The Big Changes in Central Banking are Already Here!

It's time to close out the topic I've run with for this year on central banks and their creation of digital currencies (CBDCs). I believed 2020 was clearly going to be the year of the advent of CBDCs, which is a monumental change in money, and it did turn out to be as China launched the world's first CBDC this year. Others are rushing to follow.

So, let's close the year by bringing all of that up to date and end with where the big banks are likely to go from here.

The simple ABCs of CBDCs

CBDCs are clearly part of the picture for 2021 as other central banks will likely be coming online with their own competition to China in the coming year because they see China as hoping to use its advantage of being the first central bank digital currency to spread the use of the yuan globally. It is, therefore, likely some central banks will rush to fill in the gap so China doesn't penetrate their digital currency "market" before they do.

The Fed, on the other hand, has consistently showed all year that it trusts in the clout of the dollar, so is taking a slower more methodical approach of letting other CBs be first to initiate digital currency so the Fed can observe the pitfalls and make a steadier launch to preserve their reputation as being the most stable bank in the world. So, don't expect a rush from the Fed this year. However, by year end in 2021, we may be talking openly and publicly about the Fed's schedule for an actual CBDC launch as more than just a project goal.

Short and sweet: they are here and every central bank is going to be doing them within a couple of years.

Hyperinflation risks are rising

This is the first year since the year when I started this blog where I've been warning to keep a watch on inflation. I'm still not saying it will happen, but the move of CB finances directly into the pockets of Americans, as happened with the latest round of stimulus checks, can cause that inflation if the money added to the general economy exceeds the money lost due to unemployment, lack of sales etc.

The recent explosion I wrote about of money moving from the broad class of M2 into the most liquid cash (M1) heightens this risk a lot. So long as money remained in US treasuries (M3) or other bonds or stocks, there was almost no risk of inflation in the general marketplace.

We could also see shortages of goods and services due to the move back into economic lockdowns. Too much money chasing too few goods or services is the prime formula for general price inflation.

That works like this:

As small- and medium-sized businesses stay closed, real output will decline. Without real output, efficiency in the economy will deteriorate and inflation will soar.

Simply put, if people are flush with cash, as now appears to be the case for many who are doing better off of unemployment plus UI supplements plus stimulus checks plus forbearance than they were before the Covidcrisis, they will bid prices up to get their hands on the depleted output of the nation. The continuing trade wars also make that shortage problem worse.

It will depend on the balance of how many people are doing better off with all the stimulus and forbearance and how many are worse off. If there is a shortage of money, prices are not likely to rise much, even with a shortage of goods, because people simply can't pay the higher prices. You can't squeeze blood out of a turnip.

So, we're watching a dynamic equation here where demand is moderated or amplified by supply of cash and faces off against possible shortages of goods or even services (with some service businesses in lockdowns and others already broke and out of business from earlier lockdowns).

Are there signs of inflation?

Inflation did heat up in the summer, but this was just making up for the drop in inflation that happened during the spring lockdown. Prices really just started rising back to toward trend:

That rise tapered back in the last couple of months, which came in around 0.2% month over month. Food prices saw the sharpest rise (about 0.4% month on month during the summer, but that makes sense because people people were likely replenishing food stocks after the lockdown when they didn't go out as much to buy food and lived off their household stores. The return to shopping would have created pressure for prices to rise because supply of some products came up short (due to producers shut down during the lockdown and exports cut off during the international transportation quarantine).

You may recall meat processors shutting down. That resulted in meat prices rising the most (as much as 14% YoY). That shows you the shortage side of the dynamic equation I just described. Fruits and vegetables went up 5% YoY, which surprises me, as there seemed to be no shortage of those throughout the political season.

Prior to summer (during lockdown), household paper products shot up:

Again, no surprise, remembering those toilet paper lines and battles. So, you can see the greatest mover of prices is really supply. People won't bid up prices just because they have buckets of money if supplies are plentiful. Why would they be willing to pay more needlessly when retailers have every reason to fight stiff competition on the supply side?

That's where my gold boomtown example comes in. There you have huge amounts of money and very limited supply because you are far from industry and commerce. So, an apple jumps to $5, and the people provisioning gold miners make more than most of the gold miners.

Forces fighting inflation

Lance Roberts has pointed out "Five Good Reasons the Fed's New Policy Won't Get Inflation."

To sum them up with brief commentary:

The entire premise behind the Fed’s “new policy,†and by being extremely vague about it, is to allow the Fed to maintain, and engage in, “ultra-accommodative†policies without any real limits. However, as shown below, the Fed’s monetary policies have not been successful at creating stronger economic growth or inflationary pressures.

