, a new day has dawned for labor. Workers feel empowered by the past year of enhanced unemployment benefits and by gains they made from retail investments in stocks, so the wage-raise train is now coming into the station.

Many boomers also retired early, and others still don't want to come back due to COVID concerns, which leaves the labor market in extended short supply, regardless of unemployment benefits, giving more leverage to the younger of the generationally-defined people groups.

Here is what happened to the baby-boomer work force as soon as the COVIDcrisis hit:

They ran from the labor force and retired. Being over 65, it is safe to say almost no one who was part of that huge surge in retirees is coming back.

As I said near the start fo the COVIDcrisis, we'll only know the economic damage from the forced COVID closures when we find out months down the road what didn't return after the economy reopened. We are now there. The knowing is upon us -- those laborers above being one example of what is not coming back on.

Major shutdowns work like this as an analogy. A well-known with shutting down a large factory is that not everything starts back up. That is even more true when shutting down a large national economy. More so yet, when shutting down all large economies around the world. Not everything that gets turned off with a switch comes back on with a switch.

The above graph represents a permanent change in the labor pool. These retirees were going to quit, regardless, but the COVID closures brought many retirements forward in time all at once, making COVID an accelerant for an already growing demographic problem.

Rising wages have always been one of the most problematic causes of inflation. While they are great for workers, a good part of the increased labor costs does get recycled back to everyone. That cycle keeps getting priced in as further wage increases to keep up with the cost of living, causing more future inflation. It's a tough cycle to break, making it one of the most persistent causes of inflation once the cycle begins.

The most successful way corporations have fought wage inflation has been by outsourcing US jobs to other nations. Not only has that become increasingly unpopular in both parties (deservedly so in my opinion), but it has become increasingly difficult to pull off now that shipping lanes are jammed up due to port closures. Supply lines have busted to pieces causing many corporations to rethink their outsourcing because factories in other nations are sporadically shut down due to COVID. Trade with some regions is sometimes banned due to COVID concerns and in some places curtailed by the leftover impact of trade wars. Outsourcing labor is simply not the breeze it once was.

Millennials and Gen Z are also looking for new options. They have different core values, such as being able to work from home, which corporations are having to adapt to. Working for companies that are environmentally friendly, for example, is a larger core value, and that is not something some companies can due much about.

These are all demographic changes that are not going away as a result of reopening. The decades of low wage increases (and therefore low inflation due to low wage pressure) may have ended with COVID as the catalyst for change.

Housing inflation about to raise the roof on CPI

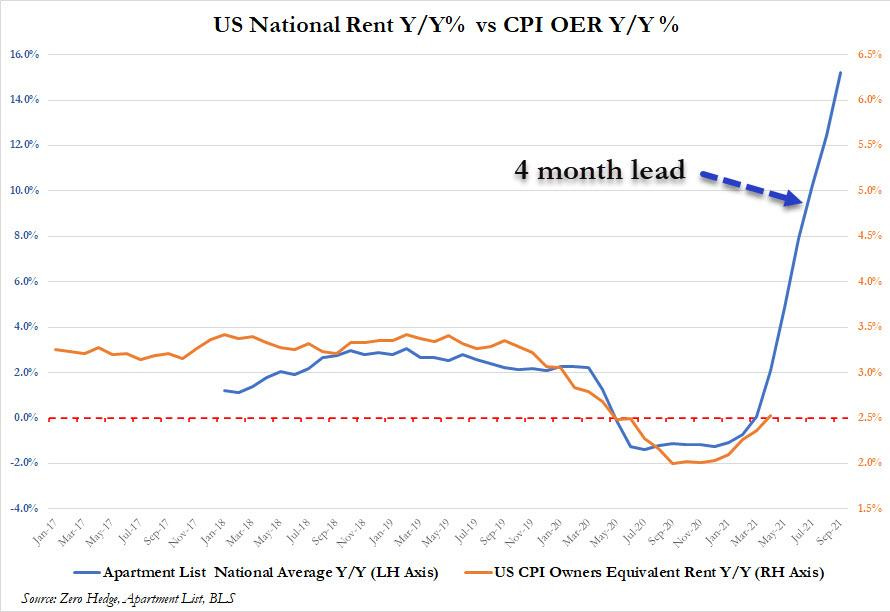

While housing counts for about 30% in the consumer price index, it has barely begun to show up in the official CPI numbers because it is based on homeowner guesses about equivalent rental rates, not actual home prices, and it is inputted in a way that causes a large lag time. According to Apartment List, rents this year have gone up nationally by 16.4%, and they are still rising faster than they rose before the pandemic, but CPI reflects very little of that ... so far.

