This Economy is Ugly in its Bones – Part 3

Suffering inflationary heat stroke

While we all hope the inflation rate won't rise further, an inflation rate that stagnates right where it is today is like the sun hitting its zenith at noon. The sun may not get hotter as it now slowly slides lower in the sky, but it keeps baking the earth around you, making all of it more insufferable for hours beyond its peak. The hottest temperature in the day usually comes around 4:00 because the earth keeps absorbing more heat.

When you hear people arguing that inflation is peaking, it's almost a meaningless as saying "It's noon, so the worst heat is over." While I think it is not even yet noon, and inflation will still push to higher numbers, the CPI headline rate will have a more difficult time climbing higher now that we are comparing year-on-year to months where the inflation rate of rise was starting to increase; but the rate moving higher becomes almost academic if "peaking" merely means we have the equivalent of hours of scorching sun remaining in the hot afternoon -- only our hours with inflation are months long.

The compounding effect of inflation, like that with the accumulating afternoon heat on earth, makes inflation worse even if the headline number doesn't rise any higher, but just keeps cooking you at the same rate of rise. Today's 8.3% is compounding the inflation already baked in from last year. I know that's a statement of the obvious, but you'd be surprised at how rapidly that accumulates on your suffering index.

For example, when the earth's temperature rises 8.3 degrees from 90 degrees at the time of your late breakfast on the lanai to reach 98.3 at noon when you are out gardening, it becomes hard to bear. You will feel done for the day, whether the gardening is done or not and will be glad have your lunch and iced tea. However, if that same rate of rise continues over the course of the afternoon and accumulates to 106 degrees, it becomes insufferable. If you didn't quit gardening at noon, you'll probably pass out from heat stroke in the afternoon. The sun's temperature certainly didn't change in that example. The rate of rise on the earth around you remained constant, but each additional hour at that continuous rate of rise starts to feel deadly.

So, even if the minuscule dip from 8.5% to 8.3% was not just a waver along the path up, the heat we keep accumulating at that rate will be sunstroke by high tea. (That's 4:00 if you're British. I always wondered why but perhaps it is because that is the high temperature point of the day, even if not the high point for the sun. It's the time when you most need to cool off.)

Let me give you a pictorials example of what happens when inflation keeps climbing and compounding at for years:

This gives you a sense of how the accumulative effect of inflation over for a number of years when it becomes hard to wrestle back to the ground, as was the case in the seventies, can become quite astonishing. At these kinds of steep climbs, each year out extracts a lot more volume from your bank account, especially visible when you look at CPI gain as the index's point value and not just the usual up and down line of its percentage change from quarter to quarter.

Manufacturers are burning up in the afternoon sun

One of the ways I was able to point out in these Patron Posts that inflation was the most important thing you needed to start keeping your eye on before it even appeared -- because it would transform the financial landscape and crash markets and the economy -- was by looking upstream to the headwaters from which all inflation flows before you feel it coming. One of those channels is looking to the cost increases manufacturers are experiencing.

A year-and-a-half ago, it wasn't hard to predict higher inflation would arrive on the consumer side that way, though surprisingly few saw it coming. Today, one can just as easily predict inflation is going to continue to heat us up by looking in that same direction. In fact, I think the inflation rate will go up, too -- not just that the same rate will keep cooking us.

At the start of the month Wolf Richter reported, "Inflation out of control;" "it has not peaked, but Intensified†amid "strong demand, shortages, and lengthening lead times."

When I hear the "maybe inflation has peaked" argument by the mainstream financial media, I have to think those saying it have already spent too much time in the sun without their hats on. How can the inflation rate possible have peaked when the manufacturing side is experiencing major rate increases it has not even passed on yet?

For instance:

Inventories of manufacturing input materials in April rose quickly as producers hoarded in the face of shortages some described as "severe."

Hoarding drove prices higher still and depleted supply sources more quickly; but you do what you gotta do to make sure your business will survive.