It's true the Fed couldn't get it (inflation) up to save their impotent souls, but this time really is different. The difference is that, as we all knew, the Fed spent the last decade creating all new money inside of its member banks with the purpose of "creating a wealth effect" by pushing up stock and bond valuations. It didn't do much for the economy, but it did a lot for bond prices and stock prices.

Money inflates where money goes (talking price inflation, not the inflation of money supply, but that would be true also). The reason is simple: Money only inflates prices where money goes because money supply actually only inflates where money goes. The difference this year is that the Fed's free money, at the impetus of the federal government and with the federal government's full involvement started pouring directly into the hands of consumers.

What the Federal Reserve has failed to grasp is that monetary policy is “deflationary†when “debt†is required to fund it. How do we know this? Monetary velocity tells the story. “The velocity of money is important for measuring the rate at which money in circulation is used for purchasing goods and services. Velocity is useful in gauging the health and vitality of the economy. High money velocity is usually associated with a healthy, expanding economy. Low money velocity is usually associated with recessions and contractions.†– Investopedia

There you can see that during the past decade when the Fed massively expanded its balance sheet to add money into the economy, the velocity of money fell ... and then fell off a cliff in 2020. The results was we had very little inflation throughout that period and some deflation during the crash, even as the Fed rapidly expanded its balance sheet at a faster, higher rate than ever before.

This is just a fancier way of saying what I was saying above. Right now the velocity of mony remains low, so that means all that new M1 cash I've written about this month is pooling somewhere. It is not circulating in the general economy. It may just be waiting to leap into stocks and scoop up bargains at the next crash, or it may have been readied for paying backed up mortgages and rent if the new COVID aid bill did not pass. In which case, it will likely move back from M1 into the broader M2 class (term savings, etc.).

If it moves into the general economy, however, expect some inflation.

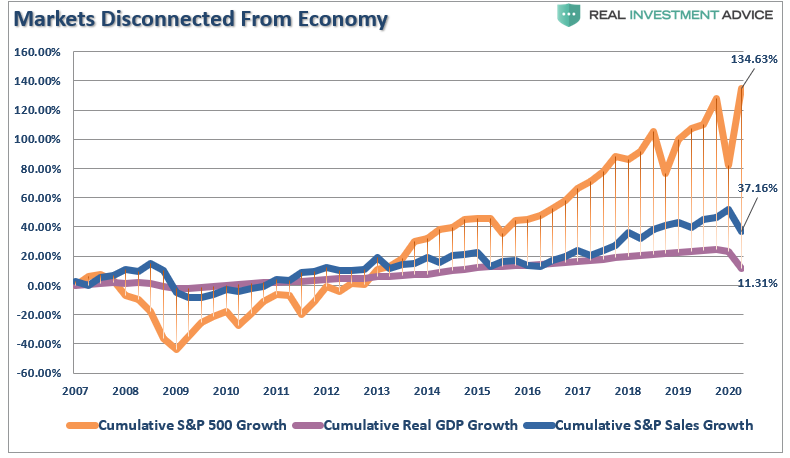

Roberts notes that, because all the money kept recycling in the speculative stock market, that's the only place it drove up prices. Because that is asset prices, everyone wants that kind of inflation. However, he also notes it did not help the general economy much at all:

As an economic recovery plan, it was a bomb. Fully believing it would be is why I started writing this blog in the first place.

Unfortunately, the “wealth effect†impact has only benefited a relatively small percentage of the overall economy. Currently, the Top 10% of income earners own nearly 87% of the stock market.

That, too, is a point I have been harping on for years. The Fed is only capable of helping people invested in stocks or bonds. The money never trickles down. The closer you are to where the money is going (stocks) the better you do, but the bottom 50% don't have enough surplus money to put it at risk in a speculative market. They don't even have enough to put it in stocks if there were very little risk. After all, much of America only had about $500 extra in the bank when the COVID crisis hit. When you're running month-to-month like that, you're not likely to speculate in stocks.

A point Republicans cannot believe is that, since Ronald Reagan's shift to supply-side economics, nothing has trickled down to wage earners, but here is the truth:

Since the money pouring in stocks didn't trickle down to any real rise in wages, other than regular fluctuations with the business cycle, it created no significant inflation. Reagan's lowering of the capital-gains tax rate caused an endless recirculation of money within stocks. Why would you invest in other things when you get the best tax rate by purchasing existing stocks and selling them over and over again?

Higher wages lead to increased consumption which allows producers to increase prices (inflation) over time. This has not been the case for nearly 40-years as technology continues to reduce the demand for labor by increasing productivity. This is the “dark side†of technology that no one wants to talk about.

Well, that, and allowing illegal aliens to keep pouring into the country to maintain a true peasant work force and allowing jobs to keep pouring out of the country with the free importation of goods made from those jobs back into the country -- something Trump has tried with partial success to put an end to.

[Inflation] cannot be achieved in an economy saddled by $75 Trillion in debt which diverts income from consumption to debt service.