You can see in the graph below how CPI's category for housing prices (Owner Equivalent Rent -- OER) tracks with actual rental rates with about a four-month lag time. You can also see how much that means OER has yet to catch up with where rents have already gone over just the next four months:

That is rental inflation that is already in the bag, not projected, but it is not, yet, factored into CPI, misleading us to believe inflation is lower than it really is. It will be. To some extent, the government will likely find ways to "adjust" the numbers down with seasonal excuses, etc.; but they won't be able to adjust them as much as they are about to rise and convince anyone they are doing anything other than lying. So expect the official CPI numbers to start catching up over the next four months.

Moreover, at a time when rents typically drop due to seasonality,

rents are continuing to grow at an unprecedented rate.

And, in spite of rental forbearance on rents making it hard for landlords to raise rents on existing renters,

2021 has brought the fastest rent growth we have on record in our data.

While the end of mortgage forbearance, which Biden extended until the end of this month, may bring home prices down as foreclosures start to appear and add more inventory to the house market, the new rules for foreclosures coming out of forbearance require banks to wait ninety days to start a foreclosure and require them to ascertain any house being foreclosed has been vacated before starting. These rules remain in effect until January 1, 2022. So, relief for housing prices will not come in time to make any difference on what is already waiting in the pipeline to be reported as establish inflation facts for, at least, another six months.

It is also possible that most homeowners will become more aware of the rise in housing costs as they refinance at the end of forbearance and start giving higher estimates to the BLS as to what they estimate their house would rent for. Part of the lag between actual rent increases and CPI is due to how long it take homeowners, who are not paying rent, to realize what is happening in rents around them, which they never do, as a group, fully realize.

It is also reasonable to extrapolate that those owners who do not come current on their mortgages and who are eventually forced out of their homes will increase rental demand, pushing rents even higher even faster.

Even if none of those likely possibilities play out, one thing is certain: the past four months of rent increases were the worst by far, and they are just about to start getting reported in CPI in the months ahead, and rents are still rising twice a quickly as normal.

Oh, but it gets worse, rental forbearance, extended illegally by President Biden according the Supreme Court, was struck down by the Supreme Court at the end of August. The evictions that will come from that have not even begun to happen, and those evictions will force renters to find rentals elsewhere, now at much higher prices. So, at about the same time previous homeowners are looking for a place to rent evicted renters will be looking for a place to rent.

How can forced evictions not push rents up? Rents were effectively frozen for those who chose to enter forbearance because raising rents during forbearance would have just resulted in more renters choosing forbearance. For landlords that presented a high risk of getting no rent at all if they tried to raise rents on existing renters, so new rents would have tended to rise only for new renters. As evictions again become possible, that constraint will fade away.

We're talking millions of people who will soon be emerging from these protections. To be sure, all of this will be mitigated by future government programs intended to soften the damage with bailouts, etc.; but not all of those intentions will make it through congress, so all of this represents higher upward pressure and turmoil for months to come. It's just not clear at what level or with what timing it will all play through as the government continues to try to find ways to delay it all.

Much interest in higher interest

Years of extremely low interest rates set by central banks all around the world have enticed nearly everyone and every corporation and every government into extraordinarily high debt, far beyond any historical norms, and now interest on treasury bonds is rising, and that affects interest on home mortgages. Once the Fed starts actually tapering its own bond purchases, that's not going to go well.

The Bank of England has announced it will soon start moving its targeted short-term interest rates up for the UK. The European Central Bank has said it will taper its purchases of securities, creating an environment that is sure to raise rates. These two have merely gotten a slight head start on the Fed, which has more than strongly indicated it will taper security purchases sooner and raise interest rates sooner than it had indicated back in the days when it claimed inflation was transitory. The Fed has started to backpedal on its earlier claims with statements like "not quite as transitory" or Powell's most recent statement before congress:

"Inflation is elevated and will likely remain so in coming months before moderating."

"Transitory" has subtly shifted to "is elevated and will likely remain so." An indiscriminate number of months is, of course, safe. "Months" can easily become twelve months, and a year can become two, so let's focus on "elevated and likely to remain so."

In fact, Powell even added,

"The supply-side restrictions that are so much at the heart of the inflation we're seeing … in some cases they've gotten worse."

As I was saying they would from the time the Fed started making its "transitory" argument,.

As I wrote on Monday, the Fed's hints now at moving forward its bond tapering and interest hikes (actual tightening of monetary conditions) were already causing a daily anticipatory rise in US treasury yields. I referred to it as an anticipatory foreshock in the stock market. A much larger shock came less than twenty-four hours after I published that on my blog. (See "Stocks and Bonds Starting to Tussle.")