Manufacturers reported that THEIR inflation rate on THEIR prices accelerated in April. Of course it did with hoarding in the face of shortages, and with speculators bidding up commods, etc.. (In which case, how is the rate of inflation NOT going to accelerate for consumers in May or whenever those products hit the market?) Manufacturers also reported there were no signs of that acceleration backing off.

Naturally, in that kind of environment, lead times for getting materials increased.

In spite of the hoarding efforts and because of the shortages and the transportation slowdowns, inventories of finished goods, ready to go to market, fell. They did not fall because people bought more, though ...

Consumer demand in April remained strong.

So, the consumer, in order to fill his or her demand, is going to have to pay a lot more a lot quicker to compete with other people wanting the limited supply that will be coming down the pipe now that inventories of finished goods are getting thin. In a situation of falling supply from manufacturers, it's more possible to raise prices because demand needs to fall to match the diminished supply anyway. The market will find a new equilibrium via pricing.

When there was enough supply for 200-million people, but is now only enough for 150-million, prices can easily rise until 50-million people drop out of the market due to inflation, especially when those price increases are being pressured by rising costs for producers. If they don't have enough to sell to meet demand, they might as well raise prices until demand falls to match with what they have to sell. If it were only a situation of supply falling for consumers because a competitor went out of business, other manufacturers might hold their prices at the same level to compete for market share; but when their own costs are soaring and their own supplies are getting tight, that isn't likely to happen.

Then you have to add to that, the increased costs and renewed delays in shipping as high fuel prices pour through, putting some truckers out of business if they cannot raise the price of their services enough to compensate. The producer faces all of that getting materials in, and then the retailer/dealer faces all of that getting products shipped to their stores.

S&P's Global US Manufacturing PMI reported,

Firms continued to pass higher material and staff costs on to clients in April, as the rate of charge inflation accelerated. The increase in selling prices was the fastest since last October.

That doesn't sound like inflation has peaked to me. Those products will be hitting shelves in May or in months ahead. Therefore, since that is what was reported on the producer side for April, May's consumer price index rate of change is likely to come in hotter. If not May, then the months ahead.

Oh, by the way, here is what that so-called indication of a top in inflation looks like in the producer side:

Can you see it? First, you have to break your neck to look up that high. Second, the turn is so insignificant, you still may need binoculars to pick it out. Third, the only downturn is in the year-on-year figure where it is now matching up against months in the past that started seeing some significant inflation. Month-on-month was still an additional rise in prices.

That was the breath of fresh air. I think of it like one of those parched days where for just a fleeting second you get a slight breeze on your forehead -- enough to hope it means more is coming, but then the air is dead again and the temperatures keep climbing ... like this blue line:

Turns out goods are still going up. It was services (a larger sector of the US economy than manufacturing now that we moved manufacturing to China) that went down. And see that dip in goods (blue line) that happened going into 2022? That hardly turned out to be a top, proving one little dip is far from an assurance of a top. Look at services again (green line), and you see several little dips along the upward line that were false summits.

And here's where we were last time I showed the previous graph (the one with only one line), exactly one month ago:

As you can see, we still made a pretty good additional reach.