Why, because increased debt service means much of that new money just endlessly goes back into servicing the astronomical debt. So, it, again, stays in banking circles.

The problem for the Federal Reserve is that due to the massive levels of debt, interest rates MUST remain low. Any uptick in rates quickly slows economic activity, forcing the Fed to lower rates and support it.

Those are the places where Roberts agrees with me. Where he differs is with my belief that pushing money into households so that it does enter that spending cycle may cause inflation.

Why Sending Money To Households Won’t Create Inflation

If the Government keeps sending money to households, it is going to create inflation. Such is the underlying sentiment behind a universal basic income and its impact on economic growth. Unfortunately, it simply isn’t true.

I don't see why that is unfortunate. I certainly hope it doesn't create inflation, but I am concerned it greatly changes the chemistry by bringing velocity to money sent to those households. We'll see.

The Federal Reserve’s new policy tool is nothing more than a “do anything†excuse. The reality is the Fed has no actual ability to create employment, control inflation, or create economic prosperity. The only thing they do have the ability to continue to create is the “wealth gap.â€

And, on that, we are back to agreement.

We're all Fed up

The only reason the Fed has been popularly viewed as a bold success is that it has hugely inflated the stock market for a decade, but that hasn't helped most people at all. And even those who have seen their 401Ks helped will be left helpless if the market crashes and their retirement funds are erased. I'd rather see a stock market built on real economic growth and genuinely healthier business activity, then it would have a real foundation under it.

It's fair to say that the current mentality present in capital markets is not simply abnormal, it's one that resembles a full-blown mania.

Full blown mania's pop just like I've been saying this one could real soon ... again.

We appear to have entered stagflation, which the Fed has no means of alleviating. It's pretty clear that debt is choking corporations and consumers.t

We cannot lower interest more even to try to stimulate the economy with more debt. We're sitting on the floor. Nations that did move into negative rates remained stagnant, and bizarre things began to happen in their financial realms ... like people getting paid to buy a home by the bank dropping their mortgage balance by more than their payment each month.

That's why the Fed has decided it's not going further down interest-rate rabbit hole into Wonderland -- something I've said these Patron Posts it would be loath to do, even as others were saying it certainly would. It's got the pedal to the floor on money creation, but unemployment has stopped improving about halfway back from the enormous pit we fell into this year. We're spinning our wheels at this point and getting nowhere. The Fed's largesse has undoubtedly eased the pain for many but the recovery has stalled.

Here is where the Fed puts the labor-force participation rate:

Halfway back to our drop-off point, and no longer improving. Do you think it is going to improve with COVID closures back on the rise all over the nation? (Whether you believe in COVID or not.)

Meanwhile, the Fed is already having to choke down more and more of the US debt as fewer and foreign buyers want it in a rapidly worsening death spiral.

China is especially dumping treasuries. Why wouldn't it? As mentioned earlier, China wants to establish global financial dominance of the yuan as it introduces its CBDC, right now in China, later to the world ... if it can; but it also has no surplus to invest anymore and much less need for treasuries. Treasuries are often exchanged due to trade. Fewer Chinese businesses trading with the US during the trade war means less need for the Bank of China to do foreign currency exchanges via treasuries.

With the government spending more and more in COVID relief, the Fed is bailing it out as quickly as it can. In the last twelve months, the Fed has doubled its holdings of US treasuries (a $2.4 trillion expansion) because there are not enough other entities to sell to and still keep the interest rate down where the federal government needs it in order to continue to manage its chasm of debt. The Fed's share of the US debt has nearly doubled in one year.

With foreign interest in US treasuries fleeing, the codependency between Fed and feds has not been greater since WWII.

The federal government had to start off 2021 with helicopter money going into US consumer banks accounts during the final few days of 2020. That's not an auspicious beginning when the nation's central bank is already choking on US debt.

The question of why anyone still pays taxes in a time of helicopter money, when the Fed simply purchases whatever debt the Treasury issues, remains.

Which, of course, will increasingly be the political argument for expanding our move into MMT, which has already begun.

Thus, the big changes in central banking are already afoot. Movement to CBDCs is a way of following the COVID trend toward working virtually and living digitally. A Fed CBDC will eventually be a convenient way for the Fed to put MMT money into modern consumer pockets to juice the Main Street economy directly. With the rounds of COVID relief via helicopter money, as went out again this week, we've already taken a baby step into MMT because foreign nations, foreign companies, and foreign individuals certainly are not picking up the US government's extra debt for those programs. It also means we've already taken baby steps into Universal Basic Income.

I imagine people will get used to this aid and expect it to continue now that they see it can happen and like it. Try pulling the pacifier out of the baby's mouth and see what happens. So, expect 2021 to be the year where the baby learns to walk with Father Fed holding her hand.