These bond rates will likely ebb and flow as we remain in anticipation mode about when the Fed will actually start tapering and how quickly and because the Fed still wholy owns the US treasury market until such time as it does taper, so it can reset rates where it wants them. Tapering means giving up that direct market bond-market interference.

Another argument against my high-and-persistent-inflation thesis has been that the US dollar is not falling in value on the dollar index. In the present environment of global economic self-destruction that old-school thinking doesn't apply. The US dollar is measured in the dollar index relative to other currencies, so whether it rises or falls says as much about the rest of the basket of currencies as about the dollar.

Now that the Fed has joined the currency chorus in spirit with Europe and the UK, the dollar's value has actually strengthened against those other currencies because raising interest rates increases demand for the dollar, and the Fed's slowing of its treasury purchases will effectively raise interest on bonds because the government must attract other lovers who will not be as loose the Fed. Back when it appeared the Fed would be slower than some central banks to taper its bond purchases and to raise interest rates, the dollar was falling against those currencies.

It is now anticipated that European inflation will come in for September at a 13-year high. In the US it is already much worse than a mere 13-year high.

Sentimentally speaking, breaking up is hard to do

My claim for the past year has been that inflation will rise so high and so long that eventually it will kill the stock market bull (i.e., will cause, at minimum, a 20% crash into a bear market, though I think it will eventually be down by more than that). It will do this one of two ways by impacting investor sentiment because it forces the Fed to tighten sooner and harder (as we're starting to see), or it will kill the stock market bull by killing the economy all around it with crushing cost increases (as we are also seeing). The longer the Fed delays its tapering, the more inflation will accomplish the latter. The Fed easing, instead of helping the economy at this point is killing it with kindness, making it easier for workers to stay away and easier for everyone to bid prices up on short supplies. The days when the Fed can help with loose money have finally reached their natural end.

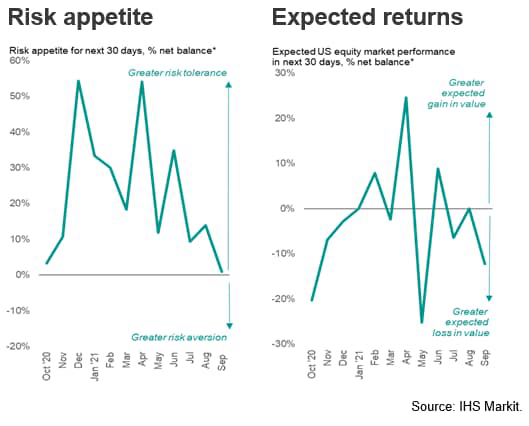

We can now measure just how much these inflation/tapering concerns are starting to eat into the soft underbelly of bullish investor sentiment. IHS Markit presents the following survey:

This comes from investment managers' statements about their own (and their client's) sentiment.

The darkening picture of market sentiment is signaled by IHS Markit's new Investment Manager Index (IMI) monthly survey, based on data from a panel of 100 institutional investors employed by firms which collectively represent approximately $845bn assets under management.... However, recent months have seen the survey indicate a cooling of investor sentiment from peaks recorded earlier this year, with strong risk appetite seen in prior months almost evaporating in September, accompanied by an increasingly bearish near-term outlook for equities.... The survey's Risk Appetite Index fell from +14% in August to +1% in September, barely above the zero level that separates risk tolerance from risk aversion.... At the same time, the survey's Expected Returns Index fell from zero in August to -12% in September, meaning more investors see returns falling in the next 30 days than anticipate a rise.

As a result of waning investor sentiment, the stock market has refused to close north of SPX 4600 for almost a month now. It has made significant efforts twice since the start of the month to recover its previous high around 4550 and has failed well short each time. During this time the main debate in financial headlines has been over how quickly rising inflation will force the Fed to start tapering its high levels of stimulus and to tighten interest -- the very thing I said many months would come into serious play against the market for the simple reason that inflation would not let up until it did. While all that seems obvious now, just remember it was far from obvious when I bet the continuance of writing for my blog on it. Nearly everyone was parroting the Fed's words about inflation being "transitory," but I've held to my guns.

The stock market and Fed largesse during the COVID period have remained nicely married:

Their breakup will not be so nice.

The environment we are facing is not a very pretty one. The world is in substantial disequilibrium. Markets are in various states of distortion all over the place.... Global debt has grown massively. One reason: the largess of the Federal Reserve System. It is hard for anyone to see how we can grow our way out of this burden.... So, the stock market did not have a very good week. Maybe there is a good reason why it did not.