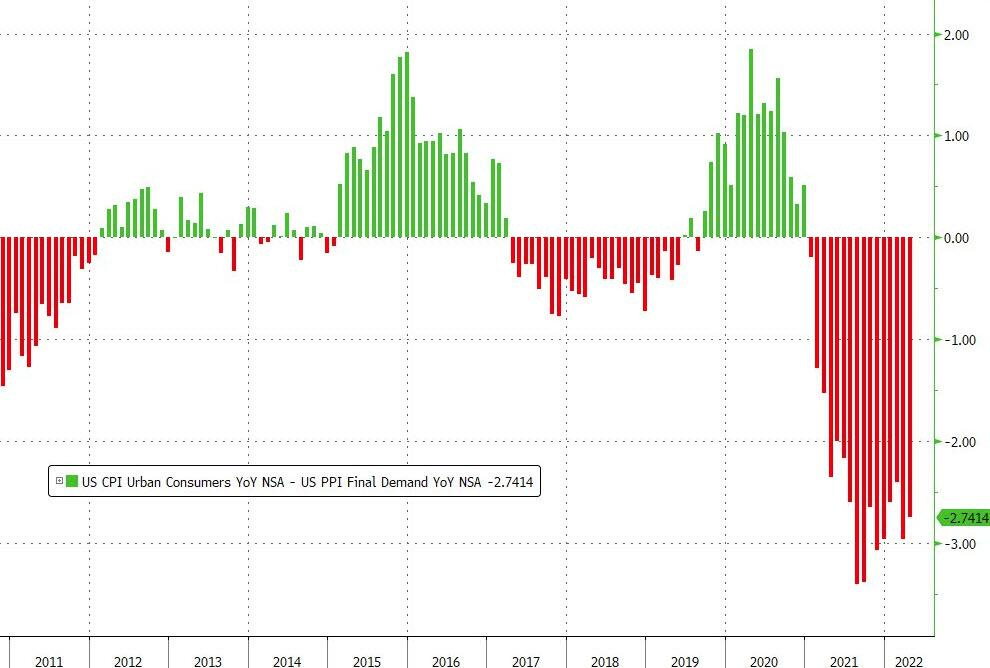

A month ago, I also showed you this graph:

That's the difference between how much prices changed on the producer side and how much on the consumer side. A move down in the red, means producers are taking it on the lam -- are not passing along, on the run, their full cost increases to consumers. That's a net negative for producers that really pressures a move to the green. As you can see in the latest graph, things took a turn for the worst:

March got revised downward and April is worse than January or February. So, evidence of a turn is more a hope than a fact so far. The amount of red that would like to be passed along to consumers went back to growing. With producer prices rising at the 11% level and consumers down at 8.5% there is clearly some pressure building between the two where the internal price friction is heating up. Part of that is retailers absorbing the costs. Part of that is producers absorbing costs. All of that wants to be passed along to the consumer.

Think of it as the hot wind far south is blowing your way at 45 miles per hour, but the wind where you are is blowing at thirty. Obviously pressure is forming along the way as the hot air compresses that is likely to start moving that hot southern air your way faster in the hours or days ahead.

There are no straight lines to anywhere in economics. Though this rise has been straighter than any we've seen since, at least, the seventies. So, we need to see more than a single month's downtick to say it looks like a top may be forming.

Shown another way, the index value for CPI versus the headline rate change, looks like this, showing the cumulative effect of those percentage changes. As you can see, even that aggregate effect on prices goes up and down. However, it is not subject to the base effect because it is an all-time accumulation of price increases, not a year-on-year or month-on-month comparison:

Supposing the rate of rise (the percentage increase) does slow down. That effects the steepness of the line in this graph, but it can slow and still be rising far faster than the trend from 2007 to 2021; and, as you see, the latest dip from an 8.5% rate to 8.3% can't even be called a waver in the overall price accumulation because the baseline effect is not involved, which is all the last little dip was about.

All of which is to say, the dreamers are resting on a pretty skinny hope when they say, "Ahh, the top is in." And keep in mind all those other effects I've pointed out earlier in this series, such as how slow actual past housing inflation is to start working its way into CPI numbers. There is, after all, a little disparity right now between real market figures and what CPI is showing: (Which line does your pocketbook pay?)

Here's your dollar's purchasing power. It doesn't really look to me like its fall is slowing:

Get out your magnifying glass and prove to me there is a sign of a turnaround at the end there. Scant hope.

As can be imagined, a lot of the fundamental supply issues mentioned above were originating from China but when China finally opens back up from its austere Covid lockdowns, don't expect that means the supply problem gets better. When things move in lurches, they jam up elsewhere. As all those ships now backed up around China start to try to stream though Chinese ports and then off to other national ports we'll see a lot of logjams further downstream because the next ports in line will by no means be up to handling the onrush. This is a backup that, at its very shortest, will last throughout the summer because it is likely to become worse here for awhile if it gets better in China. It's not easy getting such complex flows smoothed back out once they have become so formidably screwed up.

A finger to the dessert wind

Besides looking up the pipeline to see how much supply is coming down it and with what pricing changes in store, we can raise a finger to the arid wind to feel the direction of some of the major trends.

First, we have the macro trend, which is years of chronic underinvestment in commodities production, partially because they are unpopular because they pollute the earth, so we regulate them tightly and partially because financiers have become obsessed with backing green projects, and largely because shareholders have become greedy and short-term in their thinking and want all the profits in their pockets. As a result, we are not robust with reserve capacity to carry us through times when trade wars and then lockdowns and then sanctions cut off external supplies from countries where we didn't have to see the pollution. We have little to no resiliency because we've crimped mining, drilling, and other resource supplies in the US.

In the same way, we've reduced manufacturing in the US. Both the resource limitations and the production limitations will take years to restore. It's kind of like when the government issues edicts to switch to entirely electrical transportation in a few years while it is reducing relatively clean hydro power and immediately dirty coal and diesel generation and long-term risky nuclear power, and we're doing that when half the US is facing the prospect of electrical shortages already, even without all those EVs.

We delude ourselves by just pretending that obvious coming severe electrical shortage will resolve itself, but our denial will be forced to break as an undersupplied electrical grid burns out under the much heavier load, and that's only three years away based on EV targets! It takes a lot longer than that to improve and build new dams, but we're tearing down old dams! We're intentionally making the upcoming shortages worse! The two goals cannot be reconciled. We tear down electrical supply systems that we deem not clean while claiming we must convert entirely to electric vehicles because they claim they are clean. Makes zero sense. How can EVs be clean if we cannot run with without dirty electricity?

More windmills and solar panels? Sure, but where? Cover the mountain sides to make sure everything under the solar panels dies and to turn our beautiful mountains into giant machines? Is anyone running the numbers on what those toxic solar panels do to landfills when they reach their expiration date? That's an improvement by switching to electrical vehicles? Where is the lithium coming from for all the extra batteries when we hate to expand mining? What is the true environmental impact of all those "clean" machines?

Enjoy the years of brownouts and blackouts that are definitely coming as we switch to EVs! Then think of what it means for the inflation of electrical prices if we're going to build up grid capacity fast enough to start accommodating that by 2025 when manufacturers are aiming for all-electrical or mostly-electrical fleets.

As you can see, we have grossly underinvested in North America for the size of our economies and the changes we are planning:

I'm not saying we can go without regulations that keep us from creating rivers that burn, as we did in the sixties, but the restrictions those regs place on our ability to be self-reliant in times like these are real. We have entirely brought the current shortages of almost everything -- including all forms of energy -- upon ourselves through regulations and years of underinvestment and then trade wars and then Covid lockdowns and then war foisted upon us and then the sanctions that we chose to deploy for battle. We're nowhere near as robust as we once were for handling all of that.

Right now there is plenty of cash flow in commodity production to boost output, but that still takes time -- time that we don't have with inflation already wilting our economy and withering our personal wealth. Over time, these problems can be fixed, but that won't help us this year and probably not next. So, that means prices will keep rising faster than we are used to.

As we all know and as the following graph affirms, most US corporations have not done their manufacturing domestically for many years:

I won't go further down the macro road because I want to focus on the short-term matters that will be pushing inflation higher right away, but I just wanted to give that reminder that, behind all the current flurry, we have some longterm changes in our economic climate that are not conducive to our plans or our lifestyle dreams. We might have begun to put in a slight turn in US production (bottom of the graph) due to trade wars and then Covid lockdowns forcing us to, but it is very slight, and we clearly have a long way to go if we are going to produce anywhere near what we like to consume. So, with international trade badly broken, we'll have tight supply and higher prices for a long time, and there is nothing the Fed can do about that.

The price of flaming backdrafts

There is also this little kink: The Fed is raising interest rates to cool the already cooling economy, but raising interest rates cools the economy in part by making everything more expensive. Anywhere businesses are using lines of credit, their costs rise, so their prices rise. Anywhere consumers are using lines of credit, their costs rise even if the prices don't rise. So, raising interest cools the economy, but it does it by making you, at least, in the short term, poorer until it breaks the economy, and THEN prices fall. In short, the Fed breaks the back of inflation by breaking the economy.

Thus, we see the housing market cooling, not because there are fewer people wanting houses, but because the cost of housing -- already having inflated massively due to demand short supply -- is now rising due to interest rates. Prices have stopped rising, and have even backed off a little, but payments have risen anyway due to interest.

That is a form of inflation for anyone buying on payments because the cost of "money" goes up.

At some point, the Fed raises rates enough to crush the economy, and that finally brings down price inflation. That is basically what its interest hikes are intended to do. It's how they do what they do to kill inflation. Just crush the economy until it stops. So, a soft landing from this height? Please! There is too much to crush for that to be possible!

Therefore, one had best be out of debt that has variable interest as much as possible because this road out of inflation eats you alive if you have any debt with adjustable interest rates. The cost in the eighties of killing the inflation that began in the seventies and was allowed to run too long was raising the interest on your mortgage to around 16%.

The feckless Fed is fried

So, yeah, the only way the Fed can crush inflation now that it has let it run out of control is to crush the economy, which is going to cost you dearly. I'm sorry, but there is no easy path out of the corner the Fed has painted all of us into. There are many reasons the Fed cannot battle down inflation without destroying the moribund economy; yet, it has to try because everyone will blame it for all that it has already done to fuel inflation with massive money supply. And, what the Fed doesn't do, stifling inflation will do to you anyway.

With about a current 8.3% inflation rate (if you give the Bureau of Lying Statistics credit where credit is not due), the 10YR treasury, at a yield of 2.8% at the moment of this writing, real rate of -5.5% that you're losing by holding a bond. I think that indicates the Fed will have to get bonds to price a lot higher before they start seriously beating down inflation. After all, it's hard to see negative real interest rates as being anything but stimulative. What kind of wonderland economy have we entered if the neutral rate for the real "price of money" is negative, meaning you effectively have to pay people to hold it for you?

Given how much stocks are falling in the face of rising bond yields and numerous other troubles, can you imagine how badly they would fall if 10YR simply reprices to 8.3% -- now that the Fed has released it to market forces by no longer hosing up new issuances of government treasuries -- just to balance inflation at no loss for those banking their money. Neither stocks nor bond funds could handle that because bond funds are still stuffed with too many lower-paying bonds that would start to smell like a fish in the hot sun.

On the flip side of that, ask yourself when you hear market delusionals saying inflation has peaked so the Fed can back off from its tightening fairly soon, how the Fed is going to staunch inflation with its key rate priced far below the inflation rate? Yet, they all seem to think the Fed can kill inflation by hitting a Fed Funds Rate to around 2.5% to 3% by the end of the year.

As a reminder, adjusted for inflation, this is the real interest hole we have to crawl back out of just to get bonds to where they pay you nothing to sit on your money for years:

It's a long hike just to get back to zero. So much for any hope of safe retirement investments.

Now here's the thing: Without the Fed holding bonds facedown with an armlock, as it did for the past two years, bonds naturally want to float back up just to get where they're no longer underwater. Investors naturally seek real gains, and pensioners would not like to lose more than 5% of their retirement each year just to inflation so their tendency to hold out for something positive results in fewer interested buyers for all those treasuries that the Fed will soon start to roll off its balance sheet, which the Fed has indicated will begin after its next FOMC meeting. I think that deeply suppressed yield is going to rise faster than the Fed believes in order to attract enough buyers at this level bond-eating inflation ... although, dollar-denominated bonds are benefiting by being the best-horse-in-the-glue factory because losing 5.5% a year to inflation is a lot better than losing 20% or more in stocks PLUS the loss to inflation on the value that remains.

David Stockman sums the situation up this way:

Within a few months, the Fed will be dumping $95 billion of supply per month into the bond pits—-virtually the opposite of the $120 billion per month supply removal that had prevailed after March 2020. At the same time, Federal borrowing requirements will remain massive because the structural deficit has become deeply embedded in policy.... Thus, for the LTM period ending in March the Federal deficit totaled $1.6 trillion and we see no sign that it’s going lower any time soon.

Yet, the Fed pretends it can do that. It couldn't even do it in 2018 at half the roll-off and almost zero inflation! I promised you the Fed would find itself stuck in a situation where it had to do quantitative tightening much faster than anyone was expecting. Now, here we are with the Fed promising to roll off almost twice as many bonds each month as the $50 billion it rolled off at top speed during its previous failed attempt at QT, which would have become a catastrophe if the Fed had not aborted that much slower plan. Even then, the Fed wound up in a repo crisis where it had to go right back to replacing every penny it had rolled off and a whole lot more.

Even before COVID, the Fed was adding back in a revolving $150 billion or so in "not-QE," "overnight" loans to banks to make them flush, meaning they were saying it wasn't QE because it was supposedly temporary; but three months into doing it, the amount being rolled over from one night to the next and then one week to the next and finally one month to the next had done nothing but grow in size. The problem only abated when the Fed actually went back to full longterm QE due to all the Covid-lockdown, save-us-from-our-stupid-selves programs as we shut off our economy and pretended that wouldn't cause its own longterm human suffering.

So, as Papa Powell tells you he believes he can bring his federal jumbo jet in for a safe inverted landing, ask yourself how all that debt he's planning to roll off, as it is forced to rise in interest in order to find enough buyers, is not going to create massive interest increases on the tops of businesses and individuals and government that will sink us deeper into the recession we have already dipped into because many interest rates are pegged to government bonds, and all loans have to compete with government bonds for investor funds? When you hear people claiming the recessionary plunge in Q1 was an anomaly that will fade, ask, "How?" The only anomaly will be if we rise out of that recessionary level for a single quarter because that will be nothing but a hiccup with a sock stuffed in its mouth as soon as the Fed starts QT.

As I say, the one saving grace the Fed can hope for is that some of the other major central banks in the world will be tightening, too, so money may flee those markets for a dollar haven. (All of which is also why the dollar is not as imperiled right now as many Fed haters are fantasizing, especially since the yuan is doing poorly right now, and the ruble only looks good because it is not even on the international market, so experiencing no real trading pressures. It's become an almost closed system.)

Fed economists mysteriously believe all of that QT they have to do will only raise interest one percentage point by the time it is done. I think they're insane. If they even make it as far as trying to double the introductory QT to the full $95 billion they plan for this fall, look for all hell to break loose. Remember what happened in 2018 when they simply made the final hike in their unwind speed from $40 billion in bonds per month to $50 billion? The market immediately started wobbling and pitching in October and then went off the rails in December. So, how on earth, with far more outstanding debt all over the nation, will they manage to double their balance-sheet reduction from $47.5 billion per month to $95 billion?

That is the most absurd financial fantasy imaginable.

As Stockman summarizes,

What that adds up to is the return of the bond vigilantes—a revival of the old “crowding-out†syndrome as the bond pits struggle to fund $3.2 trillion of government debt paper per annum with no helping hand from the Fed’s printing press. In that context, of course, it will be business and home mortgage borrowers who will get the short-end of the stick.

Remember, Gramma Yellen told you that full QT in 2018 would be as boring as watching paint dry, and Papa Powell told you it would continue indefinitely on autopilot, as if the Fed did not even need to give it another thought as it continued in the years ahead until the Fed approached its target. Now he's going to land a jumbo jet twice as big as that in terms of how much QT the Fed will be doing ... with the yield curve already having inverted to signal recession ... and recession already in the air on the quarterly GDP gauge as a heavy downdraft on approach?

Yeah, that'll be soft!

You might have believed the Fed heads when they told you they could bring their plane down on autopilot and that watching them do it would be boring the first time around because "Fool me once, shame on you," but you better think twice when they tell you they can handle twice as steep of a glide path, and it will be a "soft landing" because "Fool me twice, shame on me."

Buttercup gonna melt in the sun!